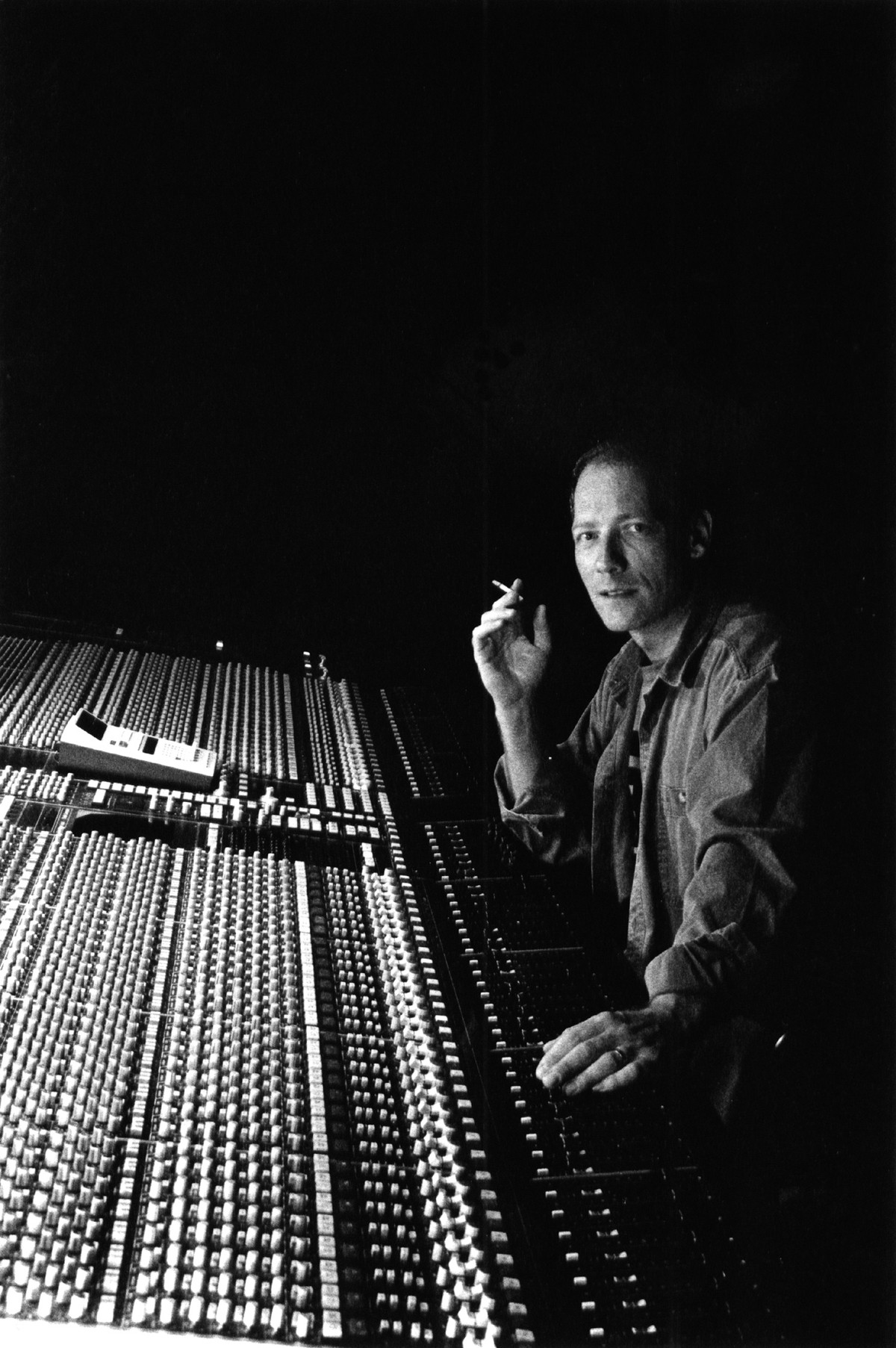

We interviewed Phill Brown in issue number [#12] of Tape Op. Over the years he's worked with some of the greatest artists ever, like Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Robert Palmer, Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, Harry Nilsson, Roxy Music, Stomu Yamash'ta, John Martyn, Little Feat, Atomic Rooster, and Talk Talk. This is another excerpt from his (still!) unpublished book, Are We Still Rolling? Last issue: Phill began doing two albums at once. –LC

Stomu sessions were intense and became more difficult as the days progressed. This was mainly due to the combination of technical requirements, the number of producers and musicians, the use of large amounts of cocaine by almost all involved and the clash of various musical egos. While Steve, Al and Brother James were quiet and relaxed and just "went with the flow", Mike, Paul and Stomu displayed determined and temperamental personalities. From the moment the session started I would be required to work at maximum pace, both physically and mentally, while I looked after 32 microphone and line inputs and attended to the requirements of six musicians and five producers and operated the desk and tape machines. Robert Ash was an excellent asset on these sessions and followed my every move, while keeping an attentive eye on the tape machines and making sure no microphone was accidentally moved by a musician. By contrast, mixing in Studio 2 for Rock Follies was much easier to handle and the daytime sessions became a break from the intense stress of the nights in Studio 1. Robert had opted to join me on my sessions in Studio 2 and now logged the various takes of Rock Follies mixes during the day.

On Stomu's project, Robert and I were pushing the equipment and our concentration to the limit. Although the finished album was planned to sound as a more or less continuous piece, it would be made up of 14 different sections, or songs. The usual procedure was to choose one and play it repeatedly until we had a master. The music was spacious, atmospheric and gentle. The delicate fade-in of instruments over a backdrop of Moog synthesizer would permeate Studio 1 for hour after hour as we floated through our projected "space".

One night we were working on the first six minute section of side one. We had recorded a couple of run-throughs and were now on take three. It started off with wind, intergalactic sounds and a haunting discordant percussion sound from Stomu, before building with piano, bass and drums. This take unfortunately broke down before the last chorus section. There was easily enough tape left for one more version of this 6- minute piece and I left the machine in record and said, "Okay, we're still rolling. Take 4". The Moog drifted in with the wind and we were off again. I looked down into the studio and nine guys would be playing, heads bowed. I would look up to the far wall and see the lunar module disconnecting from the mother ship and the preparations for a Moon landing. The version of the piece they were playing had a fluid, ethereal quality from beginning to end.

As it reached what should have been the end, Klaus unexpectedly went into the next track, "Crossing the Line". This was a beautiful track and became my favorite song of the album, but right now, we had a problem. Robert and I immediately found ourselves at the beginning of a five minute song with only about two minutes of tape left. I felt reluctant to stop them, for two reasons. Firstly I didn't want a technical problem to stop or interrupt this excellent atmosphere, and secondly this was a heavy bunch of musicians and the thought of having to say down the talk-back system, "Sorry guys, we ran out of tape" was horrendous. I moved into "live mobile recording" mode and realized we could use the other multi- track machine, a 16-track. Luckily we were only recording to 18 tracks on the 24-track machine. Two of the 18 were recording the signal from our ambient mics, which I thought, if pushed, we could probably manage without.

We loaded up the 16-track machine with new tape and got ready. Due to the way the Dolby was wired up, the signal could be sent either to the 16- track or to the 24-track machine, but not to both at once, so it would be necessary to switch between them on the fly. I had never needed to do this before and did not know if it would work at all or, if it did work, whether or...