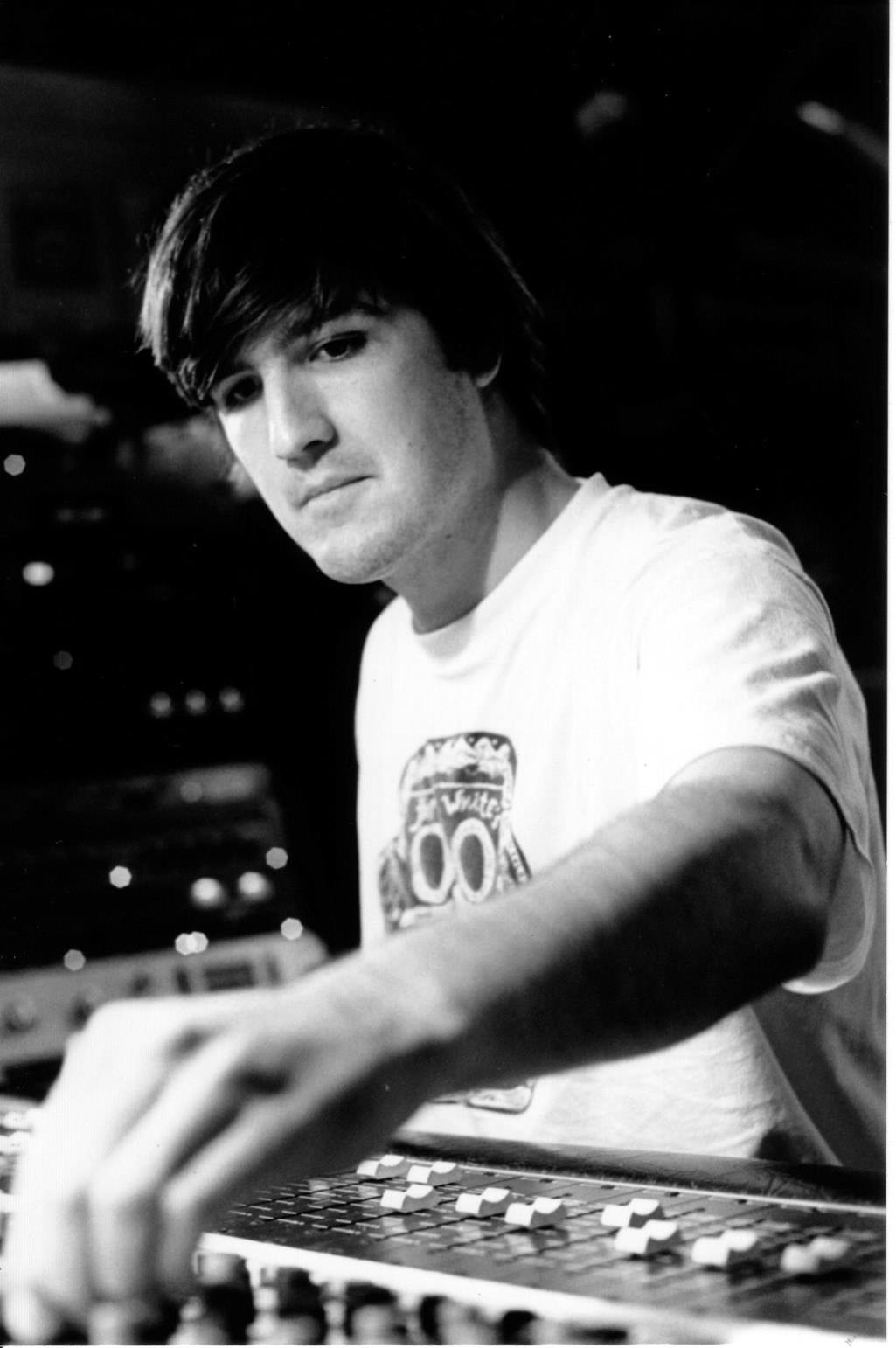

In his solo projects and work with his group Mount Analog, Tucker Martine uses collages of tunes from several genres, as well as electronic soundwashes, field recordings, and fragments from diverse musical domains. He mixes pre-recorded kids clamoring, engine squeals, truckstop jukebox with improvised passages as well as material recorded on stage on the fly, then digitally reconstituted and fed back into the live mix. In this way, he plays his samplers and processors, converting the recording studio into an expansive musical instrument. The result is a shifting, woven, wafting aural cinema of acoustic and electronic sound. In addition, he has become one of the most in-demand producers and engineers among Seattle's more idiosyncratic soundsters, from jazz pioneers to songwriters. He has worked at his Flora Street Studio on projects by Bill Frisell, Land of the Loops, Sanford Arms, Farmer Not So John, Chris Eckman, Danny Barnes, Robin Holcomb and many others. He has also performed and recorded with Sam Rivers, Julian Priester, Wayne Horvitz, Lori Carson and others. The son of a Nashville songwriter who has written for folks like Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Reba McEntire, the soft spoken Martine has a clear grasp on what it means to make interesting records in our contemporary times.

Do you remember what it was that made you want to make records?

It was a funny transition when I started doing it for a living because I was really just accumulating some equipment so that I could mess around and make stuff for myself. I was just fascinated with all the possibilities. Then over time, while figuring out recording by myself and at the same time trying to decide what I wanted to do for a living, it just started overlapping. People I knew were saying, "Well you should record us." So you do it and ask for a little bit of money just to cover your costs, then as time goes on you ask for a bit more until one day, you're doing it. Any money I made went right back into the studio, then after a year or so, you see how it's grown and you have a little legit facility.

Did you go to school for it at all?

I took some courses at this place in Boulder, CO called the Naropa Institute, which is like a Buddhist college. Allen Ginsberg and Harry Smith and William Burroughs, and guys like this were teaching there.

Wild! Were they any of your teachers?

No. But I did spend some time with Harry Smith. He always intrigued me but I didn't know much about him at the time. Since then, I've found out and now I have more to say to him but he's gone. I did take a recording class there. It was a small 8-track studio and a bunch of weirdos teaching this stuff. They weren't really trying to show you how to record instruments as much as they were showing you how to make tape loops and tricks like changing tape speeds and running it backwards. Our assignments would be to make musique concrete pieces or collages, playing for the class and critiquing each other.

So you got into it from an experimental or documentary angle rather than listening to music and saying, "I want to record albums."

I was into music, but when I graduated high school all I knew was that I wanted to play drums. As much as I knew it was a long shot to do that, I thought that that's what I was going to do and it revealed itself to me in this way. I find that I am playing on some of the projects I record and others that I do not record, but recording is what puts food on the table. [laughter] But it's a blast and it's not a compromise. It's what I love doing. It's just as creative if not more. I'm being exposed to different people's ideas and approaches.

So how did you make the transition from wanting to play drums to wanting to record, or has recording just taken a priority but you'd really rather make a living playing drums?

Well, at a certain point I was getting a lot of calls to record people but only the occasional call to play drums. I wanted to get good at recording people and the best way is by doing it a lot, so I took anything that came my way. I've been fortunate to be associated with some pretty good people. It's a perfect way of learning something, by doing it rather than sitting in a classroom where they say, "When you're actually doing it, here's how you should react."

There's going to be a knob called trim, gain, mic pre... turn that.

Here's what to do when the artist throws a tantrum.

They don't teach that in school, though that's a problem.

They don't. Making a good recording with someone has as much to do with compatible personalities as technical know-how.

I know you are using a 2" 16-track now. Do you still have your old 4- track?

No, but I've had people bring in their cassette 8-tracks lately. They have a really cool sound. I guess those Latin Playboy records were all started on cassette multitrack. In their shining moments, I can't think of a cooler sounding record.

I told you that story about recording Sun City Girls on cassette 4- track and mixing it through a Neve? That's probably what they are doing. Recording on these cassette formats and mixing through million dollar boards.

Or dumping them to a Studer 2".

It's a different sound.

Yeah, it will sound a lot different than if they started with the 2".

What type of music were you into early on?

I remember Charles Hayward was really inspirational, because he was a drummer. He was making these records with unusual textures. Electric Miles Davis stuff too. I was also inspired by Daniel Lanois [Tape Op #37] sensibilities and Brian Eno [Tape Op #85], the way they would use the studio as an instrument, definitely opened my eyes a lot. Where the sound you get is integral to the music rather than peripheral.

What possesses you to travel around the globe, record sounds and then come home and put it in a form that's presentable on disc?

The Moroccan disc was because I was entranced and enamored by the Gnawan music and I felt like I had to know where this music comes from, what kind of environment does this happen in? What does the air feel like? So I had to check it out. I had a pro Walkman D6 and an Audio Technica stereo mic. I went there to collect sounds because I knew that even the everyday sounds were going to be interesting, but there was no intent on making a record. I met a guy playing the guimbri on the beach. We started talking and I asked him if he'd play me a song. It was amazing so I asked him if I could record it. So we did. He then communicated to me that I should meet him at noon the next day. I did that and found seven of them rearing and ready to go. They were there with the ritual garb and made an elaborate meal and passing around the kif. They would point at the mic indicating that I should get it out. I found myself in this situation where I basically spent the next six days there recording. A few days into it they started negotiating and talking about money. At this time they also pulled out a photo of them playing with Pharaoh Sanders. I then started to piece it together that these guys had just been paid a decent chunk of change and thought I could do the same. After I explained that I didn't have an Island Records budget they were cool and we agreed of something like $700 and everyone was happy. I had my cassette and when I got back, I just put some tapes together and gave it to friends and everybody was talking about it way more than I expected. Someone offered to put it out so I had to put it together. Field recording is appealing because it cuts to the core of why I love recording. In order to get the good stuff you have to always be ready to have the tape rolling immediately when you encounter the sounds converging in the right way. You don't get another take or separate tracks or any of that business. But when you get it, it's magical. It's already mixed too!

I used a bit of tape from your Morocco trip in the Climax Golden Twins Locations CD, and we edited the Mali recordings together and other tapes make their way into Mount Analog. In addition, Mount Analog, the CD, is a perfect reflection of the type of personality you are. At times it's a bit dark like a Lynch movie, but depending on the listener's frame of mind, it could make you relaxed, which is a lot like the kind of person you are. I also feel it is like a mirror to you rather than a collective thing with other musicians.

Definitely the first record is that way. It was me in my basement with all my knobs and wires just stumbling around until I found something interesting and developing that. Most of those pieces where created for Butoh dance, which I was really interested in at the time. Butoh is slow and dark and a little bit humorous and I think that is reflected in a lot of those pieces, but there is also something serene about it. Yes, I brought a few friends in to provide textures that I couldn't create, people that are proficient on various melodic instruments.

Do you think that Mount Analog was a labor of love, like Pint Sized Spartacus is for me, where you were able to accomplish things that you always wanted to accomplish but couldn't with a group because they didn't want to get that experimental?

Yeah, I think it was the result of the frustration to find the perfect bandmates and not wanting to wait around for that to happen. Finally, I didn't have the excuse of not having the equipment anymore and I had plenty of ideas. I was stockpiling sounds on various types of recorders. So what happens if I take this into my own hands? At the same time, friends were asking me to do something for these Butoh pieces, so I decide to try it. I didn't sit down with the intention of making a record but when I reviewed the material it seemed like there was a coherent theme, which documented a period, which is different than what I would do now. I love it! That's what I think records are about is documenting the ideas of that time.

Did you employ interesting recording techniques or discover looping or ideas like that on the Mount Analog tapes?

Yeah, I remember feeding effects back into themselves, just hanging on to that point where it's about to get out of hand. Also a lot of processing of sounds to the point where the source becomes unrecognizable.

That's a kind of Eno thing.

Yeah. Maybe you start out with a sound that's not that interesting on its own, but you zero in on the 5 percent of it that is interesting and bring that out... that's fair game.

On the Andrew Drury record you told me about running the drum tracks through an effect and then into an amp and mic'ing that to create a beat box effect.

Certain sounds will trigger an idea. When you get a strong vision for something, you just have to hook it up and try it. At the times when I don't have a strong vision I will try to be more transparent and let things take its course, when working with another artist. I like to keep a lot of those 120 [minute] DATs around. Even when something has the slightest hint of being worthwhile, just run it to DAT for a bit. More often than not, I'll come back to it a month or two later, not even remembering how I arrived at it and say, "Wow, that's amazing! It would be the perfect introduction to this other piece that's coming together." So it's the constant stockpiling of sounds. Maybe I'm producing a band and they are setting up and shit's all set up wrong and it sounds amazing. You ask them to keep doing that for two minutes while you roll some tape. I'm now getting better at logging all my DATs so if I'm working on a project and it needs a certain texture, I can go to the DAT and find it.

You've started working at other studios now, other than your own. In doing that, do you think that has improved your techniques? And another part of the questions would be, are you hearing things that you hadn't heard before or prefer some piece of equipment to other pieces?

It really helps in determining what is and is not you as far as sound quality is concerned. If I used the same mic techniques on the same instrument in a better sounding room and you get an amazing sound, you know that it's not some special magic box. The room is how they get the sound in that case. Sometimes you find the sound is not as cool. The more I work at other studios the more confident I am that the sounds I get are going to translate to the outside world. If you only work at one place, you might know that your room is too bassy so you mix with less bass, but the more I work at other places, the more I understand the subtleties of what frequencies are wanted and which are not. I'm not sure how to put it. I think it's more important to have the proper amount of time to make a recording than it is to having the right equipment.

But have you come across certain pieces of gear that you just have to have?

I have. Otherwise you're just reading magazines that say, "We used a U47 on the vocals and U87 as overheads." What does this mean to someone who has an 8-track and couple SM57s at home? There are definitely valuable tools and a few things that I've fallen in love with.

Like?

Like the 1176 compressor by Universal Audio or the Empirical Labs Distressors. Those are the shit. But I think it's just as challenging to get good sounds in a $1000 per day room as it is a $200 per day room. It's just different parameters to work within.

Do you ever feel compelled to pull the 1176 out and take it with you?

Yes, but I try to find studios that are geared towards the approach that I like to take. I still find myself showing up with not a lot except a few cheap pedals or a tape delay and other things that a studio of that caliber might not have on hand because it's too cheap.

Do you still feel at home in your own studio or do you want to branch out into other places?

I feel at home, when I'm not rushed and I'm working in a situation where the dynamic really gels as far as the people go. Smaller things. I'm comfortable at home, you know three or four people, but for bigger things? The weakest link in my chain right now is not something I can buy and bring in, it's the room. I have a nice 2" 16-track tape machine and a cool sounding Neotek board, enough decent mics and some outboard gear, but none of those things are going to give you 15 or 20-foot ceilings. I had a dream once that we dug into the ground at my studio 30 feet and I finally had all this space and boy was I bummed when I woke up! [laughter]

That's what Zappa did, he just started building bunkers into the ground on his property.

One cool thing at Flora is that I now have a snake upstairs so I have the acoustic options of the living room with the higher ceilings and hardwood floors or the bathroom with the tile or a stair well. So not only do I have the acoustic properties of these rooms but also the extreme isolation. I have an upright piano upstairs too.

Excellent. How about techniques? Let's get into that.

One thing I found lately is that you can get some really good sounds direct. For a long time I was pretty opposed to that except for maybe bass. But with the right sequence of pedals or slap back delay or a SansAmp. You can get sounds that will sit in the mix like it has air around it. It's an artificial air but it can be really cool. You can get textures out of a guitar that you'll never get out of an amp. More on the production end, I like to have people overdub without hearing some of the defining tracks like the rhythm section. I just give them the organ pad to play to. Then I erase all but the best moments of their performance. That's something that's been working with Mount Analog lately. You end up with a really interesting take on things.

What are you listening for when you mix?

Basically trying to create a fascinating world that will draw someone in. Unless it's something like a bluegrass band or a jazz live-to-DAT or something like that, I don't let myself become to pre-occupied with the sounds being too pure because so much of the music that I loved before I knew the first thing about recording is totally impure. Like double tracking vocals or guitars. I look for a lot of depth and balance. I try to find the best way to arrange the sounds on a tape. If that means whipping out all the effects or none at all.

What suggestions do you have for the up and coming?

I would say, let your enthusiasm for it guide you rather than your desire to make a living. If it turns out that you're actually good at it, people will notice that. As long as you are interacting with people that are making music on some level, it's really just a matter of time before you have use for one another. People just need to see that you're doing it and that you're serious about it. The more you do it, the more your sensibilities improve and then people will come to you for what you like to do. And the more you do what you like, the happier you are.