"It feels so good to be back on the road again," reveals a recharged Daniel Lanois, as the tour RV he's been traveling in merges onto highway 403 just outside of his former hometown of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. For the two previous nights, he, vanguard drummer Brian Blade and an assortment of special guests played a pair of triumphantly moving and intimate "homecoming" concerts here.

First and foremost, Daniel Lanois is an artist: a painter, photographer, thinker and storyteller, though he is best known as a musician and producer. He began his journey into music at a young age when he was given an ultimatum by his music teacher: Choose between learning the pedal steel guitar or the accordion. Many moons later, the cosmic, antiquated, weeping instrument that is the pedal steel can be heard on Shine (Anti/Epitaph), a record of a haunting, relaxing and engaging hybrid of psychedelic folk, slow driving pop and instrumental songs. It is his first proper album in a decade.

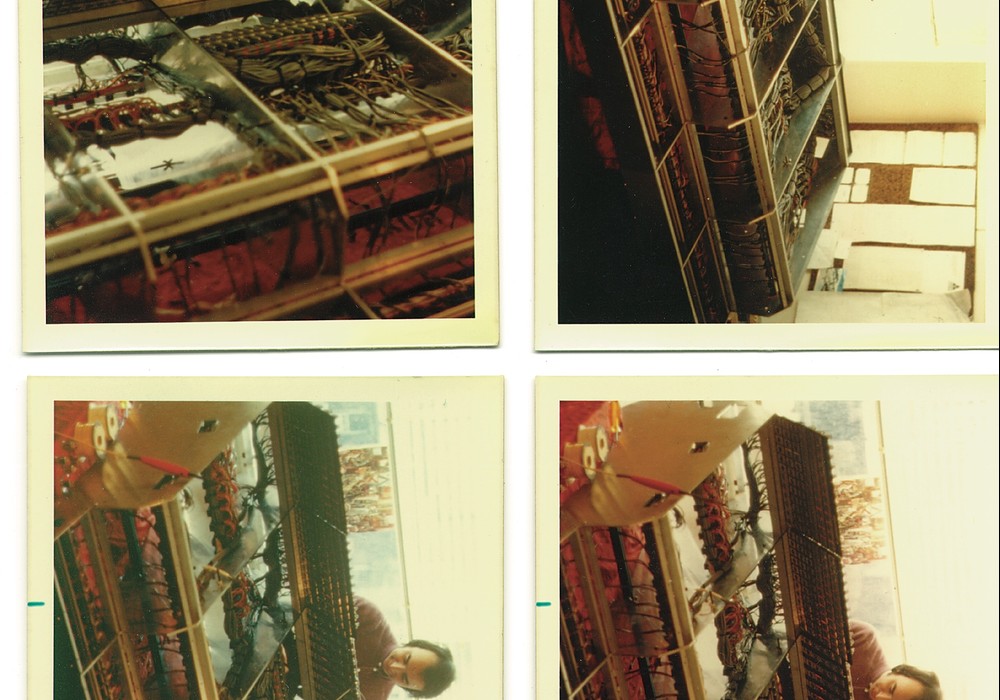

Between and long proceeding those ten years, Daniel Lanois "the producer" has been a conduit and source of ideas — a perceptive human microscope calibrated to aurally identify, display and enhance a fellow artist's talent and methodologies in the studio and beyond. He himself calls his job "soul mining". He is also adept at experimenting with technology — a "sound miner". In fact, it was his curious manipulations of sound in the late '70s that triggered a homing beacon of sorts to Brian Eno [Tape Op #85]. At the time Eno was preparing to delve further into ambient works, hoping to find a recording facility in a modest yet unlikely and distraction-free urban area whereby he could work with the utmost sense of freedom. A project recorded by Lanois happened to cross Eno's path and pique his ears. Everything then pointed towards the autonomous, ultra-blue-collar, back-boned steel-making city of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, a recording studio on Grant Avenue and its owners and operators-collaborators, the brothers Bob and Daniel Lanois. Together Eno and Lanois would break ground, polish listeners' cochlea and inspire countless others with albums such as Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror, Pearl (both with Harold Budd), Ambient 4: On Land, Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks and the Music For Films series.

It was during this period (lasting until the mid-'80s) that Daniel Lanois would exponentially develop his craft as producer, engineer and musician. He would also acquire a further understanding of the concepts of communication — a key ingredient to translating and fortifying talent onto record. Eno, having produced and worked with artists such as Talking Heads and David Bowie, was approached by an Irish band by the name of U2 to produce their next record. Eno, with an increasing interest in other mediums in art at the time, confidently suggested the hungry and inquisitive Lanois to the helm of the project, as he and the band both shared a vision of "building the studio around the band". Lanois was then 32, yet already sporting a modest, impressive resume of production credits.

U2's The Unforgettable Fire propelled Daniel Lanois to a status that would allow him to travel and absorb the world's varying musical cultures. From then on, Lanois would produce further albums by U2, as well as masterpieces (ranging from organic sounding to hi-tech productions) by Peter Gabriel [Tape Op #63] (So, US and engineering the Birdy soundtrack), Bob Dylan (Oh Mercy, Time Out Of Mind), Emmylou Harris (Wrecking Ball), the Neville Brothers (Yellow Moon) and Robbie Robertson, as well as Lanois' own "solo" efforts Acadie and For The Beauty Of Wynona.

There is an arguable misconception that any Daniel Lanois "production" involves a sort of an aural "trademark" or "stamp". Most of these albums are rich and dense with sonic scenery and atmosphere, the kind that evoke nostalgia, and some might also include his talented guitar playing (which is certainly unique). Yet the "stamp", in fact, is the intense, raw, neuron-firing electrical-emotional passion that gets communicated and passed on via musician to Lanois to recording medium to playback device to listener. It is unquantifiable — it can only be felt. And it is up to the listener to have their receptors set to "on" or "off". There is no in-between. Another production tool of his is the ability to identify an amazingly talented musician and invite them to partake in a recording. A Daniel Lanois production, when applicable, will include musicians from varying parts of the globe, who bring a completely different perspective to a certain genre of music, thus taking one's project to a higher level.

To this day Lanois has retained a hard-working attitude and ethic. (Backstage after one show, an old friend and bandmate recounted how after their bar gigs, Lanois would continue practicing the guitar while everyone else partook in ritual partying.) These traits were, no doubt, planted in him from his days of growing up and having to fend for himself financially. The style even shows in his guitar playing — a rugged, native Neil Young-meets-Jimi Hendrix type of assault on the strings — chopping away, hitting notes at every angle and part of his hand possible.

The RV sails towards London, Ontario, the next destination on the Shine tour. Like the famed eccentric piano player Glenn Gould, he occasionally wears a pair of black gloves to protect the hands (or the "gift", as he calls it) from possible unnecessary wear and tear when working out (which he does lightly on and off throughout the day) or simply handling things. At the moment, Lanois occupies the small humble kitchen section of the RV, restocking various items. When speaking, he sometimes personifies things, making references and metaphors to things being akin to kitchens and cooking. His shows, in fact, can be referred to as being kitchen parties, where friends are invited to play and sit in the periphery onstage, much like in the same manner as the old days when his family in his native Quebec would gather in the kitchen and sing songs.

The hour or so drive was an idyllic time for Dan to lay down some thoughts for Tape Op. Even before I can suggest a method in which to minimize the sound of highway traffic and wind in order to capture our voices more clearly, his attentiveness and sharp sense of focus immediately come into play. He picks up the cassette tape recorder and thoroughly examines it like a curious scientist with a new sample. In this case, he looks for the small built-in microphone. Upon discovering it, he decides to hold the recording device himself, placing it in close to me and to himself when it is time for either of us to speak respectively. He comes across as both a mysterious character and an accommodating, warm person.

At times like these, one must always be recording. This is one of Lanois' major virtues. Always record, for the moment that's needed might otherwise slip by forever. A Daniel Lanois recording will likely contain some highly interesting sonics occurring, but the number one ingredient is always passion. (His sonics, however, certainly surpass convention.)

I was wondering about something you said at the SXSW conference — something about how and why a studio can be intimidating to an artist — that the musicians themselves should have ease of access to be able to operate equipment in addition to the engineer/producer.

Well, I think some of the functions in the studio should be regarded to be public functions. Knowing what the arrangement of the song is — that should be made public. The clock positions of your recording system should also be made public. So that the people in the room can educate themselves as the work is progressing. For example, if the guitar player hears a point in the song where he feels he wants to do a repair or have a point to come back to, it's nice for that person to be able to say, "Could we go to number — 2 minutes 37 seconds, please?" and so the engineer knows what he's talking about. With the wonderful advantages of modern day technology, one of the things that has not improved seemingly is exactly that — the communication system. So it has become more elitist, in a sense that the operator of the Pro Tools system has a rack and has a chair and has a job and is getting paid and perhaps the musicians are not included in the process. So we've kind of taken a few steps back in my opinion. I always increase communications systems as much as possible and that's what leads to good work. Some of my best work has been done in places where everyone was speaking the same language.

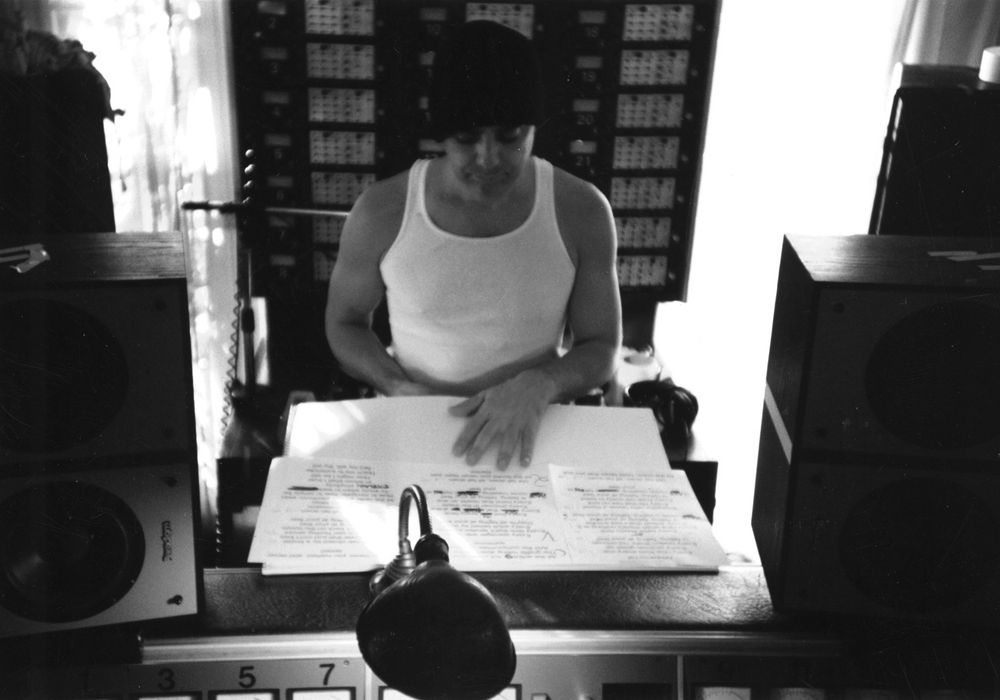

Even back in the day, you and brother Bob began experimenting with the idea of the "open concept" studio — to have the studio built around a band.

I grew up in a conventional studio environment through the 1970s. The usual control room — a piece of glass and musician's room. And I lost interest in that in the late '70s — it became kind of laughable to me. First of all, the amount of time people would spend getting sounds was unappealing to me. Someone would be out there beating on a snare for eight hours — somebody in the control room thinks they're a genius by equalizing it somewhat and I got fed up with it. I thought, "This has nothing to do with music." I also got tired of somebody trying to talk to somebody else in the studio and they're waving their arms and their microphones aren't on and their frustrations would build. I thought [about] why these people don't have problems when they're up on stage, and it's because they're relatively close together and there's no glass, no segregation. So I became fascinated with recording in an open room. I started that in the early 1980s in Hamilton. I used to get use of the old library in Hamilton — it was disused at the time — and they gave me access to it for several months. I recorded a few different bands there and it was great — I treated it more like setting up for a show and we were using more of a P.A. mentality to recording. Harnesses — put that drum over here, bring the microphone over — you know, treating it more like sound reinforcement, like you're doing a show on the Friday and this is Thursday — you gotta get your set-up going. And I found that it increased communication.

Everybody was listening to the same thing. Musicians were hearing their instruments in the room and the engineer would also be hearing the same thing. There's a little bit of a risk involved in the sense that the engineer can't be listening in complete isolation from the player — and you get used to that — you wear cans and what not. I got very musical results out of that system — that's what we did with U2's The Unforgettable Fire essentially. We had a couple of different band rooms giving us a lot of flexibility — the control room became the main...