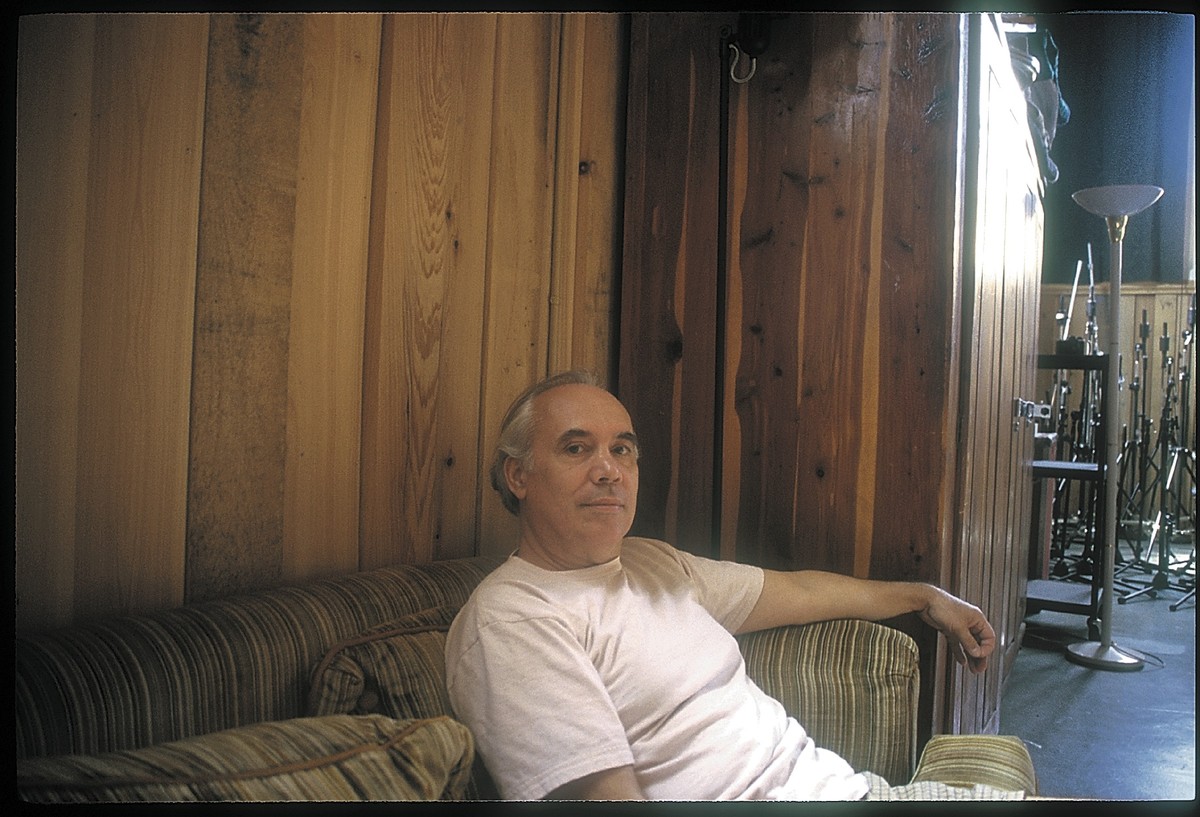

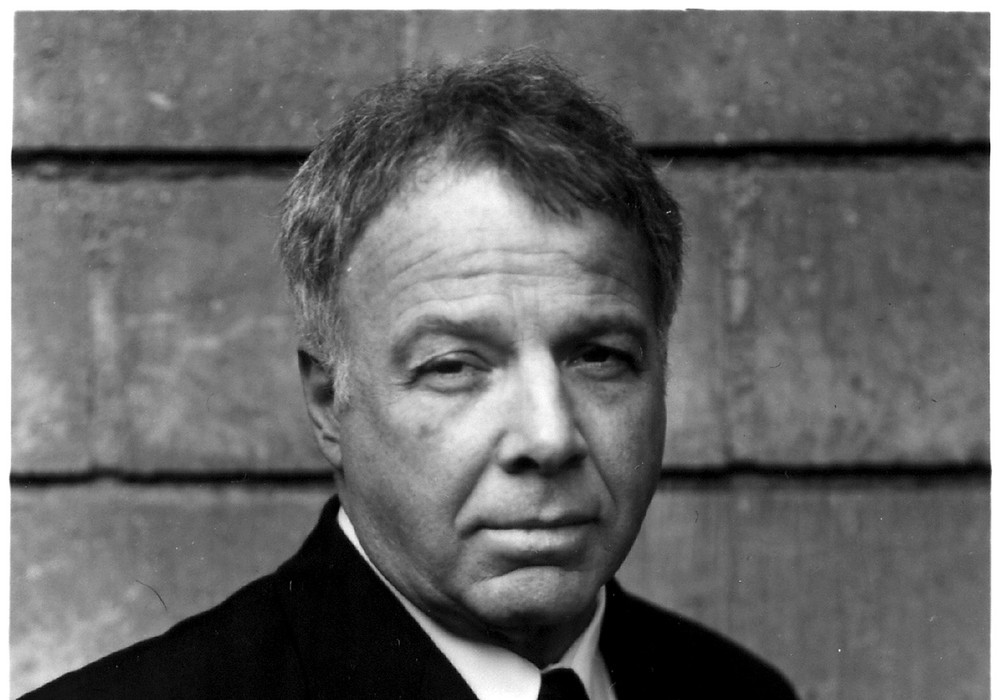

While you may or may not recognize Mark Bingham's name, his career as a musician, engineer, producer and arranger has spanned four decades. From sessions in the '60s watching the Doors record, producing cult bands in the '70s, working briefly with R.E.M. in the early '90s, to his recent opening of a fine studio in New Orleans, he has recorded more styles of music than there are categories. Mark Bingham's career started at Elektra's studios when the label was still setting trends. After leaving Elektra, Bingham and his then- frequent collaborator Mark Hood recorded classics like MX- 80 Sound's Out of the Tunnel and the Bush Tetras' "Too Many Creeps" single. He has worked with experimental jazz giants like saxophonist Kidd Jordan and bassist Mark Dresser. Today, his Piety Street Recording in New Orleans helps to preserve the work of local legends like Aaron Neville and Allen Toussaint.

Bingham formed a rock band while still in high school. "Our band won a band battle, and the judges were Howard Cosell, Cousin Bruce Morrow, and Bill Harvey from Elektra Records, the art director who made those beautiful Nonesuch LP covers. They liked the songs, and I was writing the songs, so they brought me to Elektra, who signed me up as a songwriter. I was 17 and still in high school. It's goofy. I was making all this music that had backwards [parts] in 1966. In the spring of '67, I signed with Elektra's publishing wing. I was still in high school, and they gave me money! Immediately, they were saying, 'Now you've got to learn to write boy-girl songs, me-you songs.' I'm just writing all this crazy stuff in six parts, and I was stupid and stubborn. My boy-girl songs were not so good. It was very stupid. There was one song I wrote [that] the Everly Brothers did. I heard it — I don't think it even got released on a compilation or anything."

While on staff as a songwriter, Mark enjoyed his opportunity to investigate the studio. "They gave me the job of apprentice producer. I did everything from get coffee. I got to see Bruce Botnick, John Haeny, Paul Rothchild and Frazier Mohawk [Barry Friedman] make records. I got to see Doors records getting made, Judy Collins, Rhinoceros. I got to see an awful lot of great music go down as an 18- and 19-year-old. A lot of the sessions I saw were [recorded] live. People were just playing music in a room. I remember this combination of loose and groovy with very meticulous engineering. They had very limited equipment. I remember dealing with the low end of the room. I learned about using omni mics and getting 'em real close on acoustic guitars, over- amping compressors. I also saw how people would put mics up two feet away and get a really beautiful [sound] that never would happen when you stuck mics really close to things. Love's Forever Changes "was around that [time], and that was — and still is — amazing. There's a Nico record called The Marble Index. That's one of the coolest, strange, pop records. Nico and John Cale and that was it. It was all John Cale overdubs. John Cale making this really amazing sound and then the engineers [would] manipulate the sound as it was going down. Frazier Mohawk produced those Nico records.

"You learn how to do stuff with home tape recorders, and sometimes it doesn't translate in big studios. Fortunately for me, I learned early on that you could bring your cassette deck into this big recording studio, plug your guitar into it, put it into record and pause, turn the mic preamps all the way up, and plug that into your amp. That's going to give you this incredible sound just like you got at home that you liked. These professional guys would tell you, 'Oh you can't do that because it's going to do something bad to the equipment.' I, early on, had a bad attitude toward engineers because they were the people that told you you couldn't do things. The good thing about the Elektra engineers was they were willing to try anything. I finally, eventually, understood the concept of turning down, but I've always been into letting 'em play, and figuring out how to sort it out from there. Not going, 'You have to do this because of technology.'

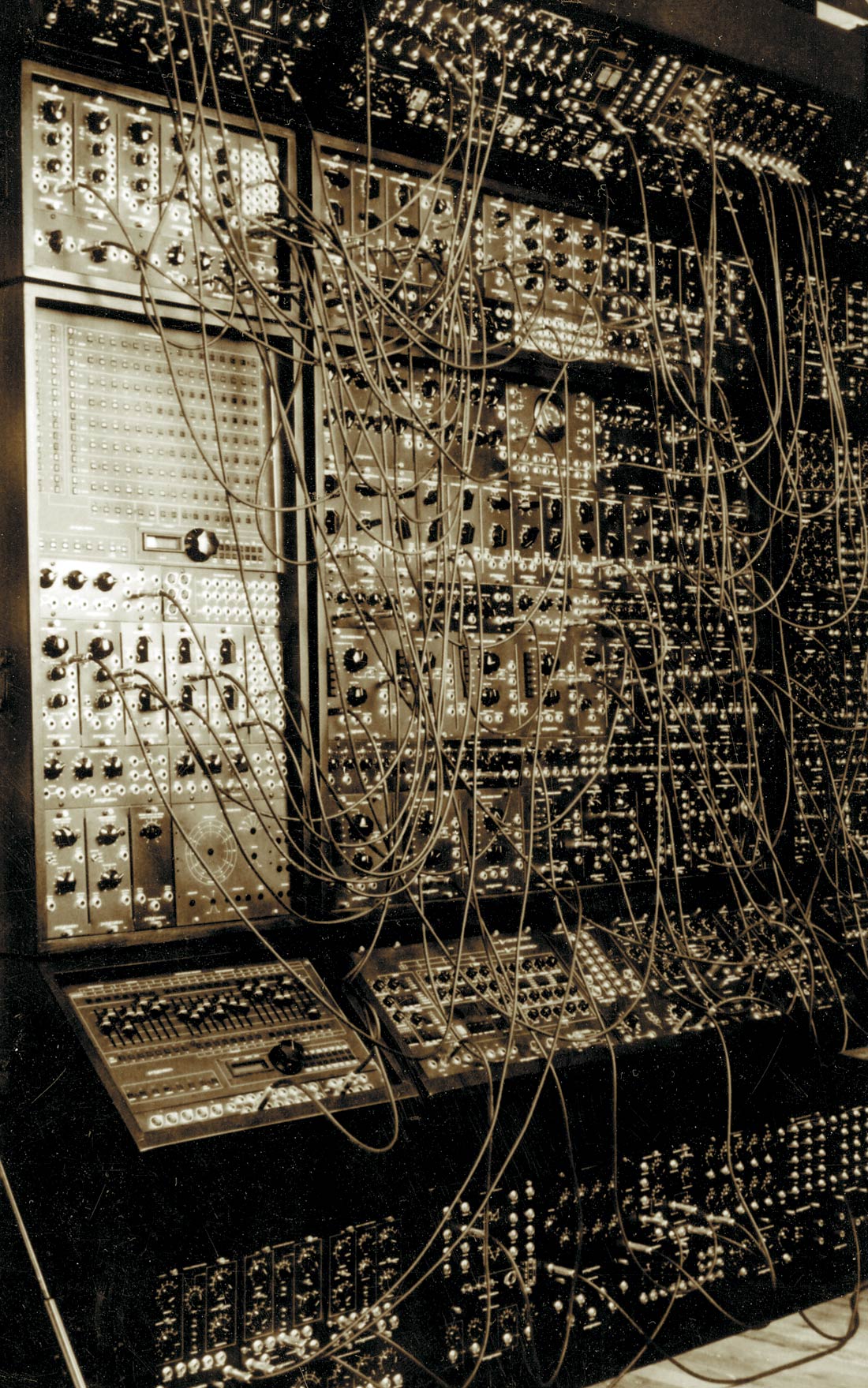

"In L.A., in those days, studios were building their own consoles, like the console at Elektra, I think. I remember that Allen Emig had built a console at Columbia and maybe one at Capitol. He was the Elektra head tech. Engineers were constantly trying to get things to work better, and shit was falling apart left and right, and it was a big ordeal to do audio and get it to sound great. Now, what we've learned is that by having those kinds of equipment where each component did one thing, even if it was difficult and noisy, there's something about it that we liked very much, and that's why all this stuff is...