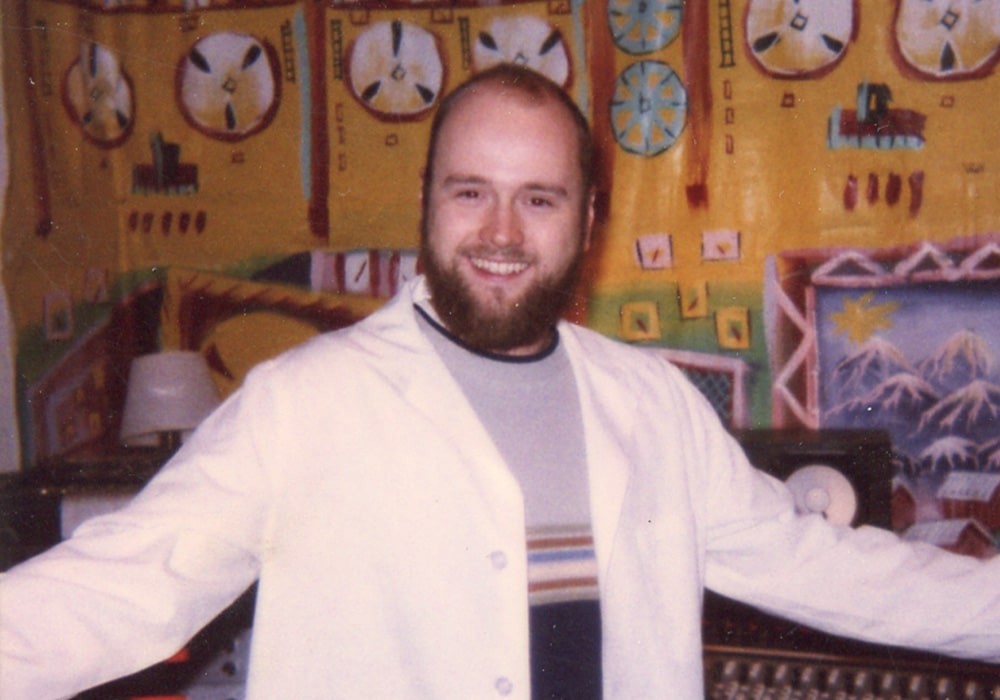

For several years now, the notion of Montreal as a hub of avant- experimental music has grown judiciously in the mindset and record collections of its followers. If you break this down further in the context of a medium to large North American city, it's apparent that most of these sounds emanate from a comparatively small community within Montreal known as "the Mile End." It is here that labels such as Constellation and Alien8 Recordings release music of an uncompromising, intimate and honest nature, inspired, in small part, by the relationship of community, activism, multi-culturalism, the surrounding architecture, train tracks, community run cafes, eateries and music venues. Peel away yet another layer to reveal the fulcrum of this sound, and invariably you'll find the name of Howard Bilerman, Efrim Menuck, or Thierry Amar at the heart of most of the Constellation recordings, as well as other local acts such as Molasses, Hrsta, The Arcade Fire, and The Dears, to name a few. Consequently, The Hotel2Tango has begun to attract people from outside the Mile-End community, from places like Toronto, New York and Boston. Since 2000, all three gentlemen have coaxed intimate mini-symphonies, esoteric art-rock and majestic avant- pop from eager musical hands of peers and friends, from within the ramshackle, humble environs of the Hotel2Tango. Although all three have a deep understanding of recording methodology, their real art is the humility, grace and reverence for capturing the true sound that blood, bone and human hands create without artifice. Their abilities to create an environment of trust, support and willingness to forgo the trappings of modern trickery embolden every project, record and artist they work with.

Before the Hotel2Tango studio existed in its present incarnation with the three of you, you [Efrim] and Thierry worked primarily in an 8-track studio environment with your own gear, and Howard, you had your own studio. What kind of gear were you all working with at the time, and was this an entry into learning about the recording and engineering process?

Thierry: Actually we worked on a Teac 1/4" 4-track before getting the Tascam 8-track. The first Molasses record was done here at the Hotel on the Teac 4-track with a Tascam board and Dynaco speakers, and that was it.

Efrim: We did a lot of tinkering on borrowed 4-track machines for a lot of years, headphones as microphones and obsessive track bouncing. Recorded a pile of little things on 4-track when Thierry and me still lived at the Hotel. Later on we bought a Tascam 8-track and an Allen & Heath 24- channel board from Carter, Labradford's keyboard player. Labradford and godspeed were touring together and Carter had the tape machine and board laying idle in his apartment and offered to sell it to us. We recorded the first Silver Mt. Zion record on that gear, eight tracks feeling like so many sprawling, luxuriant acres at the time.

Howard: I had a 16-track studio in Old Montreal called Mom & Pop Sounds. I had majored in sound in university before that, although I knew how to record bands already. I just enrolled to use the studios for free. They had an 8-track 1/2" studio with lots of beautiful AKG mics. In 2000, when I was looking for a new space, Thierry and Efrim were looking to buy some new gear, so we just brought my gear over here to the hotel.

What kind of console and tape machine does the Hotel use now?

H: Because Molasses electrocuted our MTR 90II, we're now using an MX-80 24-track 2" machine and a Neotek Series II board. Our mixdown deck is an Otari MTR-10 1/4".

People who record bands often differ wildly on the use of compression. I was wondering if you could talk about your take on compression and the different situations where compression can be hindrance or help.

H: I think what makes a recording exciting is dynamic range, and when you over use compression you're getting rid of that dynamic range. I think a lot of people use compression on drums by default... like somehow that's what you are 'supposed' to do. I mean, drums sounds don't come from boxes, they come from players. The best drum sounds I've ever heard are by great players, like Michel Langevin from Voivod who played on Elizabeth Anka Vajagic's record. You don't need to compress those drums because they already sound great.

T: I try to avoid it actually. I mean, it can be useful if you want something to sit in the mix properly, but to me you either use it transparently or you use it creatively. I'm just starting to appreciate compressors for creative means.

H: It's interesting to just run a signal through the compressor, without actually compressing it. It changes things sometimes in a really nice way. The difference between the 1178 and the LA5 and the DBX are like night and day in that regard.

What compressors do you guys have here at the Hotel?

H: Well, there's the two UREI LA5s, two DBX 163Xs, a Langevin Photo-Optical compressor, a UREI 1178, a bunch of Valley-People dynamites, and the RNC 1773 which is really quite versatile — does subtle well and over-the-top really well too.

Do you all tend to record in 15 ips or 30 ips, and aside from the obvious, how do they differ for each of you?

H: Both. There's a pretty huge difference between 15 and 30 ips, in particular how the transients sound. For things like drums, you don't need to EQ in mixdown as much when you record at 30 ips. Having said that, at 30 ips you lose the low end a bit. The flip side to that is that it doesn't get muddy down there, and the...