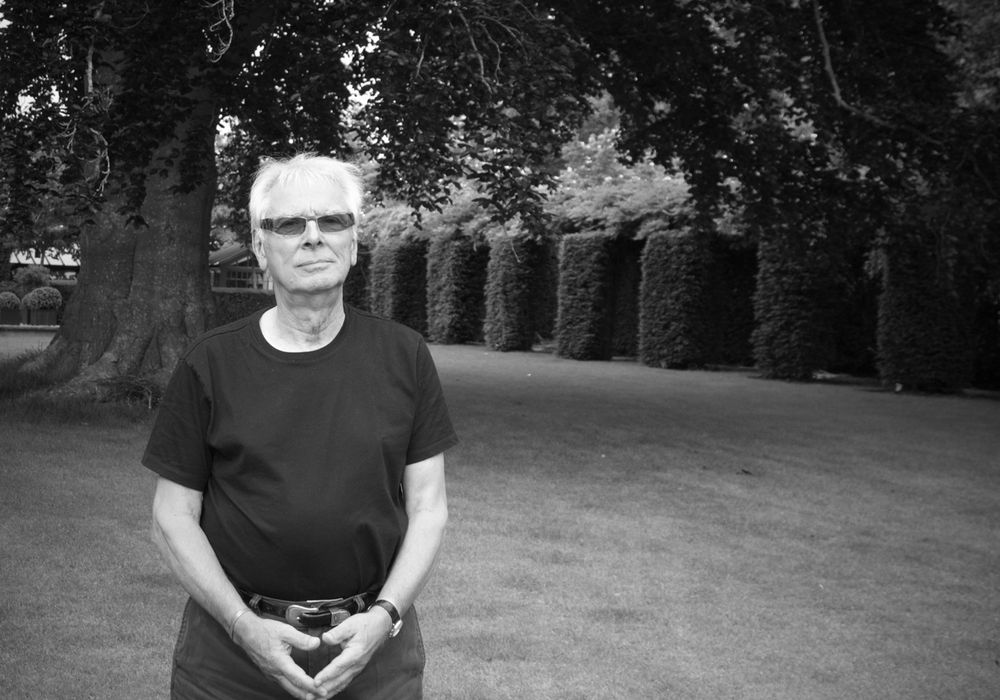

Ethan Johns would be of note to the recording world if only for his familial ties. Being the son of Glyn Johns [Tape Op #109] and the nephew of Andy Johns [Tape Op #39], one might assume his entry into studio work was a shoe-in — but not so, as you'll see below. His current work with artists like Kings of Leon, Ryan Adams and Ray LaMontagne exhibits an organic approach to recording and a playing up of the artist's strengths that may seem at odds with much of the recording world today, but the success of these records also proves that he is helping deliver albums that people enjoy.

This interview was not an easy one to get. One of my best friends, Luther Russell, (see sidebar) was working with Ethan and suggested we all do an interview for Tape Op. On my first visit Ethan basically said no to an interview. His reasoning? What does one have to offer in this situation? Why would anyone want to read about what mics he uses on what and why would that work for anyone else? After hanging out at his Three Crows Studios for hours talking about music and recording, Ethan and I hit it off, especially when he realized I was a studio owner and record maker too. We did an initial interview about the impressive console his father had given him (see the other sidebar) and a bit of his history with recording. When I returned months later I was able to sit down with Ethan for a longer interview, though, unfortunately, Luther was out on tour. I think Ethan's work is some of the finest record production of our times, and his philosophies of recording and music are a breath of fresh air. Many thanks to Luther for starting the ball rolling on this!

How did you get into recording?

Dad gave me a set of keys when I was a kid and said, "These are the keys to the studio."

To the barn?

Yeah. He said, "You wanna learn about recording? Here you are." And that was it!

Because you had pestered him?

No, no. I'd been playing music on one instrument or another since I was a toddler and I'd always wanted to go into the studio, so he let me, "Go figure it out." His idea about teaching was [that] the best way to learn is to just do it. The only way that you get to figure stuff out is by jumping on it and coming up with your own ideas. When I was sixteen I left school and went to work for him full time for a few months, but he had already showed so much by then. I'd been a "t" boy off and on since and had graduated to tape jockey on a few projects, I knew how to wrap a cable but I'd watched him make records all my life. I think the music and the industry had changed on so many levels by 1986 he thought I should learn how to operate an SSL and monitor on telephones if I was going to support myself in music. He basically fired me and kicked me out of the house. "You wanna go do this? Off you go, fucking go get a job." So just like anybody else I would write to every studio in the country for six months every week until somebody finally said, "Okay. Come and make tea for us."

You did gopher work?

Oh yeah. I mean my first job at a recording studio was two months of cleaning out a storage space that had been basically left to rot for ten years.

You're a 4-track head too, right?

Absolutely. That's how I learned. The funny thing is that I very quickly set up my own recording situation. I had an 8-track in the vocal booth that was my little home.

What kind of 8-track?

It was a Tascam cassette 8-track but I'd had a Porta One for few years. I ended up getting a deal as an artist by accident. I sent a reel, a show reel of stuff, to this A&R guy looking for gigs as an engineer. I had such a small amount of stuff, there were a couple of things on the reel that were my own compositions and he called me up and he was interested in those and I was kind of blown away. I know what it's like to be in a relationship with a major label as an artist and I'm sure it formed a lot of my opinions because it was not the best experience for me.

Did you do a solo record?

I did do a solo record.

I've got to find that.

Don't bother.

How so?

Well, it was the first batch of songs I'd ever written. The material was lacking. I can't sing to save my life. I sound like a drowning rat. It's a great sounding record. Jack Joseph Puig engineered it. And dad mixed it. It was an amazing experience for me. We supported the Beach Boys, so I found myself on stage without even really knowing what the hell was going on. All of a sudden I'm standing in front of a microphone and I'm going to entertain twenty thousand people at Wembley Arena.

Oh my god.

But again, just to be able to have that experience and know — it helps me understand the artists that I work with. It gives me fantastic experiences to draw on in conversation with them and to help them understand that I understand their predicaments a little better, perhaps. I think my passion for music is all encompassing, from an engineering standpoint and as a player. I love to play and make music on all kinds of instruments. I love playing bass; I love playing organ, doing string or orchestral arrangements, working on compositions. I owe so much to so many people [for] my education, which is still ongoing. I'll do...