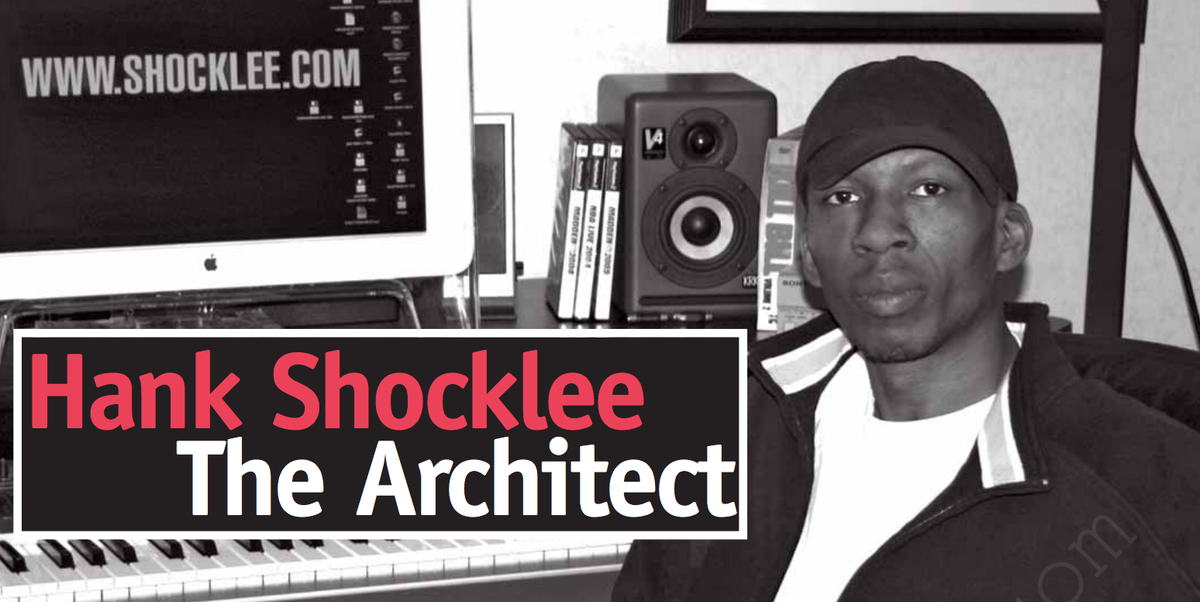

Sometimes it's too bad Tape Op doesn't offer an audio version of the magazine. Whatever you might know or not know about Hank Shocklee, it's difficult without hearing him speak, to convey the abundance of energy, good humor and all-out love for music that wells up in every word he says. After making contact with the man and trying to understand the very tip of his knowledge, it makes pristine sense that Mr. Shocklee and "The Bomb Squad" were able to carve the features of hip-hop in the late '80s and in turn, the face of modern pop music. With such prodigious influence, the lack of credit Hank seems to garner in the geeky audio realm that satellites the current recording industry is baffling. To me, Bomb Squad productions should spur the kind of endless, speculative discussions usually reserved for George Martin or Phil Spector records. But I am not, as Hank would say, a "tastemaker." It's 2005, an excellent time not to believe the hype. There is plenty here for the choir and the unconverted. Read on, plug in and tune up.

You started out as a DJ — Spectrum City, right? Chuck D was part of that?

Yeah, me and my brother [Keith Shocklee] were DJs and Chuck was the MC. And then later — and this is funny because everything kept evolving — later Norman came in.

Norman?

Norman’s Terminator [X]. He was one of our DJs and I did more of the business stuff, and then Flav joined us. So we was kinda like Public Enemy before Public Enemy.

Flavor Flav plays a lot of instruments.

He does, because Flav grew up in church. His mom was a deacon and his sister was a reverend.

So early he got playing piano, etc?

Well, you know how it is with the Baptist churches, they have drum sets, pianos, guitars and basses, and as Flavor was in there all the time he started playing each instrument.

You worked radio. Did you go to Adelphi with Chuck D?

I went to Hofstra University. Chuck went to Adelphi. And it’s funny because the policies for getting on radio at Hofstra were a lot more political than they were at Adelphi. I hooked up with Bill Stephney at Adelphi and got us hooked up so we could do our own radio show.

And this evolved into you producing the actual records when you got signed?

We started doing stuff for the radio. Everything came from that. When we did our shows we were the first ones to mix rap records back to back. Then that format was adapted by Melle Mel and Mr. Magic, who then came with The Rap Attack. There wasn’t any rap being mixed as a party thing. There were a few stations playing records, but it was never like a mix show like you see now live, like FunkMaster Flex and things of that nature. At the time there were a limited amount of records being made — we would find local rappers in the community and we would bring them in the studio and we would record beats with them. They would recite their rhymes over our beats. We would record that and then mix that into our radio show.

Were any of these the people you would work with later, like EPMD or Big Daddy Kane?

Actually it wasn’t like Kane and them. We developed and found Leaders of the New School, which was Busta Rhymes. We had a group called the Kings of Pressure, and we also worked with a group called the Young Black Teenagers.

Your brother is credited as producer on that record and you as executive producer.

Right.

Maybe I’m jumping the gun, but I was wondering, how you guys divide your work when you work together?

Oh god, it depends on who was actually doing what at the time. If you look back at the early PE [Public Enemy] stuff, my brother wasn’t associated with it, because at the time we had stopped DJ’ing and actually were doing the recording thing. He was working a job, so he wasn’t available for recording dates. So I came back and told him that we had just got a deal and did an album on Def Jam.

Was this Yo! Bum Rush the Show?

Yeah. And I kinda convinced him because I wanted him to be a part of it. And at the time we didn’t have any DJ, the S1W [Security of the First World] wasn’t there, so we was just kinda like formulating the whole PE idea, if you will.

And that idea kept on advancing.

Yeah, it’s funny because everything intertwines. Each one of us was actually doing local stuff, So for example, if you look around, the reason why a lot of people came out of the situation is because we were all kind of like business associates — we all knew each other. I was promoting events along with Chuck, and Keith and Norman were DJ’ing our events. Professor Griff did our security. We promoted Run-DMC, the Fat Boys, Spoonie Gee, Kurtis Blow, [Grandmaster] Flash — we brought all the early hip-hop to Long Island. We were one of the top promoter/DJ outfits in Long Island. Long Island for us was anything east of Queens. We played of all the colleges too. We were working non-stop. We used to throw parties and bring bands with us. One of the bands we brought with us was where Eric “Vietnam” [Sadler] was playing — he was the guitarist. We’ve had a tight little music community for the longest.

A lot of great music evolved like that. Like late ‘50s New York jazz — it’s a close-knit group of people.

Yeah! And playing together, that’s what we always wanted — a community. That’s where DJ Skribble, Busta and Gary G-Wiz, Bill Stephney, Son of Bazerk — there are so many musicians and DJs that were a part of that. So, we’re doing this and we didn’t really plan to become the artist, but there was one song we made because of the lack of songs we had to play, that we made up. We had to use up airtime and we made a song called “Public Enemy No. 1,” That particular song was kinda like a battle song that Chuck did, but the idea came from Flav — because Flav was in Queens and all these cats were talking about our show and saying how Chuck wasn’t this and blah, blah. Flav said, “Yo, I wanna let them know that you can kick it.” Chuck decided, “We’re doing this song for ‘BAU, we just want Flav to say on the air what he just told us” and he wanted him to say that on the intro to the record. So that’s how Flav’s position came to be...

Commentator!

Yeah, as commentary or what evolved as being known as the “hype man” today, because you know Flav, you know, he was so animated! He was just so excited — he was like, “Word!” and Chuck was like, “Word? Fuck that, let’s go and show these cats.” So we went and recorded “Public Enemy No. 1,” Lo and behold, that particular record was the number one requested record at the station. Now, keep in mind that we are playing real recorded records, records that were out there at radio stations from record companies. And this was back in the days when people were still recording music [off the radio] and playing on their box, because you couldn’t hear hip-hop during the daytime. So everybody would record and then play hip-hop at the park while they’re playing ball. That record — every car was going by with it, everybody was listening to it while they were playing ball. So that record caught the ears of Rick Rubin, who was out in Long Beach. And Russell Simmons and those guys came from South Queens. And WBAU’s radio broadcast frequency ranged from South Queens to the beginning of Suffolk County. That record was the number one favorite.

Did that feel pretty good?

Yeah it did, but you have to understand we were already the number one show in Queens and Long Island. When you couldn’t get WHBI, which had the Rap Attack with Mr. Magic and had the show with the Juice Crew — which was hot because they were in the city, but their show was at two in the morning — we came on ten to one and got a chance to get people. We developed the concept of doing the mix show, which was on Saturday, which was non stop mixing of all the records you would hear on Monday night, but they weren’t mixed. That show blew up bigger than the show that was on Monday, so they were going to the clubs and listening to the mix show. Mr. Magic adapted the same format and the whole thing blew up. We did Run-DMC’s first interview because one of the records we broke off WBAU was “Sucker M.C.’s,” alright? We broke that record because Russell and those guys were promoting “It’s Like That” and “Sucker M.C.’s” was the B-side. We didn’t play “It’s Like That” — we played “Sucker M.C.’s” because we liked the tempo and we liked the fact that it was street oriented and fit more in the format of the music we were playing. They [Run-DMC] were fans and one thing led to another and we end up being called by Russell and Rick [Rubin] to actually do a single, which was supposed to be by Chuck D, which was going to be “Public Enemy No. 1.” We decided to come up with a group because we wanted Flav to be in it, because Flav did the intro, which Def Jam didn’t want because they said Flav didn’t rap. We said, “Look we’re not doing it without him.” So, we decided to put together the group which was Public Enemy, which was Flav and Chuck and then we added Norm — me and Keith were the producers along with Eric Sadler and we brought in Professor Griff that did security, because when we went on the road we wanted some of our people with us.

That was major achievement. When you listen to the records, it’s hard to tell how it developed and who does what.

Which is funny because the way it was, we were all in the studio working and performing various functions — anything from finding samples to finding spoken word bits to finding intro parts, horn hits, guitar parts — everyone was doing everything. We’re in the studio with records, a sampler and everybody was musically inclined, thus we all had a love and a feel for the music. Me and Chuck, our background — I’m an arrangement fanatic. I’m a song fanatic. So one thing that I look for is songs — I edit the lyrics I make sure the arrangement is right, make sure that the song is what I consider to be something you can listen to over and over gain and not get tired of. And Chuck wrote the raps, and Eric played on a lot of the records, the beats — he was like a programmer/engineer. If anything was not in tune he would fix it. If we had a loop that wasn’t right he was, “That’s out of time.” Keith was our DJ/record specialist. He knows every record through and through parts, whether they got breakdowns, like what everybody has today. Everybody has “beat finders” who just seek the hottest drum breaks, the hottest bass breaks, turnarounds, different drum things, all these little things. We came up with a lot of different techniques in the studio that are being used today by all the manufacturers and a lot of it we came across, of course, by trial and error. Because back in the day the only sampler you had available was by Ensoniq — they made a machine called the Mirage.

I remember!

[laughs] Tight. There was a three second sampler that was like four bits — it was crazy, but that sampler was instrumental to our existence, because other than that the only other sampler you could find was the Synclavier.

And that was real expensive.

Oh man, it was like $250,000 and the only person that had one was Stevie Wonder! [laughs] Everyone said, “The Synclavier. Stevie Wonder has it!” [laughs] So we couldn’t afford that at the hip-hop level — all we had was turntables, and we would use the turntable to the best of its ability. We would also take records that were just the drum break and when the rapper got to the chorus we would scratch a musical part onto the chorus like [sings a typical PE scratch over]. That formula was something Rick Rubin heard and adopted that for Kele Le Rock. So all the early Def Jam records were patterned after the records we were doing on ‘BAU. And the reason we were doing like that is all we had was a 4-track cassette player and turntables — we had no instruments. We did have a drum machine, the Roland 8000 that doesn’t sample — it just gives you a bunch of presets. But it did have a bank to program your own beats. So we would program our own beats and use it as the basic beat, change it for the chorus and scratch in the chorus. We took that as far as we could take it. Mirage came out with this three-second sampler and Korg also entered into the sampler age with a unit called the Korg DDD-1 that allowed you to only sample for two seconds and you had to break them up. You could only sample where the kick and snare was — so you could do music parts, but you could change the sound of the kick and the snare. That was all we needed, because if you listen to a lot of the records that were done in the ‘80s like Run-DMC, they were using the DMX and it had the stock sounding snare, which was reminiscent of a lot of the groups in the ‘80s from the Midnight Starr to the Thompson Twins.

All those gated sounds

Yeah — that same, stock sound.

You didn’t want to use what everybody else was using?

We wanted to create our own sounds! So we took the record that we loved the most, which was James Brown, because you know you can always find an incredible snare. We’ll find James Brown, Parliament, Ohio Players, Kool and the Gang — we would sample their snares. An then we would go back to all our break records, whether it be “Tom Sawyer” by Rush or any of the millions of breaks records we had, and sample the kick and snare, and that sound in itself gave us an edge because our music sounded different. We wanted something that was a little more and we went looking in a lot of different places. We just happened to get a few dollars in and I found the Mirage. It gave you that three-second window, and that was an eternity for us, we’re like, “Oh my god. We can actually sample for three seconds?” So, we took that and the first thing that we did was I was playing around with it and I like this JBs record it was um...

Pass the Peas”?

Not that, “The Grunt”! I just happened to catch that little things that [makes a siren-like noise] the feel of that horn hit with the little bit of beat that was inside that — it felt so good just playing that part that we decided to create a song out of that. Eric Sadler heard it and said, “I like that,” so he took the DDD- 1, put another break on top of that break, and ended up with “Rebel Without a Pause”. We were at Chung King Studios recording that record and they had just gotten the new sampler from Akai, which was called the [S-]900, and he had in his sampler up to 30 seconds and we were like, [starts breathing heavily] “What?!” That was just amazing to us. And it was eight bits, so it moved up from four bits and that sampler sounded better and gave you more time. But when I heard it I didn’t like it because there was a feel and sound that the Mirage had at four bits and there was something good about the fact that it could only give you three seconds, because the way that it caught with a little hiccup in it that gave you that extra charge. And you didn’t get that in the 900 — that was looped correctly! I said, “Nah, I can’t feel that.” That was not working right now. So we did something that was more rugged — stayed with the Mirage but we ended up using the 900 for other things. Then manufacturers started coming up with stuff, so we went out and purchased the [EMU] SP12 and that took the game to another level, because that was sampling drum/percussion machine. That only gave you ten seconds, but the ten seconds was divided amongst the pads. So you could get 2 and 1/2 seconds for four pads, or however you divided it.

Finally, some flexibility.

Yeah! We could takes bites of stuff and actually play that with keys. Now we can take the sample and bend it and freak it, if you will, and the way that the drum machine worked, it had the cut-off, which was a flaw in the machine which would allow you to play two sounds at the same time. It was priority sensitive based upon what sound was in the bank first.

Each sampler was a new thing you had to learn to play.

Yeah, but even though it had its drawbacks it offered us a new way of expressing ourselves.

So, when you were doing the first two PE records, what were you recording to?

Two-inch tape. 24 tracks. And we had to be economical on how we recorded. For example, we might have 48 tracks of material going on.

But you gotta bring it in and out?

Yeah, so a track might have three different things on it that happen in three different parts of the record. We would load up as much as we could, samples all over the thing. So these records, engineering-wise, were very intricate to do. At Chung King we started out on the Neve board, no automation. Then we moved over to Greene Street with a Trident board. The main section gave you three frequencies you could mess with and the monitor section only gave you bass and treble, which was cool because when we were recording it, we would just take you the bass or turn up the treble. We were familiar with bass and treble. We understand that. We did a lot of our recording with that, with no automation — five of us would be sitting there. You might have three or six faders to mess with. Eric would have his three faders and Chuck would have two — so we all had to be there.

But that makes it more of a performance.

[laughs] It did! But if we had automation, we probably would have loved it because every time we had to do a mix, the minute somebody messes up, you know, you got to start all over again. When it gets three, four in the morning and we been in the studio for three, four, five days, your reflexes and responses get a little slow! So, there were times we would be taking something over 40 times and it was like, “Yo, what are we doing?!” We would get a whole thing and then someone would bring in a part a little late. Arrgh! But, like you said, it was more of a performance anyway because we didn’t use any sequencing in those records — maybe a kick, snare and hat, but not all the way through a song like people do today, which I consider to be kinda lazy. You know, let it play for five minutes and then it’s over. We would record for five minutes, go back, erase where we wanted to change the beat and have to catch it so it lined up in the spaces — the alternating beats. Whenever we put down a sample part, all of the sample parts were played by hand, so we had something that was repetitious, if you would, like [mimics horn hit repeating], that stuff would be played by hand.

So, say in “Don’t Believe the Hype” that trailing down thing...

All that stuff, and the beauty of that was, as you go down the song, your performance might get tighter or looser and it adds to the enjoyment, because people are used to feeling the elements of humanism going on.

That’s what I was going to say! It’s some of the only hip-hop music that has the sense of people playing together, which is the thing we’re all looking for. People have lost that sense of the excitement of interaction. You guys used a lot of samples, but it feels like a band.

The way we did it was like a band. Like in “Rebel Without a Pause”, Flavor played the snare portions, which was the James Brown, because Flavor had the kind of feel that was good for that. Eric might play the kick and hi hat, I would play the horn and Norman would come in and put the scratch on it. So when you get all these different feels together, it’s a band and that’s what we wanted to get, because I didn’t like sequencing.

It’s so square feeling.

Awwww! I think one of the reasons the record business is hurting today is because they’ve lost the interaction between people, because everyone has adopted the ‘Prince-Kashif-Teddy Riley-ism.’ The lone musician — he’s the band. There’s nothing wrong with that...

Well, if you’re Stevie Wonder there’s nothing wrong with that, but most people can’t do it that well.

Heh, heh — that’s so true. But the offshoots of those people, anybody who feels they have the equipment thinks that they can make a whole record. So with the advent of computers, there’s no interaction! What’s worse on top of all that, back in the days when we were doing the community thing, before you could record a record you had to at least go and rock a few parties! When you perform in front of people you have to move them and motivate them so nowadays you got cats who never performed in font of anybody, but they can make records.

And now with Pro Tools there are people making records visually, which is insane. Put a Meters record on Pro Tools and it might not look right, but it feels great!

Okay! Okay! Now you’re hitting on it so deep, because I see cats do that as well and they are sitting there looking at it and it’s getting to the point where they’re not even punching in by ear! They are looking at the waveform, setting it and allowing the machine to punch it in. Whoa, you know, what happened to the performance, B? As we move into this digital age performance is more important than ever! Anyone can make a record but the difference between the records that were being made in the ‘70s and ‘60s is that there was a performance that made connection with people. Like, me and you are trying to rock a crowd that we don’t see, alright? Music is a soul experience, no pun intended. You’re making people vibrate to your own frequency. So that’s why when you listen to the Jimi Hendrix record or the Doors or your Sly and the Family Stone, Kool and the Gang or Earth Wind and Fire — you’re feeling the energy of them cats connecting.

You know Sly’s “Que Sera Sera”? You would never hear a groove like that on a record today. It wouldn’t be allowed!

No way! It would be contrived! You know, that feeling? You can’t describe that, but in the this new world we’re living in I call it “humanism” because the thing that’s being lost today is human feel — everything has become so pre-programmed — I call it the strainer approach. Everything is going the through the strainer to strain out anything that has any life in it. So when it comes across the desk to you, it’s food with no nutrients, it’s not doing anything for you. Yeah, you move, you bop to it for a moment, but that’s only part one of the experience.

No emotional part.

Right. What makes me go back and play the song again? It has to mean something for me and that area is what we’re losing.

There’s a type of beat I associate with your work that now seems absent from hip- hop. A more aggressive thing like on Tales from the Dark Side. When did that record come out?

I’ll say 1990.

I had never heard something as complicated and layered as that record in that type of music. It was like James Brown with Eric Dolphy and the Shirelles. But you don’t lose the sense of the whole. It’s an amazing achievement of production.

Feel is more important to me than timing. Feel is more important to me than key — than anything. Many times we’re taught to cerebralize about music, and music is not that zone. There’s a thin line between when it becomes cerebral and it’s feeling good and no one knows where that line begins or ends. I get involved in every aspect of the records I make and I try to keep that feel element. It might be something as simple as this record being mixed on an API board, if you will, might sound not as good as the one mixed on the Trident. Drum machines for example, sound different and these are things people take for granted — you take your quantize off, the drum machine still has to put it in some kind of numerical value, and so you’re going to get a little of that sequencing feel. So the question is how the machine interprets that data. So in a 1200, that data’s a little more abrupt than MPC60, because that machine revolves, it creates a little groove in its quantize.

So you’re listening very carefully to each sound through each thing and the way it comes together — attention to detail.

Of course — that’s the most important thing. When I was doing Bell Biv Devoe, “Poison”, there’s some snares that are splashy and have no attack, and there’s snares that are all attack, but there’s the one that’s smacking your behind, but it’s not washed out. It’s still pleasing to the ear and at the same time, it’s gritty enough to want to hear again. I wanna feel how the bass line pulls and how it’s cracking with the snare on the one and how it’s gelling on the next beat. It’s all important. We will listen to pure mess for hours. When we was doing “Don’t Believe the Hype” Chuck was on the turntables scratching James Brown’s “Ants in the Pants.” Keith is on another table rocking a beat underneath it. Eric is there taking the S900, playing tone generator from it and pitching down an octave. We sort of sound designed, so we could take the sustain and tailor it. It’s give and take — there’s a tug of war that should be happening and that tug of war is what you get when you listen to “I Wanna Take You Higher.” At the crescendo all the instruments could be perceived as a mess, but it’s not a mess. All the harmonics melt together and create a whole new tone. We lost in the digital age the ability to have harmonics create new harmonics, because everything is isolated. And when you’re recording to a digital source the resolution is not as fine as when you’re recording to an analog source, thus you’re gonna miss a lot of things. You know how if you have a turntable on a desktop and you turn the speakers up too loud, there’s a feedback you get between the speakers going through the wood on the desktop, going back into the needle of the turntable, and it would create this kind of low frequency hum?

Yes.

Well that low frequency hum is incredible! We aren’t getting those harmonics, which is why every body is moving up to higher resolution — trying to establish these things, not what you hear in the range of 20 to 20 but what you hear in the combinations of the ranges of 20 to 20 that falls beyond that limit.

I remember early CDs had so much trouble resolving the sound of jazz records.

Ahh!

Kind of Blue or something — there were so many harmonics going on in that room, the early conversions, it ruined the echo.

Exactly! Because you put that record through a strainer. It gives you the pure essence of what it is, but it’s leaving out all the other stuff. It’s like cooking food and not being able to smell it! You know what? Heavy metal was affected by it because there’s no distortion no more! The vinyl, you could play it so it distorted again.

The second order stuff. The pleasing kind.

Yeah, that was the kind that made it like, [screams in high voice] “Yo this shit is crazy.”

Like extra air.

Yeah. Now you turn it all the way up and all you hear is just, just... you sit there and go, “Eh, uh ...not quite.” People say they listen to sound and I have to disagree with that scenario. You don’t just listen to sound. Yeah, you hear it but every cell in your body feeds off the sound so you listen to music with your being.

You listen to your records, not the sound of your records.

For example, when you listen to Stevie Wonder, he sounds like a regular old cat. But when you are open and Stevie Wonder is vibrating through your system, Stevie Wonder is making you feel so incredible! We are losing this.

And with Stevie Wonder the more you listen to it, the deeper it gets.

Ahhhhhhhhhh. Some people call it the “hair stand up” feeling. I call it the “chill bumps.” You get it when what you’re doing is pure and honest. I would sit in meetings with Russell and all these cats and say, “You know I can only make records that are one-offs. I can’t make the same records twice.” And now everybody wants everybody to make the same record twice!

Miles used to say if people asked him to play a ballad again, he’d respond, “I can’t say I love you twice.”

[cracks up] Because saying it again, you lose the honesty! It’s hollow. What is everybody doing? Everyone is going back. I don’t hear anybody talking music in terms of forward.

Son of Bazerk, ‘90, ‘91, doesn’t sound dated, but people are just starting to use some of that stuff in the neo- soul stuff.

Our studio sessions were holy ground to us. Nobody from the outside that didn’t have a direct input in the creative process was allowed to be in the studio. Your boys are not in the studio. Your manager is not in the studio. The record company is not in the studio. No fans. It’s like a team practice. When that stuff starts happening everybody starts existing on another plain, and that is the plain of how they want to be perceived. How they are and how they want to be perceived is two different things. Whichever way you go with that, if the situations arise you’re going to end up — not fake, not even in that zone, that’s an over exaggeration — but you are in a zone where you cannot be yourself and then you cannot be honest to the situation. You can’t do that with a lot of strangers around. Even when I was doing remixes for Madonna and Janet, all them, I wouldn’t allow them to come into the studio and I took a lot of heat for that.

I’ll bet.

People think, “How dare you? You’re doing my record” and I can’t explain that because they would never get it, so the only I could do would be to say, “No you can’t come in.” I wouldn’t let Russell and his people, or Rick in because at the end of the day you’ll get the record when it’s ready. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. The way it is now is that everyone’s involved in the record process man. It’s so whacked now.

It’s ruining things isn’t it?

It’s all ruined. I remember when I was at MCA and I was at a promotion meeting and people were asking the receptionist what she thought about the record. I said, “Hold it. How are you now making your decision off what someone else thinks about it?” Naturally when you ask somebody what they think of a thing they are always going to tell you something contrary to what you think or believe or they may tell you something you knew all along, but they are giving it to you so extra, you don’t even want to hear it. Whatever the case may be, it’s influencing the decision making on the situation.

I’m not sure all of these people actually like music.

In order to understand something you have to be involved in it. I never understood the guy who’s the president of the record label, and he’s a “tastemaker.” I mean, what is a tastemaker? What is that process? You mean to tell me you’re going to sit there and determine whether something is good enough to be put out or not?! I remember listening to this cat named Bob Marley. I did not like his music. I thought, “What is this? This is hideous.” My cousin, who was older, sat me down and check this out, he took Rastaman Vibration, the album — gatefold album, and opened it up had all the lyrics in it and he was telling me what it all meant and all the lyrics and at the end in this little tiny fine print it said, “this album is even good for cleaning herb.” [cracks up laughing] Okay? After he showed me the intricacies of that record and another he taught me how to listen to, which was Sly and Family Stone Stand — I didn’t like that either! He told me what that record was about. And it opened my being up, it didn’t open my ears — I was already listening to stuff. It opened my soul. He opened a door in me I never knew was even there. So that’s my whole mission in life, is to create situations that does for people what BM and Sly did for me. If tastemakers don’t like those records, then it never gets to the world and you’re doing the world a disservice.

And now, people aren’t hearing variety on the radio anymore. They don’t even know what to look for.

There’s a ten-year gap of no artists. I mean no artists. If you look at all the Jay Z’s, the Puffs, the Naz, the Marys — even the Britneys, you’re looking at a ten year run. Ever since that, with few exceptions to the rule, you can’t find any artist of any caliber of any substance that means anything to anybody.

My conspiracy theory was if you take away Britney’s machine she’s nothing, and the record company has all the power.

Whoa.

Stevie Wonder doesn’t need you — he can make a record in the basement.

Well, they’ve taken all the soul out of black music. Any kind of thought or progressive thinking has been removed from the equation now. It’s just everybody trying to make their mark in a narrow bandwidth — not saying that’s good or bad, but let’s face it, it’s not as broad as being able to have artists that have a point of view and being able to establish and maintain that position. Everybody has to be in the same bandwidth and it has brought down the quality. Everyone is getting across the same point, the same issues. Where’s all the true hip-hop? Alternative rock and roll! Hip-hop was about not sounding like the next one because that was the kiss of death, and now it is about sounding like the next one.

How do you feel now working? What do you want to do?

God, now you opened me up. My mission now is to level the playing field and be able to bring artists and songs and people expressing themselves the way they need to. I’m now working with cats who are 22, 25, 17 — who have an alternative viewpoint. I’ve never been a mainstream artist. Hip-hop was alternative — it’s not alternative anymore. So, now the thing that will excite me is the thing that is not popular now — what is underground and not getting the light of day because people don’t know where to classify it. The future is going to be in genre-less music — The kids that are coming up are cut off from the future and have recollections of the past. There will be wave of artists, whether it’s Celtic rock mixed with jazz, or jazz mixed with a little drum and bass. We’re in a beat culture. The crowds will start disappearing — no more hip-hop crowd. I grew up listening to WABC. They played Carly Simon, Kool and the Gang, Blood Sweat and Tears — it didn’t matter. People are always going to seek out good music because it deals with your soul -you don’t have any control over it, but you know that you need it. That’s the void music fills. The void is out there now and something needs to fill it. I’m tired of listening to stuff that’s old, even if it’s great — how much can I listen to something I know is old? I want to listen to something not caring about any of that. I just want the honesty of existing.