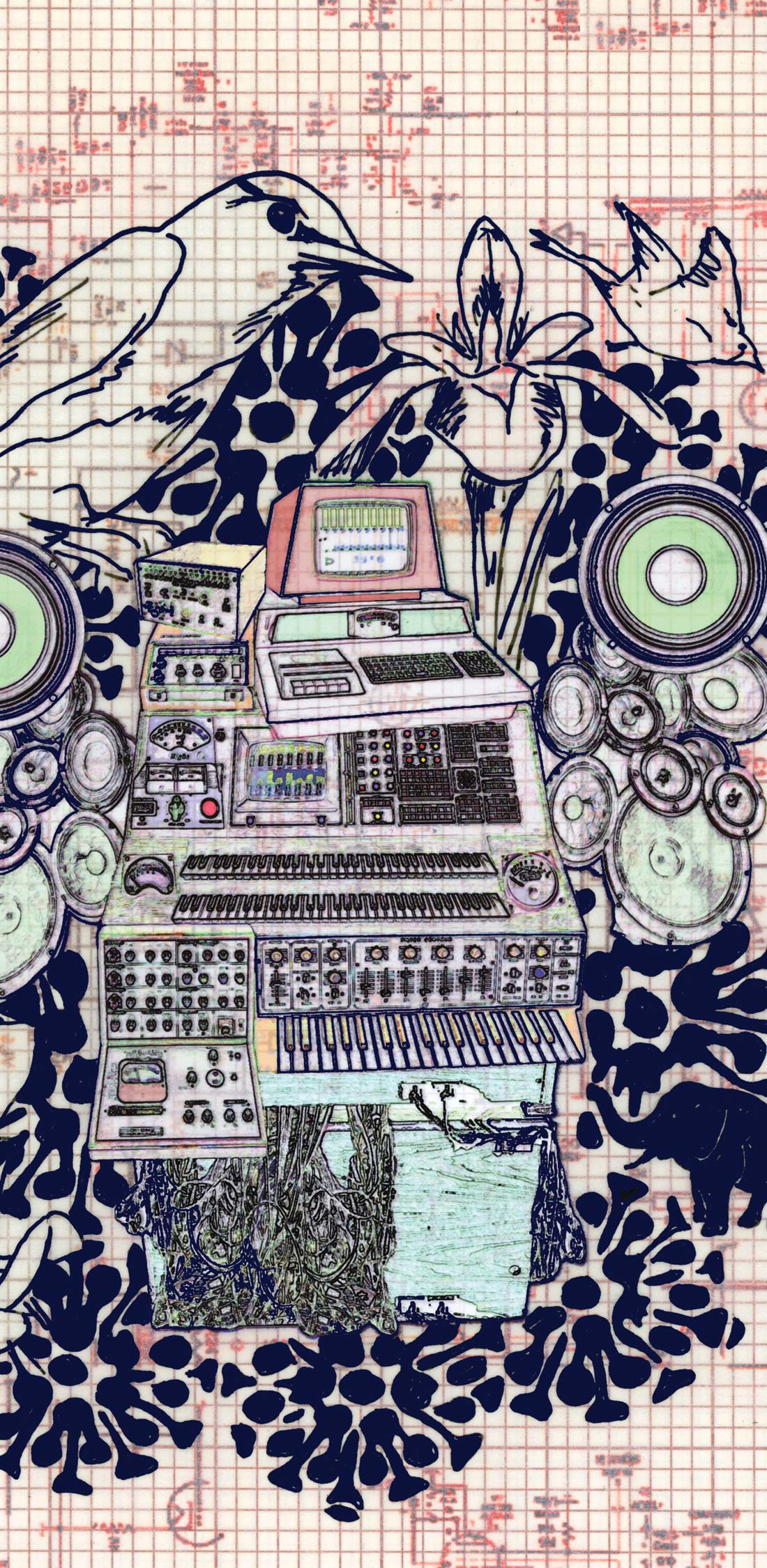

Swing open the door to the little wooden shed behind Brian Beattie's house in south Austin and wonder how it all hangs together. The walls are stacked floor-to-ceiling with what looks like a yard sale wanting to happen: There are piles of ancient audio gear and instruments, a bag of "Texas-size" popcorn, a first-place trophy from a karate meet, a bass drum dangling from a coat hanger, and a smooth-hulled contraption that's either a giant kalimba or a rowboat. There's a bare 60-watt bulb in the ceiling and cables snaking through yawning fissures in the cement floor, and — except for two stuffed chairs on the verge of collapse — there's nowhere to sit, and hardly room to stand.

Yet it's here, in this unlikely space, that Brian has crafted beautifully idiosyncratic albums that sound as rich and expansive as the studio is cluttered and cramped. And to watch him at work in this little world, which he calls the Wonder Chamber, is to watch the room suddenly come to life. Hunched over a ten-channel mixer, flanked by glowing '50s-era Ampex preamps, tube Echoplex balanced between his feet, Brian looks like Han Solo in the Millennium Falcon: You get the feeling that only he could fly this thing.

He's calm and assured amid the chaos, coaxing warm, colorful performances out of often-temperamental equipment (and musicians), carefully assembling elaborate arrangements that never quite seem under control. Whether he's recording the world's sludgiest electric guitar or finessing the details of a delicate string part, Brian always seems to know where to put the microphones, how to keep the musicians in a good mood, and why the glaring mistake you just made is the best thing about the whole song.

The first Brian-recorded album I heard was Kathy McCarty's Dead Dog's Eyeball: Songs of Daniel Johnston, a producer's tour de force in which every song sounds as if it's just beamed in from its own oddball planet. By then, Brian was already an experienced producer and engineer, having cut his teeth in the '80s recording his and Kathy's band Glass Eye, fellow art-punks Ed Hall and the inimitable Dead Milkmen (the album title Beelzebubba was his idea). More recently Brian has devoted a great deal of time to recording the legendary Daniel Johnston, whose whimsical, organic Rejected Unknown bears Brian's stamp in every moment, as does its stunning and soon- to-be-released sequel Lost and Found, on which Brian plays almost every instrument. Brian has also worked with the Asylum Street Spankers, Amy Annelle / The Places, and my bands Shearwater and Okkervil River, among others. We spent three months with Brian making the Okkervil record, Black Sheep Boy, and had just finished the final mastering fixes when I came by to pick through the wreckage and peer into the future.

This was the first multitrack record you've done in a while.

Yeah, I've gotten really into recording live to 2-track. I call it the "Tube-o-Sonic Insta-Mirror Process", since "live to 2-track" sounds boring. I take my quarter-inch mix deck, which is a beautiful old Ampex 351, and record straight to that, with everyone playing at once.

Tell me more about the 351. What was it used for, originally?

The 351 was kind of the standard professional tape deck in the late fifties, early sixties. It's just a regular tube machine that runs at fifteen ips. There were other brands, but this one was the average — the Ford of tape machines. When I bought mine I just wanted an analog mix deck, since I do all my multitracking on digital — I'd been using the original ADATs, and now I've upgraded to the HD24 — and I was just looking for something colorful to make up for the fact that my tracking medium was so plain and bland. And the 351, it's alive. Every time you listen to it, it sounds slightly different, and it gives you these beautiful degrees of saturation and distortion. By taking the same exact mix and printing it slightly louder, you can give it a whole different character.

So then you decided to bypass the digital gear completely?

Well, I wanted to try to make an entirely analog recording, but I couldn't do a multitrack recording because I didn't have the equipment. So I started thinking about my favorite recordings from the era when people couldn't multitrack. I had always been fascinated with the processes used in the mid- and late-fifties especially, like at Bradley's in Nashville — Patsy Cline — or the classic jazz recordings where you could hear the sound of the room, and that kind of electrical energy that people have when they're actually standing around playing and listening together. The thing about live to 2-track that's most special to me is that my job, when I'm mixing something like that, takes place in the exact same period of time in which the musicians are playing. So it freezes that moment as an absolutely coherent piece.

I was surprised, when I first saw you do it, that it's not like you just set everything up, press record and wait for the song to end. You're riding faders, you're adjusting effects...

It's exactly like mixing multitrack, except that whereas with multitrack you can second-guess yourself, in live to 2-track you just have to just do it, you have to just trust your ears in that moment. You do a certain amount of setting up, creating this sonic environment that you're going to be putting onto tape, and then you take things again and again. It's the way they used to do it in the olden days.

It must have taken a ton of preproduction, especially with the setups where there'd be a live combo, an orchestra, and a vocalist.

It was very complicated. They were using fewer microphones and fewer preamps, but the preparation all went into the arrangement, and the placement of the few microphones, and of course, having the musicians that were best suited for the job. I think that the reason I'm charmed by the fifties, especially, is that it was an era when musicianship and hi-fi tube technology were coming together very nicely. Multitracking wasn't standard yet, and musicians were still depending on listening to each other.

Like in those beautiful early George Jones records you played me.

Exactly. You can tell those are live vocals, you can hear that things aren't absolutely controlled, and you get a palpable sense of the depth of the music. When I'm recording to 2-track, I'm trying to transport everyone back to that era.

That's one of the things that I really like about your recordings. Even when you're multitracking, your records don't sound at all modern to me — in fact, they sound like a blast from the past, or some weird alternate past that never was.

My obsession with tape delays is probably a big part of that. Like the Echoplex — it warbles, and it distorts, and you have...