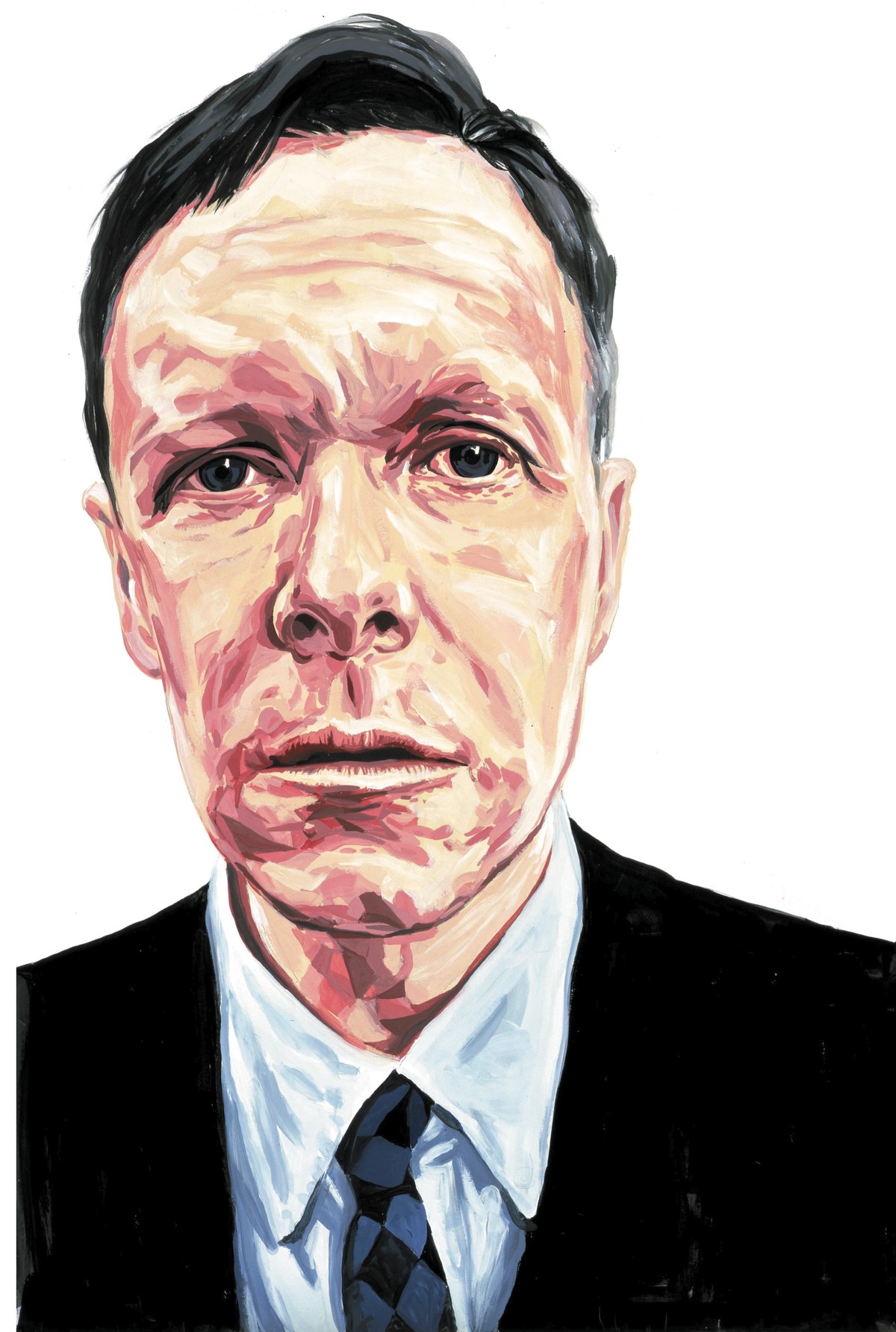

Michael Gira, co-founder of the seminal, earth-moving band Swans, has developed his skills in the studio as an artist and producer. Searching for unexpected ways to create music while maintaining the integrity of the songs, he's taken a wide range of approaches in his twenty-plus year career. Gira's current project, Angels of Light, moves him forward into enlightenment in the digital age.

Since the interview, Michael's record label, Young God Records, has kept him extremely busy, creating history with records by Akron/Family, Devendra Banhart and Lisa Germano, but he still finds time for collaboration and touring.

Tell me a little about your latest musical project, Angels of Light. How did Angels Of Light come together? How is it different than your other musical endeavors?

The first project I did after disbanding Swans in 1997 was a very complicated soundtrack-without-a-film piece called The Body Lovers. It incorporated 24-track mixes of instrumentals, as well as unmixed material; bass/drum grooves that were later looped, guitar fragments, etc., from those same sessions, to ancient — from 1982 or so — tape loops and synthesizer drones, to hand-held cassette recordings (also ancient), found sounds, to more recent patches of live Swans recordings, and also a series of non-structured sounds and fragments I'd solicited from various friends like Pan Sonic, Deathprod, Origami Republika and Bill Rieflin. So I had all this material, most of it completely unrelated and recorded over a span of 15 years, and much of it had been sitting in a trunk in a basement this whole time, and I set myself the impossible task of figuring out how to make it all work together somehow. I dumped all of it into a computer, using a mastering program called Sonic Solutions with my friend Chris Griffin in Atlanta, and just dug in, cross-fading, re- sampling pieces and flying them back in, overlaying one thing over another, sometimes recording additional material directly into the computer, letting the computer feed back sometimes as things were dumped in, then recording that, never giving any preference to something that was "professionally" recorded over the cruder material, just hacking and mangling away until the thing made some kind of musical — and "filmic" sense. It took forever and was mind numbing and exhausting, but in the end I think it's one of the best things I ever did. After that, I was fed up with the stress involved in such complex studio undertakings, so when I had enough songs for the first Angels album, I vowed to keep it simple — just acoustic guitar and voice with a few adornments here and there. I got a variety of musicians involved in the overdub stage mostly, and it just grew. One sound or instrument would imply the need for another, and before you know it, it was out of control, as usual! My biggest fault — or maybe an inverse virtue — is never knowing when to stop. In the end it was much different than the Swans' recordings though, in that most of the instruments used were traditionally "quiet" instruments, and my preoccupation wasn't so much with an overwhelming force of sound — more just trying to create a sort of visual context for the stories the words and voice told.

How much have you learned about recording and producing in your 20- odd years of making music?

Almost nothing technically about recording — intentionally! Well, I know how things work and what's possible, of course, but I have zero interest in the technical side of things. I'd rather tell someone else what I want, and let them figure it out. I've always had this sort of ridiculous self-confidence when I go into a studio, that just through force of will (and in the old days a lot of screaming and ranting at everyone involved) that I could make something happen sonically if I just pushed things enough. Often it worked, and sometimes didn't, in retrospect. Now I'm less maniacal, but I still enjoy the tension of being in a situation that's beyond my control — sometimes devolving into complete panic and chaos — and just being forced to wrangle it into shape. I enjoy the mistakes and random surprises that come from this way of working more than anything. As far as the production side of things goes, I think I've learned the importance of having the material worked out as much as possible in advance of going into the studio, but once there, to remain open to chance. Don't let your preconceptions about how things should be get in the way of new possibilities as they crop up. To me, the best thing is when things turn out completely different than how you've planned.

How has your interest in recording changed over...

The rest of this article is only available with a Basic or Premium subscription, or by purchasing back issue #53. For an upcoming year's free subscription, and our current issue on PDF...

Or Learn More