From Digital Underground and Tupac to George Clinton and Jello Biafra, Matt Kelley has engineered some fantastic sessions at San Francisco's famed Hyde Street studios. He's a total pro who knows his gear backward and forward, yet encourages artists to get their hands on the console. Kelley started as an assistant at Hyde Street almost fifteen years ago, and caught an early break when Digital Underground booked a late night session to record some tracks for their debut album. To everyone's surprise, "Sex Packets" blew up huge, critically and commercially, and, as Kelley says, "I've been riding that wave out ever since."

What kind of sessions do you generally do here at Hyde Street?

I've done a lot of different stuff over the years. I'm one of those cats who likes songs more than styles, so I've worked in a lot of different styles of music. I've been super lucky to work with some really great people: George Clinton, Jello Biafra, Augustus Pablo, Louis Johnson, Fishbone, Taylor Dayne, Depeche Mode. All sorts of cats. I like being an engineer more than a producer, actually, and I think that's helped me work in a wide variety of styles. I really enjoy doing hip- hop sessions, and I do a lot of work with Hieroglyphics and Del [tha Funkee Homosapien].

What sessions do you remember as being particularly good, or particularly awful?

Well, I don't really have awful sessions, I don't think. I've had sessions that tried my patience, with stuff not working, or feeling that you're fighting the equipment. One reason is that I don't just work with anybody who wants to work with me. Maybe back in the day I did a lot more of that, but after this amount of time I have the ability to be a bit more choosy about the folks I want to work with. So if I get a vibe that makes me feel uncomfortable, I'm likely to say, "No, I don't think this is going to work out." Rather than trying to do it and later regretting it. Now, that has very little to do with musical style. It has a lot more to do with personalities. You can be an Irish jug band and I will still have a good time recording you. If you have good songs, that's really what it's all about.

How do you get most of those clients?

Mostly it is word of mouth. People will either hear from a friend, or have picked up a record that I engineered, and will contact me that way. Also you meet people on sessions. Especially working with the P-Funk crew, I've met some very talented people and have maintained relationships with them. Clinton sessions, P-Funk sessions, are always super fun.

Yeah, tell me what that's like.

It's kind of crazy, because you never know what to expect. Often-times these sessions will happen after shows. They'll play a six-hour set and then load in and want to record the rest of the night into the next day. There isn't a formula that anybody follows, you have to be ready for anything, from basic tracks to mix. I learn so much working with George Clinton. He's probably the most even-keeled producer I've ever met. He's not one of those guys who says, "Okay, I need you to play this, this way." He surrounds himself with people he likes, people who have a style that he's looking for, and pretty much lets them develop the song.

So George is mostly directing traffic?

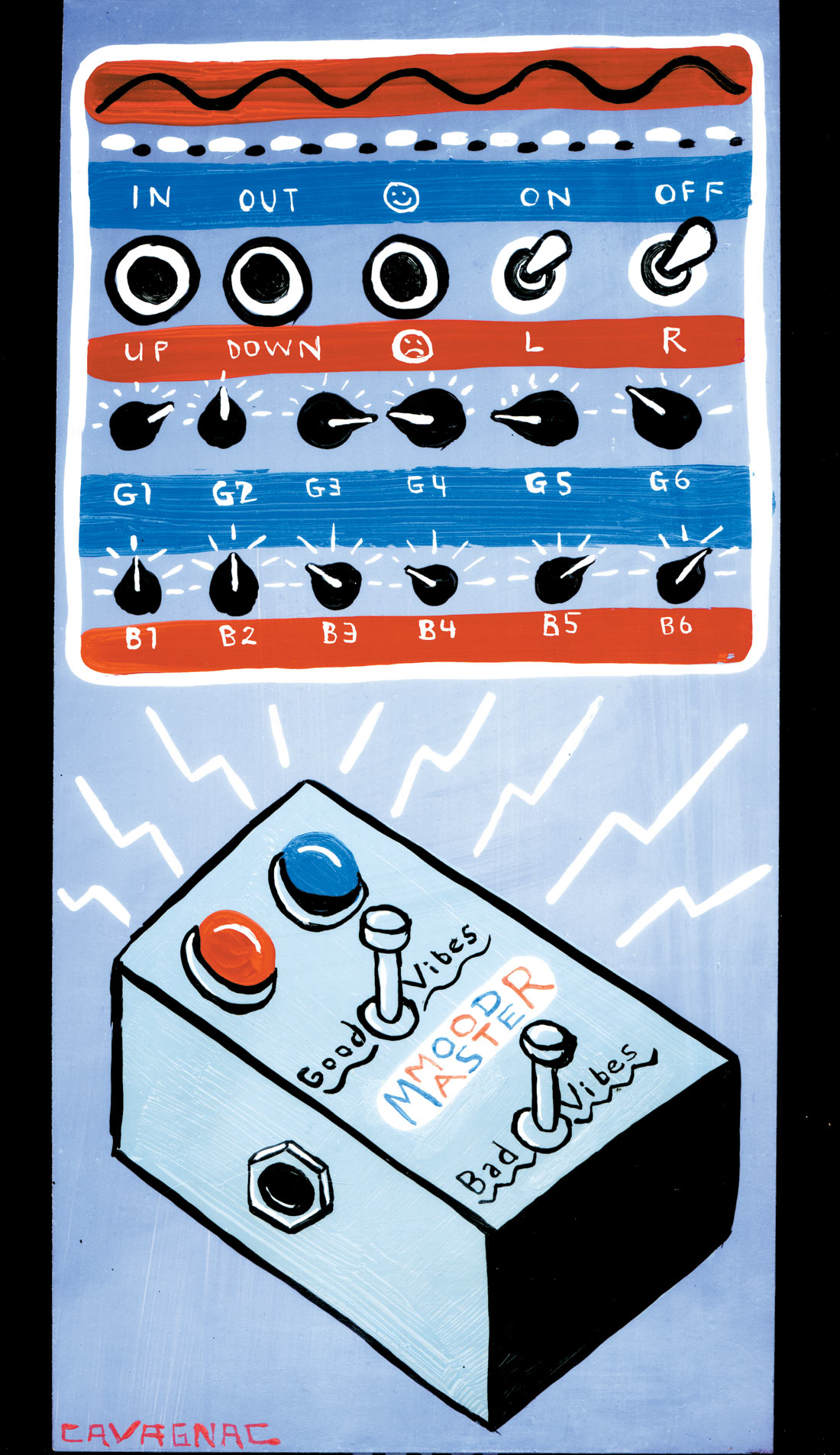

Kind of, but more just there, nodding his head and smiling. If he's not hearing something, or not liking what he hears, it's not a critical thing, but he says, "Well maybe try it more like this. More on top of it," or, "More behind it." He's never like, "No, no, this is how it has to be." Those sessions are among the funnest I've ever done — they're so freeform. Just keeping up with the musicians, making sure everybody's happy, which is really the main job of the recording engineer, I think. A lot of engineers fancy themselves producers, and a lot of artists complain to me about that. Like, "The engineer wouldn't let me do this, or try that," and I think that's crazy.

So you're pretty open-minded in sessions.

Yeah, my favorite thing is to involve the band as much as possible in the production process. Which, for me, means getting them behind the board, moving faders and playing with the EQ. Especially with regard to arranging a song in the mix. With a lot of hip-hop, for example, people just track all the grooves, with everything everywhere, then...