For forty years, David Lewiston has been recording traditional music all around the globe. He grew up in the London suburbs playing the piano and went on to study at Trinity College of Music in London, then with the Russian composer Thomas de Hartmann in New York. Thanks to de Hartmann, he was introduced to music "outside the Western canon" and decided to record it at its source. His first release, Music from the Morning of the World, was the very first stereo recording of the gamelan music of Bali. Released in 1966 as part of the landmark Explorer Series from Nonesuch records, these recordings launched his career as an engineer and producer.

So how did you manage to make those first recordings in Bali?

I had the ultimate boring job at a trade paper in New York. I asked my boss, "I'd really like to go to Southeast Asia; any chance of a leave of absence?" He said, "Sure!" We agreed that I would use a few days of that leave of absence to do a story for the magazine on banking in wartime conditions in Vietnam. How's that for a scam?

It's a good one! [laughs]

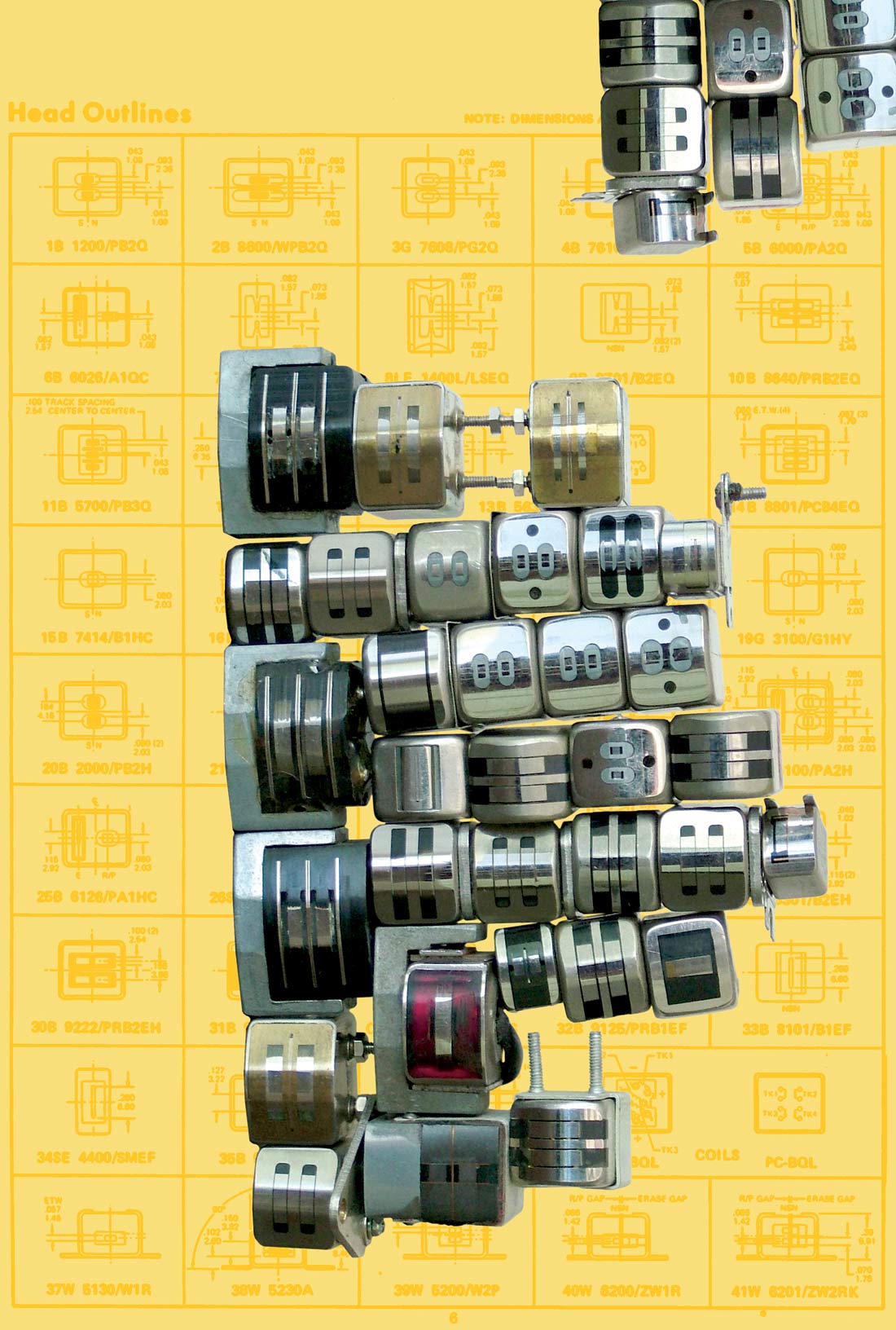

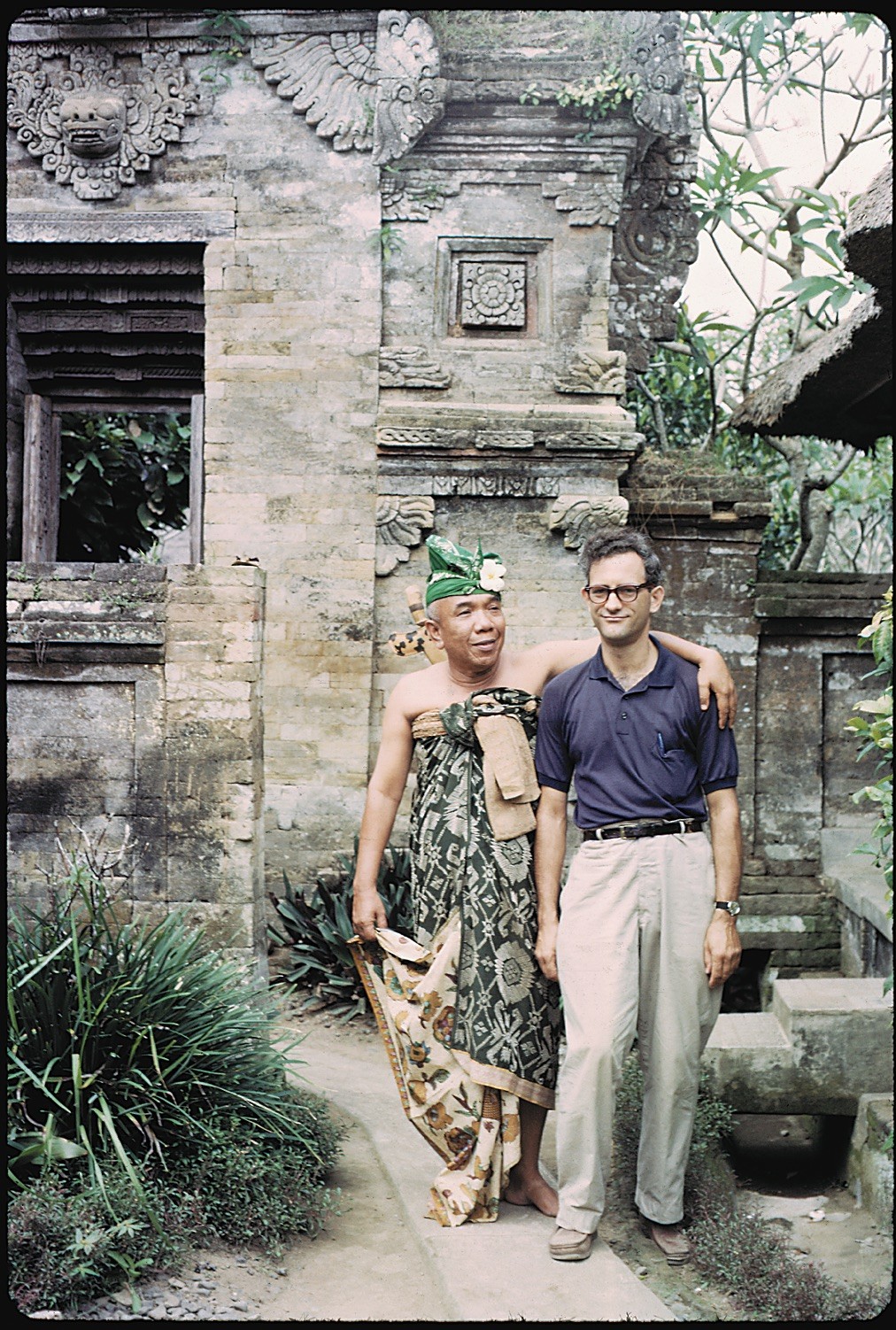

Yeah, I thought so too! I took off and went around Southeast Asia. First stop was Fiji, then Japan. After that it was Taiwan, Java and Bali. We're talking about 1966. Do you realize that there were no battery- powered stereo portable recorders at that time? The stereo Nagra hadn't been invented, and the venerable Nagra 3 was still the state-of-the-art field recorder. For stereo there were Ampex 600s and the like, but nothing that you could take around with you. When I got as far as Singapore, all I had was a mono Uher 4000. It was used by reporters a lot, weighed about eight pounds, and ran on lead acid batteries. I also had a pair of very decent small condenser mics, which a friend had lent me. Imagine my delight when I walked into a store on Orchard Road in Singapore and saw a battery-operated stereo recorder called the Concertone 727, selling for less than 200 bucks! It took five-inch reels and was pretty flimsy. But luckily, it worked during my time in Bali and Java. In Bali I struck up a friendship with a young chap who didn't want to use his princely real name, preferring to be called Dean, which he thought was really trendy! When I talked about wanting to record gamelan, he said, "Oh, no problem I'll take you around." Part of being a cultured Balinese gentlemen is a serious interest in the arts, painting, sculpture, and music and dance. So before noon, we would go to three different locations, meet the gamelan managers and arrange sessions for later that day. How's that — three sessions in a day? The first one at 2 pm for an hour or so, then the next one at 4 pm for an hour or so and then the final one after dark.

Did the recordings elicit any kind of a response?

I don't recall. But obviously they were reasonably satisfied. By today's standards, the recordings aren't that good. But at that time, there weren't any stereo recordings. I wish the geniuses who design plug-ins would find a way to eliminate distortion, a flaw of many of those early recordings. Their inadequate sound prompted me to return in the late '80s. Nonesuch was transferring some of the old masters to digital. They thought that Music from the Morning of the World was something that many people wanted, so it was in the first batch. When I listened I was really disappointed by the distortion, poor mic placement and other inadequacies. So, I went back in '87 and spent five months redoing everything.

Is there a lot of extra material floating around on tapes that have never made it on to record or CD?

Hours and hours. At the moment, I am trying to find a home for the 400 hours that I have sitting in the archives. Not just Balinese, but also Tibetan rituals, a lot of Himalayan folk, 50 five-inch tapes of South American music, plus Central America and much else.

What do you think you have the most of?

Tibetan rituals, probably, because they're so long. At one monastery it's nothing for me to record five or ten hours of material in a day. When I returned to New York in 1966, I got to meet the now-legendary Teresa (Tracey) Sterne, a fine musician who had been hired by Jac Holzman, the guy who started Elektra, to run his new Nonesuch label. Jac was interested in folk rock, and by extension, intriguing music from faraway places. So he started what was originally called the International Series,...