I'd come to a midtown Manhattan law office to meet Geoff Emerick, the infamous engineer on most of the significant recordings by The Beatles, to talk about his new memoir Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles, along with his co-author Howard Massey, an accomplished writer and engineer himself. What's most striking upon meeting Geoff is how mild-mannered he is — he's certainly quite humble considering his starring role in some of the most important recordings of the 20th century. In fact, when I come right out and refer to Geoff as a prime candidate for the "Fifth Beatle" moniker and say what Elvis Costello alludes to in his wonderful preface to Here, There and Everywhere — that Geoff's role was truly as producer, while George Martin's was more that of an A&R man or session "director" — Geoff visibly blushes before shrugging off what to him really does appear to be an outlandish suggestion. But let's face it — this is the guy who crafted some of the signature sounds we all take for granted. Paul McCartney's bass sound post-"Paperback Writer"? Geoff Emerick. Matching up the speeds and editing together two takes of "Strawberry Fields Forever" in two different keys? Geoff Emerick. George Harrison's heart-wrenching guitar sound on "Free As A Bird"? Geoff Emerick. In fact, the list goes on and on...

So, talk a little bit about how the book came to be.

Howard: Well, I interviewed Geoff in 1999 and we just kind of clicked, stayed in touch and became friends. For years I've always been saying to Geoff, "When are you going to write the book?" One day we were talking over the phone and he was telling me some story and I said, "Geoff, you've got to do a book." And much to my amazement he said, "Do you want to write it?"

Geoff: As soon as I hear a Beatle track I'm right back in that moment. So, a lot of these things were so vivid, but I didn't keep notes and stuff. I didn't have time to keep notes! Then we got my assistants who worked on those albums with me — Richard Lush came from Australia and John Smith came back from Canada and Phil McDonald, who lives in Manhattan.

H: And John Kurlander.

G: Yeah, and then all the memories would start coming back.

H: We actually listened to every Beatles track that Geoff worked on in chronological order through the course of the five years we worked on the book. We'd spend a few weeks dealing with the "She Loves You" session.

Talk a little bit about your apprentice- ship with Norman Smith, because that seems to be a really important relationship in the book.

G: Well, it was great. Norman taught me a lot. It was really the basics. One of his biggest things — and I always remember him saying this — was that all we had to do to overcome anything or fix a problem was to step back from whatever it was we were doing and go back to basics. We had a mixing console with eight mic inputs in it. We had a stereo tape recorder and a tape machine that would delay an echo and an echo chamber. That's all we had. And the EQ on the desk was just treble and bass. There were no selectable frequencies. There was a big box that was on the wall [on which] you could actually select a frequency and that was it. So Norman said, "You know Geoff, one of the things that I always do while I'm getting a balance is I lift up any one of the faders, and [then] you know if you're going to have a hit or a miss. You know if it's going to be a good session or not by the vibe coming from the studio." So I always remember Norman when I'm starting a session and the melody of the song or the vibe hits me.

He seemed to have a great sense for that too.

G: Oh, he did. He was a musician himself.

And did you feel that just being around somebody who had confidence about what they were hearing and what needed to be done helped? Did you pick up on that?

G: Yes I did. I picked up enough to reasonably know what he always told me — that you didn't manufacture a hit from the control room, that it was manufactured down on the studio floor.

Did you talk to Norman Smith?

H: No. Unfortunately. I would've loved to have. I can't wait to read his book.

Yeah, he's got a book coming out as well. Tell me about the lead up to recording "All You Need Is Love".

G: Well it was a nightmare. But basically, Brian [Epstein] told [The Beatles] that he was so excited that he'd organized this gig for them doing this broadcast, and they really weren't that interested, honestly. I mean Brian expected a better reaction from them. And then when it got nearer and nearer to the date, everyone was wondering, "Where's the song?" John could be pretty fast when he wanted to be. He only needed a line or he'd think of something he'd seen in the newspaper.

H: What did he say to Neil? "I suppose I'd better do something for that?"

G: So then he just came in with "All You Need Is Love", but they couldn't get into Abbey Road. They went to another studio to lay down a guide rhythm track, which caused problems for me because of the way it was recorded. So they come in to Abbey Road just prior to the broadcast, and basically the only thing from the original rhythm track I think we were able to use was Ringo's drums, and maybe a rhythm guitar and some harmony, but I'm not quite sure. All that broadcast is live and you've got John so nervous. You've got the live guitar solo, you've got live bass, you've got a live orchestra and anything else that was flying around there and then we mixed it that night. The only thing I remember overdubbing is a snare roll at the beginning from Ringo and then maybe two words from John that I dropped in. You know, when you see the video of the broadcast now there are a couple of words that don't sync up because we dropped them in later. So we must've just dropped in two words. Anyway, we were going to mix it that night. It was going to go down to the factory, be processed and be in the shops by the Thursday or the Friday of that week because this was done Sunday. We just slept on it because we'd been up 'til three in the morning. We just thought, "Let's get some sleep and we'll come back tomorrow and listen to it." And we left the mix set up and played it back the next day and it was fine. So we just mixed it — and I think we made just one slight adjustment and then it went down to the factory and was in the shops by the end of the week.

In the book at the point where the reader feels that everything's starting to break down, all of a sudden you come to "Ballad of John and Yoko" and you describe it really vividly — how John and Paul just had a great time.

G: That's right. When they were doing tracks, as soon as they got round the vocal part and the harmonies, they became kids again. They were joking and laughing, you know? And as soon as that was over and done and finished they walked away from the mic bickering about it.

Did you get in trouble [with EMI] for doing the wrong things? Not by the book? What do you say to your boss when he says, "Well I know it's The Beatles but..."?

G: Well, the first instance of doing something drastically different was this wretched moving [of] the bass drum mic in close to the bass drum. Someone snitched on me and management found out and said, "Well, I heard you did this yesterday. You put the bass drum mic so close to the bass drum." There was a little management meeting — I think it was before a session — and I was told that I couldn't do that, that the rules were you put it two feet away, not two inches away, because the sound pressure would damage the diaphragm in the microphone. So, there was a meeting and it was decided that I could still do it, but I could only do it on Beatles sessions. I've got a letter that actually says that. [laughing] Well, I had to be very diplomatic about it. But if I had something I wanted to try, I'd try it.

You have John Lennon goading you as well as backing you up! "Come on! Make it happen!" A bit impatiently...

G: And luckily I had the backup of them, because there was no way for management to say to them after the bass drum incident, to look at them and say, "No you can't."

Right. I mean, it was The Beatles.

G: It was just like, "Be careful Geoff." It was like a little warning, you know?

Was there a point after that, considering the elements that you added to things technologically, that The Beatles began to see you more as a colleague?

G: Sure. Well sure I mean, never really on their level. Obviously the very first thing I recorded was "Tomorrow Never Knows", with the vocal sound I got for John and the drum sound I got for Ringo. "Geoff gets the sounds" and that was just accepted as the way things were, basically. "Strawberry Fields..." was another sort of pinnacle, and I guess "A Day In The Life".

H: One of the highlights for me of this whole process: I remember Richard Lush talking with me about "A Day In The Life" and he kind of stopped and there was this long pause and he said, "Now that I think about it, it's unbelievable. This entire historic session was in our hands. A twenty-one year old and a twenty year old."

G: And that's it! George Martin was down on the floor conducting. It's just the two of us in the control room! He's twenty and I'm twenty-one. I mean, we were obviously extremely nervous doing those sort of things, but obviously we were able to do it.

You were fifteen, sixteen when you started, yeah?

G: That's right.

So even though you were twenty-one, you were a seasoned pro by "Pepper..." G: That's why I left EMI eventually, because I couldn't further my career anymore. Because when I first started [I was] going to be a mastering engineer, which I was. And if you're lucky, by the time you're forty you may be a recording engineer. That's how it was put to me. I didn't want to stay because it wasn't such a nice environment. The toss up was Air Studios with George Martin or going to Apple. George told me there was a problem with Air and I went to Apple. Paul asked me to go to Apple and rebuild the studio, which Magic Alex built. So we built a new studio, which took two years, and then obviously did the Abbey Road album at the same time. And you know, we hadn't touched on the White Album. We were all walking out and then I went back and did the Abbey Road album.

What about the White Album sessions? G: We accepted it — whatever was going on we sort of accepted it. We weren't surprised by anything. So they came back from India and there was obviously a bit of a mood there, you know, with the long hair and the way they dressed. And we're not really privy to what had been going on out there. Afterwards we found out about the problems over in India and how there was a funny vibe going on, but it was like this sort of fighting down on the studio floor, plus the business side with the Apple thing going on. And all the levels of the guitars were turned up loud. It was just not a nice environment...

It was jamming and all that, sort of aimless at times?

G: Yeah, exactly. It was crazy! I mean absolutely crazy down there, and I had terrible problems with guitars leaking onto the drums and the keyboards. There was a culmination of those things all leading up to that point when I was doing the distorted guitar sound on "Revolution" and John said, "Three months in the Army would've done you good." Why he said that I just don't know. Whether I was too slow in trying to get this new sound, I don't know. I kept my cool and I thought, "I'm not going to take this anymore." This was a Friday and on the Monday we were doing "Ob- la-di, Ob-la-da" for the sixth time. Paul had this rhythm in his head and the way he wanted to sing it and it wasn't happening. He wanted some direction and wasn't getting it from George Martin. George made a suggestion and Paul said, "I sang it two weeks ago" and George said, "Well why don't you do it like this?" Then Paul swore at George and said, "You come down and f'ing sing it, if you think you know how to sing it." And so I thought, "Oh my god!" This was a first for Paul.

For Paul to lose it?

G: In front of everybody. With George Martin.

H: George was shouting back too, which had never happened before.

G: Yeah, he raised his voice to Paul and he was red in the face, so I said to myself, "No way." And I slept it on it that night and then when George came in the next time I said to George, "I want to leave. I'm leaving. I can't take this anymore." And he said, "Well can you stay till Friday, so we can get a replacement?" And I said, "No, I want to leave now." If I would've just lifted another fader or recorded another guitar, I would've collapsed on the floor. I just wanted to get out, right? So he went up to see the manager and told him the situation. I came back down and went down the stairs and told The Beatles. And that's when John said, "It's not you Geoff, you know? It's this studio. We're just incarcerated in here. We don't want you to go." And then he made the remark about Sgt. Pepper's... being a terrible album. "Everyone thinks it's the best album we've ever done," and he said, "It's a load of shit, you know?" This was really a pointed thing to Paul. And that's basically it, and I left. I was falling apart. I was like a prisoner because there was no one supporting me. George was observing my problems, but no... not supporting me or trying to help in any way. On any session, if it's a great session, it's the producer's doing, but if it's a bad session, it's the engineer's fault. So me being the way I am, I'm taking all this personally. First, I'm being told that this sounds shit and that sounds shit and why don't you do this, and why don't you do that, you know? So, it was just all building up.

If you made a big mistake, you would've been out there on your own a little bit.

G: You would if you weren't good at your job. But then you wouldn't be there.

H: There was also the constant "Magic Alex-says-this and Magic Alex-says-that going on all the time.

G: It was just crazy. They were in charge of the sessions and not George. George had actually lost control of the sessions by this time.

Ringo said, "It wasn't like when we were doing Abbey Road that we were thinking last take, last song, last bit, last note."

G: Not to me. Now, obviously they did because of them walking away from the studio, right? So, I think in their minds that they did think it was the end.

H: I interviewed George Martin and he said that nothing was said. Nobody overtly said, "This is our last album." He said that there was a sense and that you could sort of tell it felt a little bit like they were winding it up.

After Abbey Road finishes and they walk across the zebra crossing into the sunset, other than working with Paul over the years, did you see or work with any of the ex-Beatles?

G: No, not really. Ringo's Sentimental Journey. I mixed Ringo's Vertical Man just a few years ago. So apart from "Free As A Bird" and "Real Love", that's it. I very rarely saw some of them.

When you got to Apple did you regret the decision? The mess Magic Alex had made with the sixteen little speakers in the control room...

G: It was useless. It was not up to my standards and I think I said to Paul, "If I do that, go there and build the studio, it's going to be up to the professional standard." Which it was, but it took two years to do that — gutting the whole thing out that Alex had built, building a proper studio with a floating floor and a proper mastering room.

Many years later, what were the Anthology sessions out at McCartney's studio like?

G: We gathered at Paul's studio to do those sessions and you know, with John's situation, we got the cassette with John's voice on it. Paul said, "Well let's just pretend John's gone and left us the vocal track." And that's how we got over that little hurdle. What was so odd was the fact that we gathered in the control room and the studio and sort of milled around a bit, and it seemed as though it was only three weeks previously that we'd come out of the Abbey Road sessions. Everyone's calling each other by the same nicknames and they have the same mannerisms and are doing the same things as before. It was just like being back in the studio, like the last session was two weeks ago. I mean, it was the most unbelievable feeling. There wasn't a lot of talk really, because we were there to work. We all could read each others minds as we got used to each other. We just carried on. Jeff Lynne was the producer. He was such a Beatles fan — he couldn't believe it.

H: And I remember you talking about George's guitar solo on "Free As A Bird".

G: That's unbelievable. I mean it sends shivers down my back — the emotion that comes out of that guitar solo. It really is like his thank you to John, you know?

It really is. How did you record that? Was it a Strat?

G: Well, when it comes to guitars, I don't really look at the guitar that anyone's playing. I just listen to the sounds, you see? People ask about, "What guitar was this?" and, "What did they play on that song?" I just don't know. I used to go into the studio and listen to the sound, take the amp or do what I do and that's it. That guitar solo — we liked the structure. I think George played it about six times and we picked the best bits. We were running two twenty-fours in sync. It was just a combination of two takes, I think just for two notes in the solo with a cross fade.

Is there something that you bring to a session? Is there a confidence or something else unique that you have?

G: Well, my big dream at one time was to work with Elvis Costello. And then it materialized. It was exciting and I wanted to do my best for him. I respected him as an artist because I love working with new artists. And my big complaint with records at that time was the fact that you often couldn't hear the lyrics. So, I was pushing when I was just monitoring the tracks as we're doing the basics, and I had the voice up pretty loud and that freaked him out. He apparently had trouble handling that. And then a couple of weeks passed and he sort of came round to accepting that it was going to be part of the sound of the record. He was really concerned about it. Maybe he was just being insecure. I just don't know. Maybe he wasn't. But the other approach on that — there was a sound that I wanted — this sound that was in my head. I decided to record it at 15 ips, which is unusual for a multitrack recording. And I've never used Dolby's [noise reduction] anyway, so it was 15 ips and I mixed it at 15 ips as well. I decided to have lots of movement in the sound and accent the diverse manner of the lyrics by having them come from left to right and center. And then there was one track, which I've forgotten the title of, where I said, "Well, why don't you keep singing the last words of each line and we'll cut the beginning of the next line on another track so they overlap? That way the first word of the next line will move across the last word of the previous lines?" And Elvis said, "Well, I can't do that live." And I said, "Don't worry about it." So little stuff like that.

H: Eighteen years before we ever met, I recorded the demos for Imperial Bedroom.

G: And I've never heard the demos. I mean, Elvis never brought them into the studio to play.

Where did you do those?

H: Pathway Studios in Islington.

How did you end up doing those demos?

H: It was just as a staff engineer at Pathway for a couple of years. I remember buying the album that fall and I couldn't wait to hear what Geoff Emerick was going to do to these songs that I got to know.

Where did you do Imperial Bedroom?

G: At the studios in Oxford Street. AIR. I know we cut the basic rhythm tracks really fast. It was a bit of a whirlwind. We were cutting tracks for about three or four days and after we were done with that first stretch we realized we had the basic tracks for the whole album. It was pretty fast. My goal was to get Elvis to capture the moment, because I realized when I started to work with him that as long as I had the mic placement right and the EQ and limiters ready to go, it was just all set and away you go. You'd have to capture him at the right moment to get it, you know? Because we'd be working on something and he'd sort of say, "You know I've got this other one." It was capturing the moment with him all the time.

So was it a lot of first takes? The backing tracks?

G: Not really. But it was pretty fast and pretty energetic. Maybe we went into fours and fives and went back to take twos. We probably did that.

And were there a considerable amount of overdubs, as it sounds?

G: There must've been, because I was gone a few weeks. But I know we did it in less time than Elvis was used to working for, because he had previously taken about three months and I'm sure we did it in less than that. And the sound gradually materialized, but again, it's like an album in the classic sense. And I remember when we finished it and the music publisher came and the record people came and we played it and there was just absolute silence at the end because they don't know what to do with it. So, there are those situations no matter how good what you're working on is.

Yeah. How does that make you feel?

G: Well, not too good. But what's to say? I mean on most albums you don't know what to say when the executives come in to hear them anyway. They don't have the guts, heart and soul of what's coming from the album. They're just coming up the street or whatever and you know, coming out of their office to listen to it purely as a product.

Were there other projects that stand out?

G: As a project, doing all the America albums.

Yeah. Was it good working with George again?

G: Yeah, brilliant. I mean, every one of those albums was fun. Unbelievable fun, you know? Great songs and good music.

And were those all at AIR?

G: No. Each one was done in a different location. The first one we did was in at Oxford Circus and the next one we did in Sausalito. And the next one we did in Caribou and one we did in Kauai. So, every one was a different location.

With your career, I think as fans we want to ascribe some great plan to everything, but I think you were probably just in the moment. Is that fair?

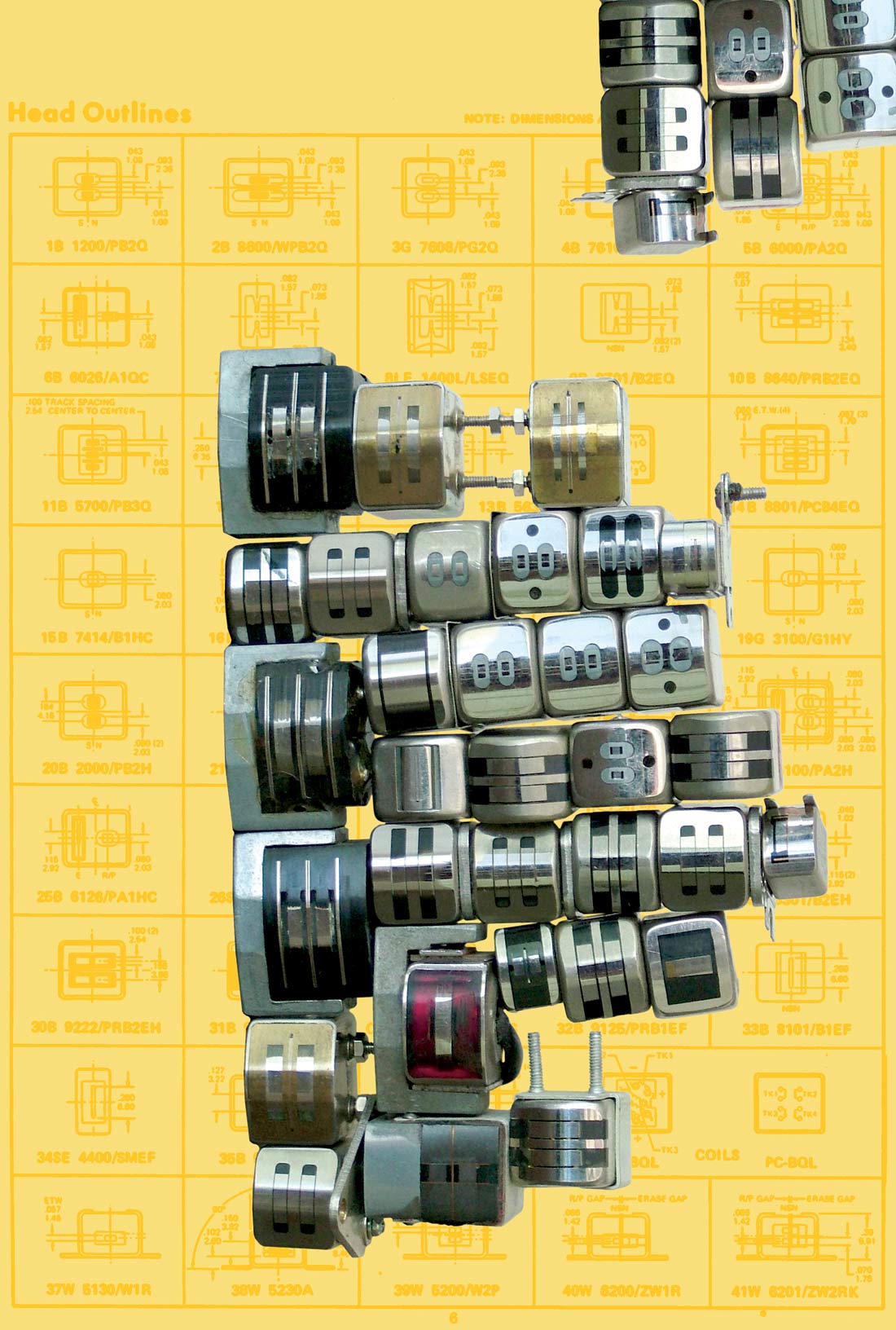

G: That is it, exactly. I mean, there in the back of my mind, because of being promoted up the ladder before going and being a recording engineer, I always listened to American records. Getting into that big bass sound those records had, listening to the Motown stuff, mastering the American records for the English market and realizing the sounds on there weren't anywhere close to what the original records sounded like. I mean, it was so much better than what was coming out in the UK. I was in the mastering room and I was playing around with the cutting heads and I was altering this and I was altering that and the sensitivity, which I wasn't supposed to do. I toyed around with things, you know? And we weren't even supposed to adjust the bias for the tape machine. If a tape came in and it sounded dull, you weren't allowed to get the bias right to make it bright and you'd have to re-cue it. I mean, it was that bad at EMI. So, I used to play around with things.

So, was that as a fan, pure curiosity or just wanting to make the records sound better?

G: Yeah, just curiosity to see what would come out to make it better. It's funny because even then I said that the only way we were going to get around the problem of getting what we were hearing in the studio into people's homes was to go to a light source — which is now what we do with CDs. But at the time it didn't exist. Then I was thinking of an optical source and a film projector. And I'm thinking, "Well, if you've got an optical disc, then maybe this is the way around these problems of degraded sound."