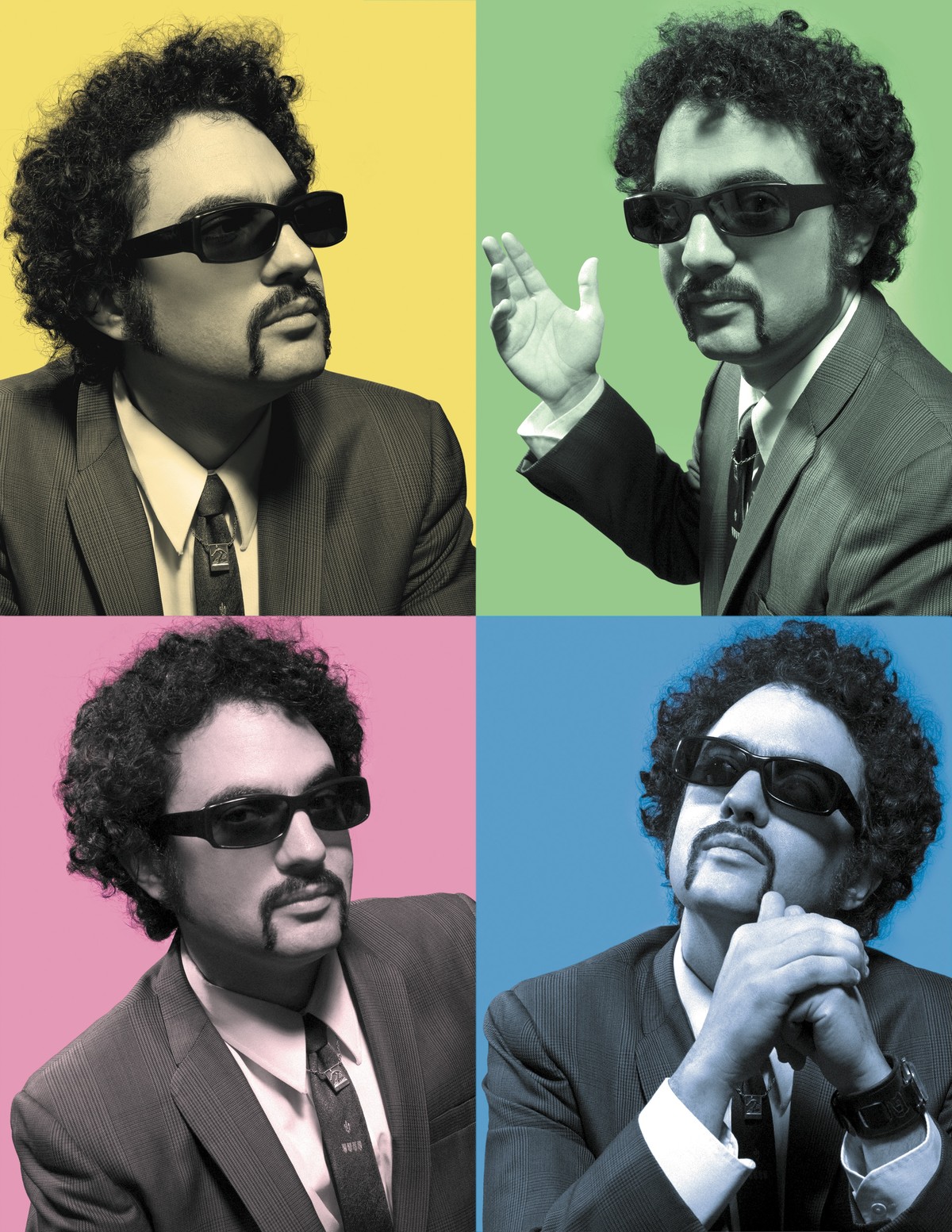

Sharon Jones may be the reigning matriarch of revivalist funk, but when I first interviewed her a year and a half ago, she was very clear about her role: she's the face and voice of the operation but not the brains. "You gotta ask Bosco that," she'd shrug whenever I tiptoed up to questions of composition, production or arrangement. As it turns out, Bosco Mann is the alter ego of New York musician Gabriel Roth, who is almost single-handedly responsible for the rebirth of funk and soul taking place in the back alleys of Brooklyn. As the leader of Daptone Records, with partner Neal Sugarman, Roth plays more roles than any one Mann should ever be able to — from bringing the funk on bass guitar to selling the funk as label executive, he does it all — and with the recent passing of James Brown, he may soon find himself one of the old school's most important surviving torch-bearers and "hardest working man in soul."

You have a pretty focused stylistic niche. Why?

When I started making records it wasn't because I turned on the radio and liked what I heard. I started making records because I was listening to old records and they sounded great. It's not really an agenda or an angle as much as it is just kind of being honest with ourselves. In articles, people say, "Aren't you just doing something that's been done before?" or "Isn't this some kind of retro fad?" First, we're not making enough money for it to be called a fad, that's for sure. We're just trying to be tasteful and try to make the kind of records that sound good and feel good. If they sound old, that's great — I dig old records. It's just hard not to read into it more than that and try to put some kind of politics behind it. But the truth is we dig old records, so we're going to try to make old records.

Can you tell me about your studio?

We built the studio in an old house in Bushwick, Brooklyn. We're not really open to the public. We do some recordings for people, either because they offer us a bunch of money to do it or because they're friends of friends. Luckily we're able to get by that way, because it's still a rough time for recording studios. We've done some stuff for Mark Ronson [Tape Op #105], who's a kind of a DJ/producer. He just did this record with Amy Winehouse as the singer, and we did a lot of tracks for him for that. We did a couple commercials. But for the most part we do our own thing. We finally got to the point where we're doing enough business to where if somebody calls and says, "I want to record my rock band, and it's a shitty band but I can give you $200," I can say, "No." My partner Neal Sugarman and I wear a lot of hats. One day we're dealing with layout of artwork and dealing with paying rent and collecting from a distributor, arranging a string section and booking shows and going on tour. We're doing everything and there are only two of us. And playing — I kind of started playing bass guitar because the bass guitar player that I was using before was too busy and I just wanted someone to be in the background. It's definitely kind of hard to produce yourself sometimes, but with the bass it's not as hard as being a singer or something like that.

The liner notes for Dap Dippin' with... say that was recorded "in Duke's basement." Is that the same place, before it found a name?

"Duke" was Duke Amayo, who is lead singer from Antibalas. In Williamsburg, he used to have a place called Afrospot, named after a Nigerian club. Upstairs, we'd have shows and concerts, and he would have kung fu classes and everything else you could imagine, and then in the basement they built a recording studio. It was a real low-ceiling, concrete, fucked up basement. So we recorded Dap Dippin'... in there, and I'm not real happy with how that record sounds. I don't mind the roughness, but there's a certain narrowness and midranginess to the sound just because of that basement, you know? I mean, you have 6 1/2 foot ceilings and concrete floors and stone walls — there's only so much you can do to try to open up the sound.

Especially considering that drums are a big part of your sound.

The basement definitely was not the best place to record drums. I think one of the things I learned was to kind of let instruments blend themselves as much as possible. If I have a horn section, I'm going to use one mic. If the trumpet player is too loud, I'm going to tell him to back up. That's just how we do it, and it just comes out to be a more natural blend. And I find the same thing with drums, too. I use very few mics on drums, usually one or two mics, sometimes three,...