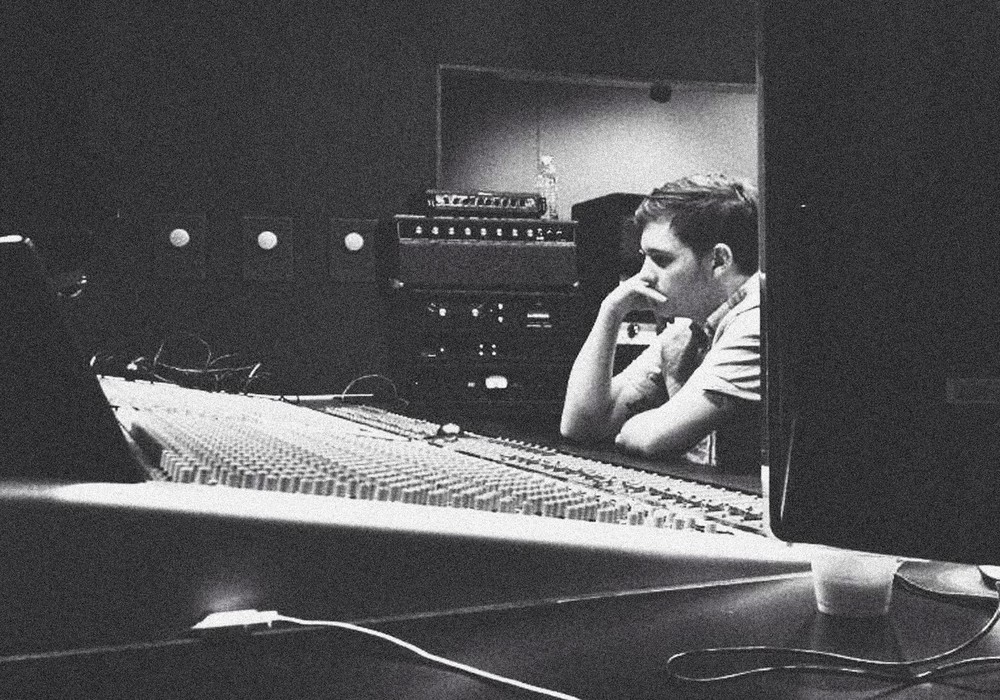

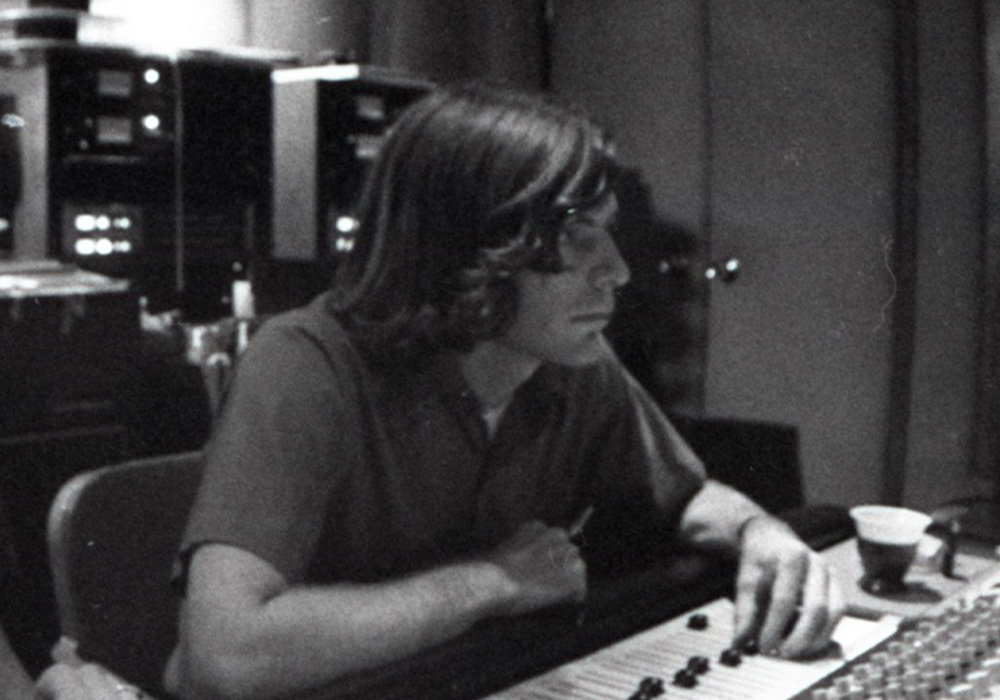

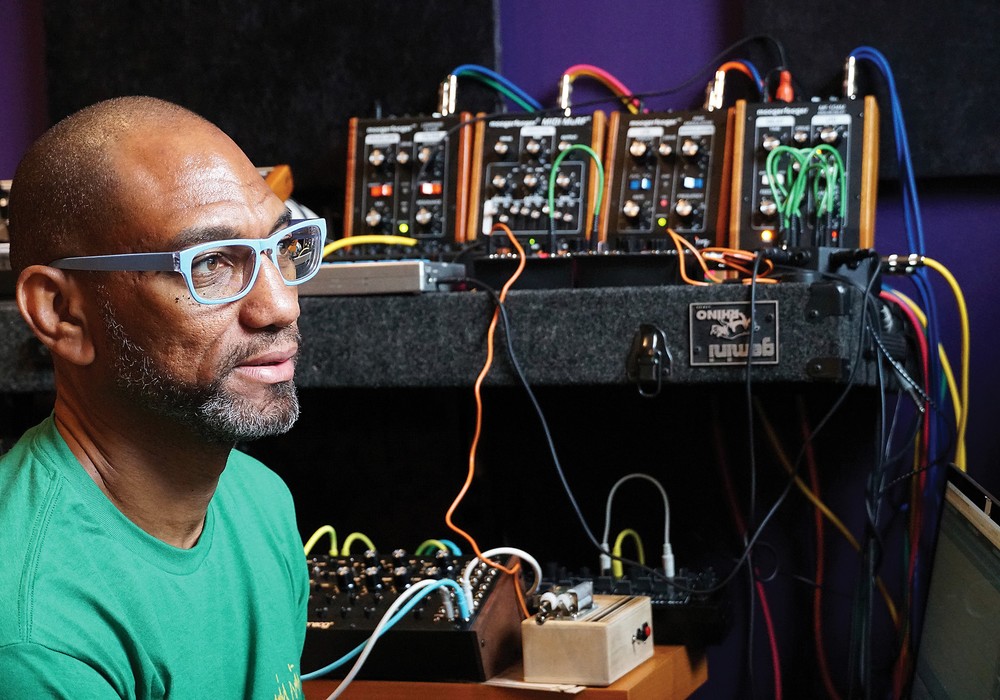

Bob Power is one of those names you might know not from reading liner notes, but instead from listening to vocal ad-libs on records he's produced or engineered. In the mid-eighties, Power found himself engineering at Calliope Studios in NYC, home to many groups that were part of what he calls the second wave of hip-hop. Bands like Stetsasonic, The Jungle Brothers, Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul went to Power to track and mix records loaded with samples, heavy bass tones and enormous 808 kick drums. By the nineties, he was producing records with D'Angelo, Erykah Badu, Me'shell Ndegecello and others at the center of modern soul music. The new millennium has seen him mixing or producing with The Roots, India.Arie, Ozomatli, and more recently the Seattle-based rock band Maktub and singer-songwriter Andrea Wittgens. His is a career that has required an openness to innovative recording strategies, new technology and most importantly, groundbreaking music. As preparation for this career, Power cites his experiences as a guitar player on the midwestern soul circuit as much as his two university degrees in music. Today, Power is a self-proclaimed "gear junkie" who remains as open to new recording strategies and technologies as ever. Every time we talk, he mentions a new piece of gear that he's excited about trying, or a new technique he's discovered. However, one soon gets the sense that a spiritual compass guides his work as much as anything else, and that vibe truly is everything when it comes to making records with him. We hung out in his Manhattan studio and talked about everything from karma to kilohertz.

What changed production-wise between the first and second wave of hip-hop? The really big difference between the first and second wave of hip-hop, for me, is the use of samples. One of the reasons A Tribe Called Quest was so amazing is that it was the first time samples were used in a really elaborate musical construction — particularly the second album, Low End Theory. That was [Q-]Tip and Ali [Shaheed Muhammad]'s real genius. It's an interesting point because the constructions, if you listen to Low End Theory musically, are very complex. If you had good session players sit down and play that, it wouldn't sound the same because part of the cool thing about samples in hip-hop is that they weren't meant to go together. As a guitar player, I would play on a new track without monitoring the old one, and it didn't sound right. I soon realized, "Oh right, I've got to play to the old track to get it to sound right." Another thing about sampling is that a hook can be a sound, and that's really cool. So, I think the palette has gotten so much larger and more varied on every level. Stetsasonic were right on the end of the first wave, and Daddy-O and Prince Paul were visionaries, though they kind of got lost in the shuffle at that point. Their second record [In FullGear] was a brilliant sample-based record.

Do you see any technology since sampling that has affected the sound of music as much?

I consider sampling as part of MIDI, and that to me was really part of the same revolution. Between the late seventies and mid-eighties, it was a really big change. I was actually scoring for TV at the time, and I was working for a more traditional, old-school musician who would write charts. With MIDI a lot of guys from that school fell by the wayside. A lot of engineers said, "That's not music," because the shit may have sounded super primitive around that time — especially to those guys who were used to sitting behind the console for years. The same arranger would set down the charts and count it off. The engineers would put up the same mics in the same way. I'm not saying it was lazy, but it was sort of complacent. When MIDI came out a lot of these guys said, "This isn't music!" and they have been selling insurance for the last thirty years. The same thing happened when hip-hop first came into New York City studios. I had played, oddly, in black bands in high school and as an undergrad on the soul band circuit. Other than the fact that hip-hop was a massive paradigm shift, or reflected a paradigm shift in the art forms of the black community, it was all the same thing to me. Unfortunately to this day engineering is kind of a white male boys club — and was very much so back then. For a lot of those guys, kids would come in dressed in what the engineers thought were funny clothes, smoking weed, sluggin' 40s. I mean, you have to understand that a kid comes from a certain environment, a tough environment, and walks into a nice recording studio where everybody pads around in expensive shoes. You've got to realize where people come from and sort of give them a little room to reflect that without saying, "What the fuck is wrong with these people?" People would walk in with turntables and the engineer would say, "Well, what do you want to do?" The artist would say, "We are going to put the track down this way." The engineer would say, "Don't you want to lock to time code?" "Time code? What do you mean, man?" I think in a weird way there was perhaps an undertone of unconscious racism there on the part of a lot of engineers. When people walk in the door, you have to say, "Hey what are you doing and what do you need?" I find that if you focus and work at getting your humanist values in the right place, everything else will fall into place.

You use loops in a lot of your stuff. Sometimes they can be heard, but not always.

I often have a bunch of little things happening, and if you listen sometimes you hear them and say, "Oh cool, there is a loop happening there." Much of the time, even on rock records, there is a lot of stuff in there that you don't hear that is really more of a feel thing. One of my theories about record making in general is that if the track is rhythmically buoyant, or sort of interesting enough, then you don't have to sell the song so hard. One of the problems with badly produced music and demos that come in is the time is not compelling. Even if it is somebody playing an acoustic guitar and singing, it's got to have this thing to it. You are immediately drawn into it, and you can really listen to what is going on.

With loops and sample-based hip- hop, where you are using loops against each other, are you trying to find the buoyancy in the interaction of those elements?

I don't think it is something that people set out to do, but an interesting byproduct of loop-based stuff is it's all in the rub of different people's time feels working at the same time. I've been playing funk music since the late sixties, and in the mid- to late eighties when MIDI and quantizing were in, things got tight, but not that funky. Then I started listening back to my favorite records — Curtis Mayfield is a perfect example — the shit is all over the place! Bongo Eddie plays percussion on a lot of Curtis Mayfield's stuff, and I have a joke with a lot of my musician friends that it sounds like he is playing in the next room. Then I realized that the funk is really in the rub, and if you listen to hip-hop stuff, that's when it's cool. If you take a loop that is against something else and you recycle or beat slice it and make it perfectly in time, it totally loses the flavor.

In the past there have been two humans, or the accident of two loops. Do you think we can now program these vibes in there?

That's a good question. I only use stuff like beat slicing when I really have to. Usually the only things that really line up pretty well are kicks and snares. That can be kind of dodgy, still. Occasionally there is one hit in the midst of a four bar loop that's off, and I'll do some time stretching in front of it or actually cut and paste that snare, but for the most part I love the rub. That's what makes it really interesting. Again, how much is too much is up to one's judgment. Perfect records are boring. Knowing how to keep the good mistakes is the fine line of production that we are always walking no matter how many records we do.

This gets tied into vibe. What are some of the things that you actually do as a producer to help create and maintain the vibe?

I am a slave to the song. When artists ask, "What's your approach?" I say, "My approach is always whatever the song wants to be." So, it really depends on the song as to what elements you think would be most effective at pulling forth the vibe of that particular song. If a song does not start taking on a life of its own at a certain point, and doesn't start telling you what to do as opposed to you telling it what to do — it's not happening. It's a weird thing to say, but everybody who makes records knows what I am talking about. If the song comes out exactly the way you had it in your head it's going to be boring. There is that wonderful, wonderful point where the song takes on a life of its own and it's great.

So what kind of things can you do to get to that point?

No matter what happened at home when you left that morning, no matter how bad the subway was, no matter how pissed you are with the record company, you put the headphones on and you are on mic, as a singer for example, and you must get into that world in the music and not worry that the lights are too bright and stuff like that. I do everything I can to make the person as comfortable as they can be. Interestingly, there's a way to read a chart and do that at the same time. Another thing on the engineering tip which I think is really key — and this is something that a lot of assistants don't understand — is that when someone comes in to work, especially an MC or singer, they should be able to walk up to the microphone, make a couple of noises and you should press record. Go! There is no reason not to have a mic and signal processing chain all up and working. Not letting the technology get in the way is a giant thing. The whole point is to make the tweaking process as transparent as possible when you are trying to be creative. One of the things I try to do when I write or produce is to make a concerted effort not to "fix the hi- hat", meaning don't get hung up on the small details. For better or worse I am a very detail-oriented practitioner. But you have to know when to put your blinders on and when to concentrate on the things that are most important to whatever stage of the process you are working in. That's where a lot of not-so- experienced engineers fall down, because they are like, "Oh wait, I gotta move this..." It's important to not give up — you always have to got to be trying to make it a little bit better, while at the same time, you also have to know that there are certain stages of the process where you have to get going quickly and then shut the fuck up.

So a tech day could be really be construed as getting the vibe for the next recording project.

With rhythm tracks — if I have money, time and we are going to do a couple of days of rhythm tracks — the first day is just a setup day. That is great because you don't have the guitar player sitting around for three hours while you doing the drums and then have to go in and be inspired. Sometimes I'll say, "If you go out for dinner and want to come back around nine and see what's going on, if you guys feel like playing, we will probably be good by then." The players will love you more for it because it means that you are taking care with how they come off on the record. I've never found anybody who wasn't happy that I was taking a lot of time to make them sound as good as possible. Again, if you approach that from a humanist level, all the other things fall into place.

But they know that is just a day to get sounds, so the pressure is off a little bit. Right. Now if I have session people coming in, I don't have that luxury. You really have to go for it and get it quickly. There is a way, with an assistant, to actually have most of the drum kit going before the guy starts playing. When the drummer comes in and sits down, obviously your levels are going to change, the placements are going to change a little, but you should pretty much know what mics you are going to use and they should be set, there should be signal flowing, and you should know if there is any part of the kit that is going to be a technical problem. I use drum techs — and again, that is another expense that most people don't usually have the luxury for — but I've learned a lot from them. There is a guy called Mike Burns whom I have known since he was 18 years old — he's in his thirties now — and he works with [Steve] Gadd and Paul Simon... he's been with everybody. Every time I've had him set up the kit it sounds great real fast. Period.

Is he working on the drums strictly, or is he also mic'ing it up?

No, he's just working on the drums. Occasionally he'll have other stuff to say, which is actually really handy. There is another guy, Gregg Keplinger — a sort of legendary guy that I worked with in Seattle a couple of years ago — who was really amazing and apparently did a lot of the big Seattle records. I did a rock band called Maktub out there a couple of years ago — great band with a really great drummer. Greg was the kind of guy where you would be in the control room and he'd hit something and you'd say, "The snare sounds a little baskety, it's a little hollow and big, but definitely hollow." He'd say, "Oh, okay" and he would go "urt" and turn one thing a tiny bit and all of a sudden it was right there. Whereas guys who are not necessarily masters, they'll be "urt... urt... urt... Let me get some tape."

And it changes too much.

And it takes forever. A master usually looks at it and says, "That will do it."

It seems we are in an era where more people are off consoles and are mixing and matching mic pres, EQs and compressors.

I think we are in a golden age of professional audio right now. A second golden age, because people are making emulations of the old stuff that actually works better. Anybody who has ever owned Neves knows what I'm talking about — it's usually switches and caps. One of the reasons I like modern microphones that are built on older principles is that they sound the same every day. I like to be able to mix and match my signal chain from the microphone all the way up to what the media is, something that is optimized for what I am recording. On a very large level, if I can afford it and I'm doing a rock band, we cut the rhythm tracks to analog tape, then the poor assistant spends a day transferring, and we finish the record in the box. I think that's something that all the geeks who are going to be reading this magazine, including myself, will hear. That and the giant differences of mic pres. I am often asked, "I'm setting up a studio for myself, what should I do?" Get a really great mic pre. It makes more of a difference than the microphone itself. I've done things with a good pre and a [SM]57 that just sound fabulous. In the modern context it's a little dark, but you can always deal with that — you can always open it up. I've been a Neve guy for years. I have twenty-four channels of Neve in racks of eight. I mean it's nuts, but over the years I just collected it to that point. And when I go to a room that might not have that stuff, I bring the stuff with me. Also, I have been totally loving APIs lately. I have a couple that are racked up, and I love to be able to track with APIs. There is just something about the speed and the punch, and it's not flavorless by any means. I love to mix and match gear when I am recording — it's actually really important. On the mix end, however, any pro mixer who tells you that they are not drifting more and more towards plug-ins and less and less toward analog inserts is lying. Even the analog stalwarts are understanding that, for the ease of recall and changes, man it's great! I picked up the mantle of becoming a better in-the-box mixer about two years ago. I am fascinated by the fact that every time I do what is fundamentally an in-the-box mix, I'm still learning something new. Funny too, it wasn't really a survival thing. I feel that if you make fundamental changes to what you love based on making money, it fucks everything up. You have to really have a passion for the thing and then everything else falls into place. I took the challenge of being a better in-the-box mixer much like I looked at MIDI and said, "Wow, all the guys who said this isn't music, look what they missed!" So, I do about half of my work at my place now. My room happens to be terrifically accurate the way I have it set up. I cheat a little, since I have a really high-end, two- mix bus that I go out through — a lot of Pendulum stuff, API, GML, Tube-Tech — really nice stuff. I can really mix and match on the two-bus the way I want to. That said, we're at the point now that when I port those mixes completely in the box, it compares quite well. With digital EQ, I find because of the lessened phase shift issues, you've got to throw the faders around a lot more than you do with analog EQ. I work on something in the box, and I find that I'm often +8 or -10 on things, where if I did that with an analog EQ it would totally suck the life out if it. I also find that digital seems much less forgiving in terms of the timbral anomalies between the different ranges of someone's voice and their proximity to the microphone. We know about slew rates and tape compression, so that's an obvious reason why analog would smooth it out a little bit. But for some it's an intangible. I find myself doing a lot more automated EQ on mixes than I ever would have thought I would have done, and I think, "Wow, what did you do in the old days?" It just didn't seem to sound that weird at different places. On the other side of the coin, there were records in the analog era where I did automate like that. For example, I mixed a Chaka Khan album — it was just so incredibly thrilling to throw up the fader and hear that. There is almost no singer with a greater dynamic range or pitch range in the business. But it kind of worked against us for a minute, because when she sang low and breathy she would really come in on the mic. When she sings really high and screams — it's almost like a muted trumpet, it's got that edge at 4 kHz that sounds like paper ripping — she would pull back. So, the proximity effect on low end was exactly the opposite of what you need to happen. It was fascinating. So, we actually had her coming back on five or six different faders with totally different signal chains, and we automated that. That's a luxury. But my thing is I don't care how you get there. It's the old Duke Ellington thing: "If it sounds good, it is good." There are certain practices that we should follow because we know that most of the time it will make a positive difference. But for the most part, if it sounds good, it's great.

Are you summing in the box?

I am summing in my [Yamaha] 02R96. At this point it is more like a giant mouse than anything else. As time goes on I use less and less from the 02R96 for several reasons. Number one, recall is easier if everything is at unity and I just have to recall my outboard stuff. Number two, what I do now when I mix on an SSL is spend a half a day to a day here on each song, getting it to sound as good as I can without any outboard, then we take it up to the big room, split it out onto the faders, and four hours later it is phenomenal. Compared to where we came from with Pro Tools and digital audio, I think Digi has been doing a tremendous job both operationally and sonically — HD sounds quite good. There are still issues. I have more of an issue with getting the spatial things happening when mixing in the box than anything else — particularly front-to-rear combined with side-to-side. You can have stuff going out, kind of forty-five degrees left or right, and then you can have stuff that's panned really hard at ninety degrees, but I have trouble getting things in between those spaces. Spatially, mixing in the box is challenging and I think everybody will say the same thing. That said, I love the challenge. It's not like every time I went up to a J or K room that it was perfect or imperfect, but the challenges are very, very different. I do love being able to get a mix pretty far here and then take it up to an SSL room and finish it off. That's great because by the time you get to the big room, you're not gating the kick drum at $2,000 a day. Psychologically it's a big deal as well.

Do you stem out the individual tracks and sum with the SSL?

Yeah, I've started working at unity where I leave the faders flat and split out into stereo pairs, and I have a way of organizing my stuff so that when I take it up to an analog desk and put the faders flat, it's exactly the same. It's really, really great. At first, I started using faders on my desk and some EQ from the 02R96, but I realized that unless I really had to, it was less flexible.

Are you doing much analog processing during your preparation before going to the big room, before hitting an SSL? Will you go out to one of your EQs or compressors and come back in?

Well, yeah. If I have program EQ on stuff, I replicate it up there and use that as a point of departure.

So you use the same analog pieces there, rather than print it?

Right, and some of my stuff travels with me. I try to keep my recall written simply in the track's comments box. But every studio has a GML EQ and Tube-Techs. The API and Pendulum compressors I either bring or I can rent. It's funny, I am just thinking about all the pieces of gear I am mentioning, and I hope this comes across: everybody is going to have a different thing to say about a different piece of gear. Some people are going to say, "I can't believe that he likes the API 2500 Bus Compressor. Man, the SSL kicks the shit out of it!" It just really depends on who you are, how you do things and how things are working that day. Music is a moving target sonically. It's never the same twice! That's one of the things that I love about it.

How much of that tallness in your sound is you, and how much of that is the history of your mixing and producing, whom you have worked with and the kind of sounds you have been recording?

That's the wonderful, incredibly complex matrix of being sonic practitioners of music, because music is constantly changing people's decisions about what instruments to use with what tonal coloration, what kind of part it is going to play — and it really boils down to what's best for the song. As a producer you always have to say, "What does the song want to do, what is going to represent this song sung by this artist as best we can?" So, if you have one part of a record that's recorded on an answering machine and another part of a record that's the London Symphony Orchestra, fine. If the songs want that thing, then it's your responsibility to pull that together. What's on tape (and I use that term all the time even though it's "what's on DAW") has such a giant bearing on how a mix will sound. Most people sort of have a way they approach things that will tilt it one direction or the other. There are certain producers with whom I always feel like it's a good marriage when I mix. Jay Dee, the hip-hop producer who passed away recently, is a perfect example. He was really good at distributing his low end, his kick and his bass. People don't pay enough attention to tuning drum samples, much less drums, but his kick and his bass were always well delineated and he had a real innate sense for where to place things in the sonic spectrum. Not so much with EQ, but just with the fundamental timbre, the instrument and the range it was playing in. It's an old adage amongst engineers: "A great mix is a great arrangement." I think that everybody who mixes will say exactly the same thing.

You've been mastering your own work more and more, and now for others. Why?

I'm going to take a lot of heat for saying this, but frankly I'm tired of going back five times, which is mostly a factor of the loudness wars. I have all this great gear, and I know what I want it to sound like, so I just finally said to myself that I should go ahead and start mastering my own stuff. From that, I've started to master for select outside clients.

You've said you work hard to get things loud, but not squished. What do you do to achieve that?

That's sort of my quest — lots of creative limiting and compression. But when I say "creative", I mean you really have to work. That's my feeling about it. I don't think there's one method. It's like anything: you try this, you try that. You see what works best. So it's just sort of looking for the right piece for that particular song. There are negative artifacts of limiting that you just try to minimize — distortion, particularity on the release. Also, if you limit badly it will take away all the pop, because you are taking the attack transients out. It's funny because I am hedging a lot about it, because there are all sorts of different things that I do. In fact, some of what I do crunches the front end of the A to D, but if I can hear it in a crunchy way, then it's not cool. There are also things you can do in your compiler — you can limit again in whatever you use for your CD compiling. I find that hitting it hard on the way into the A-to-Ds sounds different than tuning it up in the compiler. It's a different thing. The latter is somewhat less objectionable to a point and then it goes, "Ccaakkk."

So when you say you do it to a particular song, are there certain songs where you use one signal chain and others where you would use a totally different signal chain on the same record? Or are you using the same chain for the same color?

One of the big, big things about mastering is pulling the record together as a whole. It's a giant thing now. The line is a very interesting one, because you don't want everything sounding the same, but you don't want it sounding too different. It seems that if I think I want to use all the same things it doesn't sound right. It just never works out that way.

Are you ever fighting yourself between your two-bus stem processing from mixing and when you go back and are mastering the whole track? Do you use the same chains?

It's a different chain, and no, I've been very lucky with that. I know you are not supposed to master your own stuff for a bunch of reasons. But I have to say that the stuff of my own that I have mixed and mastered sounds better than anything else I've done. I am not saying I am a great mastering engineer, nor am I saying these other people are not — quite the contrary — we all know and appreciate many incredible mastering engineers. But, it just worked.

What do you see as the difference between two-bus processing on a mix and mastering?

Modern records, for the most part, are so aggressive EQ- wise, and to a certain degree compression-wise, that I wouldn't want to commit to that much at one stage of the process. I generally don't limit a mix when I am printing it. I will compress it, but in a way that it makes the music sound better — the same thing with EQs, and a part of it is twice sounds a lot better than once, just because of the way EQ curves work. Interestingly, you can do some two-bus processing on mixes that actually sounds really good, and you go, "Gee, it makes it sound great." Then you master it, whether it's you or somebody else, and then you listen to the unmastered mixes and they sound like there's Kleenex over your head. I think everybody goes through this, which is an interesting sort of psycho-sonic thing. There are certain tools — for example multiband compressors where you can solo the different bands. But if you're not careful, you can lose your reference point. If you solo a high frequency band, say from 6 kHz on up, or mute the other bands and that's all you listen to for a second, just to kind of find something in there, when you open up the track again, everything sounds horribly dull. So you gotta watch doing things like that. On the other hand, I like the fact that you can solo the different bands and say, "Okay, this is where I need to be working." I find that I need to take ear breaks every once and a while, just for two minutes and then come back and pick up again. So, it's a matter of degree. I try not to do anything too radical on the two-bus, either during mixing or mastering. Mastering is usually fine-tuning a second time.

I have heard you mention before that you also de-ess more than once at different points in the signal chain.

Or twice at different frequencies. Although, I am definitely from the school that says when you start putting two or three things on something, you had better think about your approach. Because in way, the purist in me says, "Bob, start again. You shouldn't need all these things." I'm also of the mind now to be really objective. Does it sound better? If it sounds better man, you know, I just go with whatever I had to slap on it. But often I find I need to de-ess at 2 kHz and then again at 8 kHz, 'cause they are very different areas.

Are you using software de-essers?

Yeah, I like the Waves DeEsser, not the Renaissance, but the regular one. Also, you can use de-essers as tonal shaping tools if you have enough range. The Waves one only goes down to 2 kHz. I find if there's a lot of things that are kind of spiky and snarfy in the upper midrange,ifIsetitallthewaydownto2kHzandif the vocal is all nose and real pointed, it can do a lot for smoothing it out. Another thing about de-essing which is interesting, and this comes from the analog days, is that it can help acoustic guitars. If you have an acoustic guitar that is real spiky and stringy in certain areas, a de-esser can really help tuck those places in. You have to be careful because you can really dull it out too.

Do you have any techniques, tricks, things that you do, that you really don't want other people to know about?

No! That's a quick answer. There are some guys that cover up their mix shit, and it's the silliest thing. There was a thread on Gearslutz where people were talking about who owns the materials for the record when you hand in your materials to the label. If you work in Pro Tools fundamentally, if they load that into a computer and open up Pro Tools, everything that you do is laid out for them right there. There were all these threads about what you should do, and I tried to hold back for a while, and then I finally wrote in. From my point of view, that's the most ridiculous thing I ever heard of, because music is a constantly morphing thing. If you do a certain kind of record, maybe the settings you used for one song you can use for the whole record, but people were saying, "Well they're getting get my magic EQ, my kick drum settings, my vocal settings." Nobody can possibly copy stuff you do because you approach it differently. There are zillions of little tangible and intangible things that make things come out in the way that they do. So yeah, I have really no secrets because I really think that it's a matter of the whole picture, not any one thing we do.

Have you had any examples of somebody going back into your mix and tweaking?

That's a good question. I don't think so. I think when they haven't liked the mixes they've actually redone them.

Do they come to you for that?

No, that's the whole idea. They didn't like it. [laughter] Sometimes, if they don't like something I'll be asked to redo it and change something a little. If it's not really off the wall or really damaging to the record, I'm like, "Yeah that's not going to take much, if that's important to you." But if they say something that is really damaging to the record I will tell them that, and tell them that they probably need to find somebody else to do it. There have been some times where I really think that people have used stuff that I took to a certain point and worked from that point on, but it doesn't matter. It's not important.

Tell me a little bit about teaching at NYU.

It's in its fourth year. I am teaching a class in advanced production at the Clive Davis Department of Recorded Music, Tisch School of the Arts, at NYU. I am assuming the Clive endowment program gave it its mandate, but it seems a bit separate, which is very good. I know a bunch of people who are very successful practitioners now who have come out of the Music Tech Program. The Department of Recorded Music is not part of the Music Department either, which tends to be a little more classically oriented. I was pleased to find that it's a very, very well developed four-year curriculum that includes a couple of semesters of legal issues for the record business, couple of semesters of music history and the history of recorded music. There's some people there, reggae and hip-hop historians, who are absolutely amazing. The engineering end of it is very strong. I have mostly juniors and seniors, and Jim Anderson chairs the department, who has probably recorded more good jazz and classical records than anybody. Jim is really a master and so is Nick Sansano, who runs the production end of it. Jason King is the Artistic Director. There are a bunch of people who have been in the record business for a long time, including attorney Lauren Davis. It doesn't mean that you are going to come out of there and be successful at it, but I have to say that the people I've met who are juniors and seniors really have a lot on the ball. To sort of find out where they were at the first couple of sessions, I asked them to write me critiques of three very important records, and I was very impressed with the way that they listen to music, both in terms of production technique, as well as in terms of who the artist is and what the intent of the record is. Their answers were very acute and very well developed.

Is there anything that you want to touch on that we haven't gotten to?

The one thing that's important to me when I talk to people coming up as engineers is that it's really important to understand that we are facilitators. Once you get into that mind-set, you become much more effective both for yourself as well as your clients. Remember that you are helping people along their way, and if you really open yourself and listen and try to get inside your clients' heads, several things will happen. Number one, they will trust you and will always be back. Number two, you'll never have to close the door after a session and say, "God, I'm glad that's over!" We know in reality that it doesn't always work like that, but to me that is one of the jobs of the engineer. That's why some people are very, very successful at it, because they have a way with people that makes the working relationship better, so it doesn't become a drag. The real issue is how you suss out your clients, the artists, and how you work your knowledge as an engineer in a way that's the most complimentary to that. If you approach it like that, it never, ever gets boring. It's nice to have done projects that get a lot of notoriety, and people like the way I do things, but the real deal is having amazingly positive interactions with the artists who I've worked with who are all wonderful people in their own right.

Are there any particular relationships with artists that you've especially enjoyed or that were standout experiences?

All of the artists I have worked with are really wonderful people, and most of them very singular and unique artists. It's been a nice karma for me. From A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul to Me'shell to Erykah Badu, D'Angelo — it taught me that there are certain people that stand out from the pack. I have found that the best projects and the truly groundbreaking artists have been the ones who you can't describe quickly, because they are doing something new and different. To do something in a way that hasn't really been done before, and to have it be compelling, to get an emotional reaction on our part — that's wonderful. But they have all been wonderful. I value my time with these people and value their friendship as well. I'm fortunate. Because I mix, and because I generally have as much work as I need doing that, I pick my production projects really carefully. I pick them if it seems like a good marriage, and a good marriage includes a certain intangible about the way people go about their business, plus things of musical interest to me where I think I can help them. There's a lot of artists who have come through who have a real unique way of doing things that they don't need me for and I don't want to be there if that is the case. I've walked on some really famous records part way through, only because they really wanted to do it themselves and I value my relationship with them in terms of honesty — real honesty and trust — much too much to just sit around and collect money and show up once and a while.