Where do recordists build their studios? Bedrooms? Garages? Basements? Attics? All of the above, of course. The luckiest ones, however, are able to find a dedicated space — and, Lord willing, book enough clients to cover the rent every month. But in order to build the Music Integrated Kiosk Environment (M.I.K.E.), Stuart Hyatt decided to commandeer, of all things, a derelict grain silo. He was able to finish it thanks to volunteer labor, donated materials, the help of local technical college and funding from a non-profit arts organization in Wisconsin — giving the project a pronounced regional identity. Several months later M.I.K.E. returned the favor — it produced a community-oriented album and eventually turned into a communal recording space for local artists.

It's hard to think of a less obvious home for a recording studio but Hyatt insists that M.I.K.E. makes perfect sense. "In terms of tapping into vernacular architecture and a sense of regional aesthetic, it definitely fits," he says. "Putting this in Miami or New York makes less sense — it's kind of a ubiquitous structure here in the Midwest. Activating it and inviting people in can only be a reflection of the community. Both structurally and kind of metaphorically, it made sense as a container of nutrients for people, and if that could be expanded into the realm of creativity this could be a sort of storage facility for ideas among people you were working with."

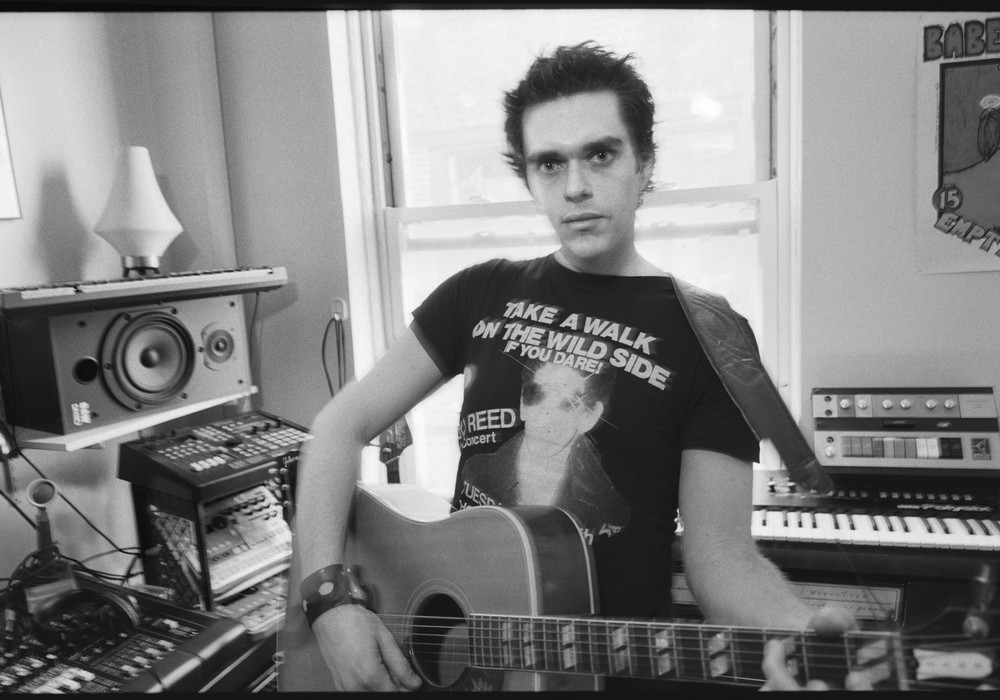

It's a grand vision, to be sure, and Hyatt comes off sounding more philosophically coherent than the architects working for studios with ten times the budget. But he's also quite the pragmatist: "They look really cool, and we got one donated," he laughs. The former is not a trivial concern; Hyatt and creative partner Richard Saxton say that the studio's outlandish appearance was deliberate, and hope that it will elicit similarly inspired performances from its inhabitants. In fact, he refers to it as a sculpture half the time. "Both Richard and I err on the side of form, coming from a visual artist's background," says Hyatt. "Nobody's going to want to pay $100 an hour to come walk into this thing and cut their demo to become a rock star — this is more of a community that, by its very presence and visual wackiness, will act as a beacon for people to come in and express themselves. We're hoping that the sculptural qualities, while they may not technically go by the rules of studio design, will provide other intangible things that are going to get the best performance out of people that are in there," he continues. "Spatial design and mechanics can affect the performance, and I'm hoping that this relies more on having an inspiring presence than its functionality as a recording studio."

At most studios the console would come before the interior decorator, but here Hyatt obsesses over color schemes and plugs everything into a Digi 002 Pro Tools setup. During the summer of 2006 Hyatt pimped his silo until it looked like something halfway between a deep-sea submersible and an alien incubation chamber. But his explorations were aimed at the heart of the local populace, and it wasn't a terrifying beastie that was gestating inside — it was a record. M.I.K.E., Volume 1 was recorded at the end of the summer, just after the studio went live. Hyatt, a recording artist himself, shepherded timid locals through the process of recording songs that he had composed specifically to capture the Wisconsin experience, not unlike what might go down if you locked Sufjan Stevens [Tape Op #70] in a tiny metal canister with a municipal band. "One of the major humps that we had to get over was having to prove that you could record a good album in there," he says, "We baptized this thing by fire, I guess. The CD is about some of the stories I've heard from the community, filtered through the voices of community members — none of whom are professional musicians, and all of whom are...