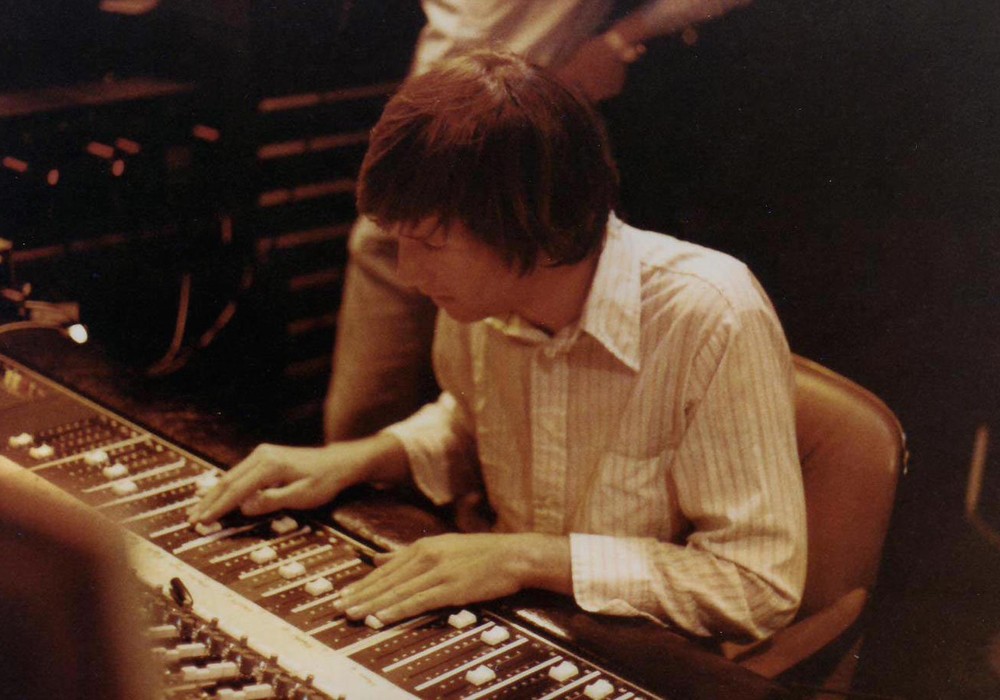

John Keane, who arguably has had a greater influence on the Athens, Georgia, music scene than any other single engineer or musician, says he "kind of fell into" his role as the city's first studio owner. He had been interested in recording since he got his first Panasonic tape deck as a kid. Later he began recording the bands he played in when he moved into a house in the Normaltown neighborhood in 1980. After experimenting with overdubs and layered sounds on multiple tape decks, he bought his first 4-track, a massive 1/4" reel-to-reel Teac 3340 from local music legend Randall Bramblett and mounted it in a Kroger shopping cart.

After recordings of his group, Phil and the Blanks, aired on the local University of Georgia radio station (WUOG), crowds at their live shows grew, and soon other local bands began hiring Keane's services. With the money he made, he graduated from a "crappy" Yamaha mixer and mics to a Ramsa mixer, an AKG 414 and a Sennheiser 421 for the kick drum. In 1983 he borrowed money from his parents to buy a 1/2" Tascam 80-8 8-track. This allowed him to begin producing higher- quality demos for dozens of artists in the burgeoning local scene including R.E.M., Guadalcanal Diary, Dashboard Saviors, Dreams So Real, Love Tractor, The El May Dukes and Club GaGa.

Eventually his engineering, producing and instrumental work established the national reputation of John Keane Studios. Over the years he has worked extensively with R.E.M., Widespread Panic and the Indigo Girls. He has additionally recorded albums with Uncle Tupelo, 10,000 Maniacs, Vic Chesnutt, Kevn Kinney, Michelle Malone, Nanci Griffith, Concrete Blonde, Grant McLennan and hundreds of others.

In 2001 Keane self-published The Musician's Guide to Pro Tools, which was praised for simplifying — and making light of — the overwhelming learning process associated with the ubiquitous application. The book was picked up by McGraw Hill and expanded in 2004. The second edition, updated for Pro Tools 7, has just been released and Keane recently began using it to teach Pro Tools in the Music Business Program at the University of Georgia.

At what point did you start to think, "Hey, this could be a long-term career." Was studio work always an ambition of yours or did it come up later?

No, recording was more of a hobby at first. In the early '80s I was playing full time with Phil and the Blanks, and we were having a go at making a living playing music. We were on the road in a crappy little van, playing in clubs up and down the coast, trying to get a record deal and writing. I was recording other bands in my spare time. At one point, about 1985, I was getting really busy in the studio recording 8- track demos and records for people. I think I was charging $25 an hour, which to me was pretty good money. I decided to leave the band and go into recording full time. I got a bank loan and bought a Tac Matchless console, which was made by Amek. I also bought an Otari MX-70 1" 16-track. The larger track capacity and better sound quality enabled me to get more work producing indie records and pre- production demos for major label bands like R.E.M., Dreams So Real and Guadalcanal Diary. By that time I had also accumulated better mics and outboard gear, and I had gotten to the point where I kind of knew what I was doing. I was starting to understand more about the role of the producer, helping bands with the creative end of what they were doing instead of just making mainly "live" recordings. I started concentrating on helping them get better sounds, picking the best songs, zeroing in on vocal performances — emphasizing the strengths and minimizing the weaknesses. It was around that time I produced the Indigo Girls' Strange Fire and Widespread Panic's Space Wrangler. Those records seem to have stood the test of time.

Athens music is known more for attitude and enthusiasm than precision and professionalism. What challenges has this presented over the years, and did it have an effect on the type of engineer and producer you became?

A lot of the early Athens bands were made up of musicians who could barely play their instruments, but it somehow worked when they all got in a room together and did their thing. I found out early on that musicians can become very self-conscious when overdubbing their parts separately. That's why my studio is designed for recording bands as live as possible. That has always seemed to be the best approach, especially with younger bands who haven't had a lot of studio experience. I like to put everybody in the same room whenever possible for tracking and then fix what needs to be fixed. My approach varies with different types of projects. I've done plenty of singer/songwriter projects where songs were built up one track at a time. I find these kinds of projects enjoyable because I often end up playing a lot of the instruments and there's more experimentation.

Is your work inspired at all by a desire to archive the music scene you came up in?

When I was making all those records it never occurred to me that I was archiving Athens' music history. I was just trying to work as much as possible so I could afford to buy better equipment to make better sounding recordings. In those days it was common for major labels to send up and coming bands into the studio for a week or so to bang out demos of all their songs before deciding whether to sign them. These sessions were especially challenging. If the demo didn't come out sounding like a finished product it could really ruin the band's chances of getting a deal, since a lot of record company people didn't have the vision to hear past a demo-quality recording and hear the quality of the songwriting. I had to learn to work very quickly and not waste even a minute of time. Sometimes the preproduction demos would end up being part of the final album. That happened a few times with R.E.M. Over the years they were constantly coming in to demo new songs. They would...