I have been privileged twice now, while interviewing studio owners for this magazine, to have encountered true mavericks. People whose views on the current state of "The Music Industry" have been so passionate and forthright that I myself have left the interviews a stronger, wiser man. The first time was several years ago when I interviewed Walter Sear of Sear Sound. The second was when I recently visited The Magic Shop, a major independent recording studio located in the SOHO neighborhood of Manhattan. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, The Magic Shop remains one of the few full-service rooms left in NYC. The studio has a rich history, having hosted Butch Vig [Tape Op #11, #115] and Sonic Youth in 1991; Interpol and Coldplay in 2007 and 2008; cutting songs with Lou Reed and Suzanne Vega; remastering the entire Rolling Stones CD catalog; working with numerous Grammy-winning bands and singer- songwriters; restoring over one hundred CDs for the Alan Lomax Collection on Rounder Records.

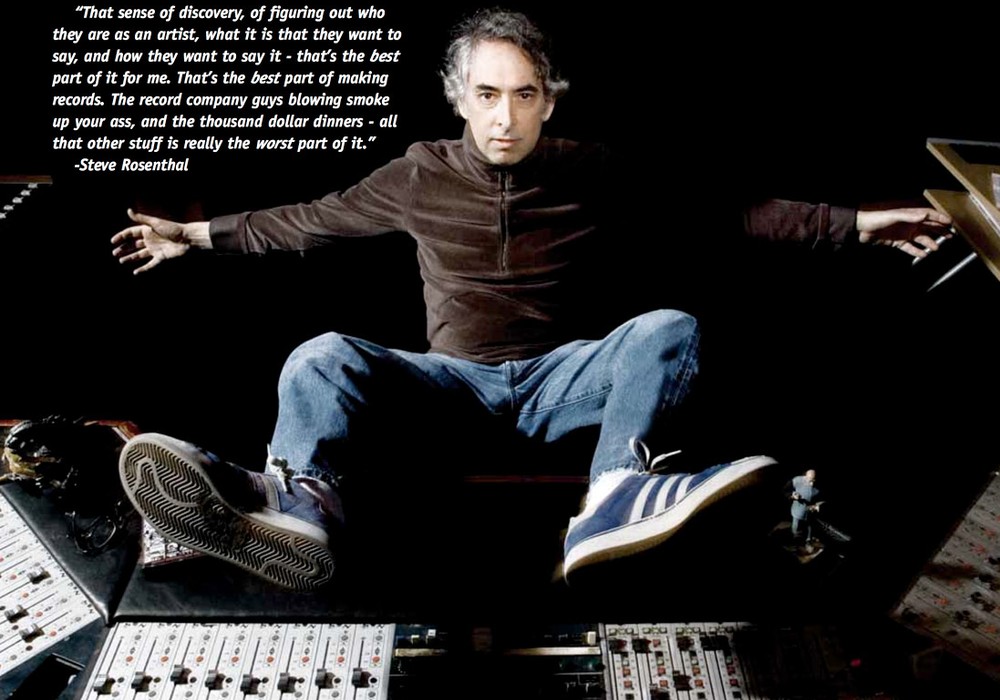

Three-time Grammy winner Steve Rosenthal is truly an experienced, gifted engineer and producer. The Living Room, the premiere singer-songwriter club in Manhattan, which Steve owns along with his wife Jennifer Gilson, is celebrating its 10th anniversary also this year. Steve was very generous with his time and very candid in his often brutally blunt assessments of where the music business has gone wrong over the many years. Due to space constraints, I unfortunately had to eliminate much of the raw interview. I would have liked to include more of Steve's remastering efforts — particularly his work with the Rolling Stones' catalog. Alas, something had to be edited out. I think you will find that this is compensated by some very interesting history and a whole lot of passion about recording and music — and about eliminating the bullshit in order to make a real connection with a real audience.

You became involved with recording in the mid-'70s when two friends of yours landed a development deal with Columbia Records.

I was at college in New Paltz with two friends from the Bronx, where I grew up. It was 1974. I left school to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I was interested in music, had started playing guitar, and my two friends got a development deal. They got studio time in Boulder, Colorado. The studio was owned by a guy from the band Firefall. We drove out to Colorado to cut their five-song demo. One of the guys had a great time while the other one was really freaked out by the experience. I ended up working on the record with my friend, the guy who was not freaked out. I really enjoyed the process of figuring out what to do and what not to do. I enjoyed being in the studio. I also enjoyed the idea that when you were in the studio, it seemed like people were very unguarded and they were forced to reveal their "true identity." If you're going to make a record and you're going to be genuine about it, you have to reveal who you are. That was really intriguing to me — as much as the musical and technical parts, actually. The notion that people strip away a lot of the bullshit and try to achieve something of value when they are in the studio intrigues me to this day. Now it's thirty-something years later and I've met a lot of really interesting people and seen them in very revealing ways — sometimes really great, sometimes incredibly bad — but not a lot of bullshit, not a lot of pretense. So I got home from Colorado and borrowed some money from my friend, Richie Berger, to pay for engineering school. Back then; there was only one school — The Recording Institute of America — in the basement of Studio 54, a studio called ODO. They had recorded Steely Dan and a bunch of other great records there. We got to go in the studio once a week for four weeks for an hour and a half each time. That was my class. In 1974, engineering was not the respectable career that it is today. Now they have schools like Full Sail, and you can tell your mother, "When I grow up I want to be a recording engineer or a producer." There was nothing like that then.

How did you get your first recording work?

Herb Abramson was really my mentor. He was one of the founders of Atlantic Records. He was the mentor to a lot of really great engineers over the years. I went to the Yellow Pages and looked up "Recording Studios." The first one alphabetically was A1 Recording Studio. I called and said, "Hi. I've got a little bit of experience and I want to learn how to be an engineer." It happened that he had an opening. I went down the next day and he offered me a job. I was his apprentice for no money for almost a year. After a year, I started getting paid a little bit.

What did you do to support yourself while you worked for free?

I drove a taxi. Flexible schedule, but driving a taxi is a crazy job and it's a tough way to make a living. I also did market research — surveys and things. When Herb started paying me, I moved to Manhattan — around the block from where he was located. I lived across the street from Miles Davis, who used to come out every Sunday in his bathrobe and hold court. I got to talk to him a number of times — he was really sweet. Herb had one of the Atlantic Records' consoles — it was tube, with rotary pots. It also had the old school-style faders — when you brought them down, things got louder. Herb was a gifted and complicated guy who taught me a lot. You had to follow his methodology — about where to mic the drums, which was three mics, and you had to use certain tube mics in certain applications. He was very specific about how to do stuff. If I'd mess around with anything, he'd yell at me. "That's not how we do it here. We do it this way. When you open up your own joint, you can do it however you want." He had some very good techniques, and I worked there for almost four years. Because he was one of the owners of Atlantic, I cut my chops doing big R&B bands, all live in studio. It was great — guitar, bass, drums, piano, horns, background vocals, lead vocal. Minimal separation. One day we had this really great soul project coming in, an artist named Lee Fields. I started setting it up the way I usually did, waiting for Herb to arrive. I called him up because he hadn't come down yet. I said, "Where are you?" And he said, "I'm not coming." And I said, "What do you mean you're not coming?" And he said, "I'm not coming. You can do this." And I said, "Are you insane?" And he said, "No. You can do it." I basically engineered this guy's record. I messed up some stuff, but they seemed happy with it. Herb basically threw me in the pool and said, "Swim." Herb was happy and the client was happy — so I started engineering for him. We did a lot of cool records. We did a record with Otis Blackwell, a great R&B writer. He was responsible for "Don't Be Cruel," "Return to Sender," "Great Balls of Fire," "Fever" and many more. It was called These are My Songs, and he sang his own compositions. Herb also taught me how to cut records. He had a disc cutter in the back room. It's a real art form and I was happy to learn about it. At the end of the session, we gave people an acetate of what was just done. I wish I had those Neumann compressors now! He had lots of Pultecs, lots of tube mics; tube Ampex machines, which we mixed down to — a mono and a stereo deck. It was a great way to learn. In 1978 I opened up a studio called Dreamland with my friend Gary Dorfman. It still exists — he still owns it. It had originally been a 24-track studio and we didn't have enough money to put 24-track gear in it, so we put in 8-track stuff — a Tascam console, Altec speakers and a piano. It was a total '70s studio — incredibly dead, rugs everywhere — even on the walls. A little drum booth and a small amp closet. The guy who built the studio, John Rhodes, did a fabulous job. The place sounded great. I was there from '78 to '84. We cut a lot of punk and new wave records with some interesting and crazy people — The Features, Popular Science, James White and the Blacks — a lot of New York bands. I did a record with Big Joe Turner there, oddly enough. We weren't big enough for the CBGBs bands. By 1978, a lot of those people already had record deals. They were going to the Power Station or Media — places like that. We got a lot of second-level people. I also had a little record company when I was at Dreamland, called Rocking Horse Records, named after that part in the Sgt. Pepper's song. We put out a couple of new wave bands. I was in one of the bands, the TV Babies. We put out three or four records. I played guitar and sang and my ex-wife played the drums and sang. I always wanted to be a successful artist, but I understand why I wasn't one. Eventually I decided it was a good time to have my own place. I found someone who was willing to invest in a studio with me. His name was George Hirsch. He was a really wonderful guy. Without George — and most importantly my son Graham, who passed away in 2001 — the Magic Shop wouldn't exist. Sadly, George passed away as well — about a year and a half after the Magic Shop was built. There are certain people who are like angels in our lives. Graham and George were the angels in my life. George was here and did some absolutely transformative things, and then he was gone. He saw a little bit of the studio before he passed away. He saw the fact that it was going to work, but it was really an act of faith on his part.

Like, "If you build it, they will come."

I had some faith in my ability to do it, and I had some vision. This was an empty photographer's loft. I spent almost four months walking from where the Twin Towers used to be to 14th Street, from the river to Avenue A. Every day I would walk up and down the streets looking for loft spaces. That's how I found this place. I wanted to cut out the broker fee. I had a very specific idea that I wanted high ceilings and no columns, so I could get big drum sounds. It took about eight months to build, from '87 to '88. I was here every day sucking in the sheetrock and chemicals. The studio was designed by a professional studio designer, Larry Carswell, and built by me and several of my friends, with special help from Bill and Artie Horwedell. We tried to do everything right. All the floors, ceilings and walls are at splayed angles. It looks like a rectangle, but it's not. It's all floated — everything that you're supposed to do — but of course you never really know how it's going to sound until someone goes in there and bangs the drums or sings. It was very difficult to get people to come here at first. Musicians and producers tend to be very superstitious, and they only want to go to places that are already successful. It was like a Catch 22 — how the hell do you get to be successful when you can't get any people to come? So for the first year or year and a half, it was mostly my clients that I had developed — my engineering clientele from previous studio work. Most of the major label people that came at the beginning thought I was totally nuts. It was all MIDI and "squeaky girl" hysteria then — everyone sounded like Madonna. Label people were, "Why are you building a live room?" I was, "Well, I want people to play." They said, "Nobody's going to play. They're going to use sequencers and synths. That's music. What the fuck are you doing?" I also went and bought this rather strange Neve console. They looked at the console and said, "What is this?" They wanted to work on SSL [consoles].

In a way, you really anticipated the return to vintage gear.

I just believed — and still do — that this particular equipment sounded better. When I sat in front of an old Neve, I was immediately impressed. It just seemed like a no-brainer that these mic pres and hand-wired design sounded infinitely better than any op-amp board. When I had a chance to build a studio I thought, "I'm going to build a studio where the most important thing is that stuff should sound good!" I wanted to have as pure of a signal chain as possible. I'm a believer that the less stuff in the way between the microphone and the tape machine, or Pro Tools, the better. A lot of times, we don't even go through the fader. We'll just go through the bottom of the mic pre or the mic pre point on the patchbay — which is literally about as clean as you can get with a class A mic pre and a tube mic. I think you'll get the best of what someone is giving you. In order to find the kind of console I wanted for the studio, I took a trip to England and spent a bunch of time there. I was lucky enough to locate a console owned by Alexander Fulcher, who operated a studio in London. I eventually convinced him to sell it to me and had it shipped over. The console was originally installed at the BBC's Maida Vale Studios. Rupert Neve visited early on, within the first couple of years after The Magic Shop opened. We were all terrified that he was going to tell us that the console was bad and that we should bag it. He came in with his oscilloscope and performed tests on the console. He also performed some tests on us, which was interesting because he is very much into the idea of perceived frequencies — that it's not just what you hear, but rather what your brain processes, that you may not think you actually are "hearing." He played back 80 kHz and 90 kHz tones through the console, showing us that we could actually perceive those frequencies — even though we didn't think we could. After going through all of that, he told me, "Steve the console is fine. You can go ahead and use it." We were really happy. About five years after I opened, my friend, Nat Priest from Music Valve Electronics, walked in the studio with a photo of a console that looked identical to the one that I had. He said, "Do you think we should get this?" I said, "Yes — by all means!" We got on a plane the next day, went to England, and found a second console, which was the 24 input version of the 32 channel console that I already had. Nat put the two consoles together, and Rupert was very helpful again. He sent us schematics and drawings about how we should join the busses and stuff like that. So our 1971 Neve went from 32 inputs to 56 inputs, which it is now. When I first opened, people looked at the console and asked, "What the hell is this? How do you use it? Why did you buy it?" The combination of having a live room and this console did not make it easy to book people at first.

Eventually Sonic Youth and some other big acts booked time.

Bob Riley and Elly Brown from Grace Pool had a deal on Warner, and they walked in and said, "We love this place. We want to be here for two months." I was flabbergasted. It was a really wonderful thing when they did that. I also started working on records for my friend Ron Levy at Rounder. He had just started this company called Bullseye Blues. I got to record Charles Brown, Champion Jack Dupree, Larry Davis and a bunch of really great blues records here. I started spec-ing time with songwriters that I liked, like Brenda Kahn. I've always liked songwriters. I got really lucky when Suzanne Vega came here to work. She's a great artist and one of my favorite people. Butch Vig came and did Sonic Youth's Dirty record here. The Ramones came and did Mondo Bizarro with Ed Stasium. In the span of about six months I got an incredible stamp of approval from all of these really fabulous artists who said, "You can record here." I always say quite frankly that thanks to these first major bands and artists, The Magic Shop continues to exist today. I think without that run in the early '90s, this place would have gone out of business. But they came and made records that sound great — even now. Because of those records, I ended up having a business.

What a great development.

It was a lucky turn of the wheel. I had a room and people needed a room. I had a vintage Neve, and alternative bands and artists wanted to work on vintage consoles. They knew it was a fatter sound — more real, less processed. In those years, the studio became a home for great producer/engineers like John Agnello, Dave Sardy, Mitchell Froom and Tchad Blake. They helped start a run of about five or six years of great alternative rock, songwriter music, and blues stuff in the early-to mid-'90s. John and Dave continue to make records here. John just mixed the new Hold Steady record here this month. In a way it was similar to today, because the major labels were totally confused then as well. You always get the best music when the major labels are confused because when they're in control of the music and they think they know what sells, you get Britney Spears. When they don't understand what sells, then you can get fun stuff like Dinosaur Jr., Sonic Youth or Arcade Fire.

Something different or new.

Yeah, because they don't know what people want and they can't figure it out. The industry was flailing around then, as it is right now. They were flailing around because they didn't understand Nirvana. So they would allow things to happen on the margins — and it's the music from the margins that really is the interesting stuff. The music that stands the test of time is artistic, valuable and has some honesty attached to it.

From 2006 to 2007 was a big season for you. In 2007, you had three Magic Shop recording artists who were nominated for Grammys — The Klezmatics for Wonder Wheel, Keane for best pop vocal performance and Pink for best female vocal performance. In 2005, you won a Grammy for the Jelly Roll Morton boxed set. This year, you and Warren Russell-Smith just won another Grammy for Best Historical Album for The LiveWire: Woody Guthrie in Performance 1949.

It's an extraordinary nine CD set of the Library of Congress Recordings, recorded in 1938. I worked for months on the audio restoration. I got really lucky and won a Grammy, along with Anna Lomax Wood [Alan Lomax's daughter], Jeff Greenberg and Gateway mastering engineer Adam Ayan. The Library of Congress is an interesting place down there because, like all government offices, it is very confused. Every time we thought we had every version of a given Jelly Roll recording, they would find more stuff. At one point, they were taking records off the wall. Some people had actually put them on their walls as decorations! We were looking for the best copy that we could find of each disc. The way the library worked back in the day, if you wanted to hear Jelly Roll, you could actually go there and they would play you the original discs. Well, they obviously degraded pretty seriously over time. Luckily enough, they had made a number of copies. Ahmet Ertegun had even had a set made of the records, which he donated to the Library. I spent about ten days down there transferring everything to DSD [Direct Stream Digital]. We used the CEDAR Cambridge system for restoration. Fraser Jones at Independent Audio was very generous about letting us use CEDAR. It's a remarkable real-time restoration system that they've developed. I just can't say enough great things about it — it's more like a forensic audio tool. It lets you do things that you'd never even think you could do. In terms of commercial record releases, it's nice to have major label clients, and to have the albums get recognized. In the case of The Klezmatics, their record won the Grammy for Best World Music Record. It was recorded at LoHo Studios. I mixed at the studio with producer Danny Bloom. I think it's a vintage Neve record from start to finish. The irony of the Neve makes me smile. It is an old console that really seems to bring new life into people's recordings. This year, we won another Grammy for Best Historical Album. I, along with Magic Shop engineer Warren Russell-Smith, won for our work restoring a long-lost Woody Guthrie wire recording. The recording consists of 18 tracks of songs, stories and conversation with Woody and his wife Marjorie performing in Newark, NJ, in 1949.

What's your advice for people starting out small, at the project studio level — as opposed to the size and traffic of a studio like The Magic Shop?

You really need to diversify in order to make your studio successful. The days of depending on record labels are over. In order to have a commercially viable facility, you've gotta do lots of different things. It's so important for studios and studio owners to try and figure out different ways to generate income. This year, I just built a new room in my basement called The Red Room. It's for film mixing and restoration work. I'm sharing the room with legendary producer Elliot Mazer. I think people who are opening up small rooms can actually be more adventurous because they don't have as big an overhead. You can do low budget film scoring, music for videos, or band production — if you want to do that. Spec some time for a talented band that you see at a local club. One thing I really want to stress is that if you do this, is to make sure you have a signed agreement. I can't tell you how many bands have come to The Magic Shop and my assistants have spec'ed time to make a first record, and then the bands have gone on to become really successful recording artists — and my guys have gotten screwed. If something good does happen, you should be properly compensated in the future. After all, you are taking a risk on them! I try to pass on the skills and lessons I've learned over the years to the crew of great engineers and assistants we have here at The Magic Shop including; Ted Young, Brian Thorn and Warren Russell-Smith. You can also augment your project studio income with live sound work. Some engineers even discover that they prefer the live sound environment to that of the studio. There are certainly fewer, or at least "more reasonable" hours.

How does one break into doing audio restoration work?

I have an interesting suggestion for people. You should go to your local university. They will most likely have a collection of speeches, music recitals, vintage radio broadcasts, whatever. From time to time, these recordings will need to be transferred or worked on, and most of them will need to be digitized and preserved for posterity. For the major labels, a big part of their moneymaking comes from reissues, but established engineers and studios are already doing that work. My suggestion is to start outside the record business. Go find an archive. These things should be online. They should be digitized. Maybe you can begin to create a niche for yourself by digitizing an archive.

Let's talk about the state of the industry today. Where do you think it is now, and where do you see it going?

I think it's incredibly messed-up, incredibly damaged. I think this methodology they've created of merging companies and then firing half the people is a total failure. It's my hope, my deepest hope, that they will throw the music business back in the water and that these large corporations will realize that the music business is too small of a fish. It is not 1984 anymore; there are no more Michael Jacksons; there are no more CD reissues where they can sell the same record at $18.98. Throw the music business back to the musicians and to the people who want to create music that has artistic value — and music that has passion. Tell me any other business that's lost 40 percent of its market share in five years. This year it's down another 17 percent or something like that. I can tell you from a studio owner's perspective that the amount of calls to The Magic Shop is really down. But the labels confusion and ineptitude have created opportunities for people. That's why next time around Arcade Fire might have the number one record. It's times when the major labels don't know what they are doing that you really get the really great music. This is one of those times.

This may open the gates for up-and-comers.

The industry has fostered a fragmentation of the listening experience. And that's kind of a drag. I remember when I listened to the radio when I was a kid. I would hear Sly and the Family Stone, Ritchie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles; and then Laura Nyro. It was this big smorgasbord of stuff. Now, it's totally different. They've fragmented the audience by niche markets, because that's how they operate. There is more music being listened to now than ever before, though. I mean, I don't particularly like the American Idol style of music — it's too show-biz-y and Las Vegas-y for me — but obviously the American public is crazy about the idea of having people sing, and the idea of discovering artists. I think it's really funny that most of the new artists that major labels are supporting now are people from these American Idol shows. I see the destruction of the music business and it really makes me upset. I'm not only invested in it financially — I'm invested musically, psychically, socially and spiritually — in all ways.

Music as commodity versus music as music.

Well, they totally missed the boat with this digital delivery thing. Steve Jobs went ahead and created his own music business with iTunes. People are ecstatic about the way he delivers music to them. It's simple, it's elegant and it's easy to use. It's an incredibly frustrating thing, if you think about it from an archiving perspective. Think about how many records are in the storage lockers of these labels — how many incredible things that they just sit on! It's really silly, and it's just plain ignorant of them. They could digitize this unreleased material and sell it online — and make up some of the money that they have been losing! Bad choices, bad business practices, incompetent executives.

You were saying before that the reason you got into the studio business, or into music in the first place, was for the character of the people involved, and the relationships with and between those people. How do you think that translates into what's going on in music right now?

I think that good music and honest music are probably pretty similar things. It doesn't matter what the delivery system is, or whether it's metal or folk or jazz. The great artists are the ones who have made a connection with their soul — and then you are able to look into their soul with them. That is a connection that they have made within themselves, and then they've been able to translate that connection to you as the listener. It's about the passion of the artist. By '95 or '96, I had made a number of major label records in a row — like four or five of them — and I found the experience to be incredibly unpleasant. I didn't appreciate the interruptions and the constant looking over my shoulder. I thought it was really intrusive, unnecessary and counterproductive. I was lucky I started to get involved in the New York City singer-songwriter scene around that same time. I went to Café Sin-e [now closed] and saw a lot of new and unknown artists playing there. That's where I met my wife, Jennifer. It was a transformation for me. I got to hang out with people who were just beginning. I find that much more rewarding. Many of the records that people worship today are records that were made live in a room. People played and sang with the band — as a group performance. It was an event. It was a moment, as apposed to the modern way. "Okay, we'll go record the drums for five days and then we'll go and record this for 24 days and that for 19 days. We'll hope in the end that somehow, the space between the notes will add up to mean something — and that the connection between the musicians will add up to something." Sometimes it does. There are some people who can make incredible records that way. I don't know how to make records that way. The records that I produce — like Ollabelle, Sean Costello, Michael Powers and Jenni Muldaur — are the ones where I get people into a room and they go someplace. They feel something and we capture some sort of document — some sort of moment. It's much more of an Alan Lomax-type approach to recording.

Maybe that's why you're so attracted to doing reissues. It's preserving. It's archiving.

And it feels more genuine to me. It doesn't feel manufactured. It feels more like, "This is the best I can be at this given moment in time. Three years from now I may look back on it and say, 'Wow, I really sucked.' But at this particular moment, this is as good as I can actually make it." To me, there is value in that. I don't think it's a coincidence that people love records that were made in the early to mid '60s or early '70s. I think it has to do with the way those records were made. You listen to Joni Mitchell's Blue or something like that — it's just somebody talking to you. It's like she's sitting right there and she's saying, "This is how I feel today, and this is what happened to me." It's so compelling — as opposed to some kind of gussied up, over-edited thing.

What gives you a sense of purpose and drive? Is it your dissatisfaction with the industry — and wanting to do something about it?

I think it's this notion of retaining and celebrating musical values that are timeless. It's easy for these values to get lost in all of the stupid shit that goes on in the entertainment industry. It's kind of like a rollercoaster. You have moments where things are of spiritual, honest or emotional value. Then you have other moments in entertainment that are total crap. I think I got spoiled because I came of age at a particular moment in history when all kinds of music, no matter the format, were trying to achieve a simple but revolutionary idea — try to make the world a better place. It's a total fucking hippie cliché, and maybe my generation failed at making that happen — but we tried. We certainly tried. Maybe that's my curse for coming of age at that particular moment in time.