I first became aware of producer/engineer Tony Doogan by reading the credits on albums. I soon realized the same guy had worked with Teenage Fanclub, Belle and Sebastian, Mogwai, The Delgados, Young Knives and one of my favorite recordings, David Byrne's [Tape Op #79] soundtrack Lead Us Not Into Temptation for the film Young Adam. All of the records Tony has worked on seem to really have their own feel and presence — and they all sound great. I looked up information on him online and found out he'd worked for years out of the legendary Ca Va Sound in Glasgow and now co-owned Castle of Doom with Mogwai. It all seemed so far away and exotic to me until one trip to the UK, when I suggested to John, "Hey, let's go interview some folks in Glasgow." Tony's had some recent acclaim with albums by Canadian groups Wintersleep and Young Galaxy, and is in the planning stages for a new studio space.

How did you get your start in studios?

I was quite fortunate. The studio where I learned to become an engineer was Ca Va Sound, in Glasgow. It had a couple of rooms, one of which ended up a Neve room — an Eastlake-designed room. That was a good studio and a great place to start. I went to college for a year after school and then I got a job there as a runner making tea. That was the biggest studio in Scotland with the best equipment — a proper place. You got all the bands, producers and engineers coming in.

Do you feel that was a good way to learn?

Much better way to learn than, I imagine, going to college for four years. I think the college route is good, but I think you still come out needing to do a few years of the bare bones. We used to call them "Saturday bands". You know, they'd come in on a Saturday, do four songs and then you'd mix them and they'd be gone by eight o'clock at night. [laughter] They'd always be drunk by the time they finished. There'd be the guy at the back, the friend of the band who "knew about sound." Many days of that!

That was your graduation into recording?

That's what teaches you to work quickly and efficiently. I suppose the bad side of that is you have a whole set of "go to" sounds. "Here's the kick drum sound. Here's the snare sound." But that's what you have to do if you have two bands coming in one after the other. You've got to be quick.

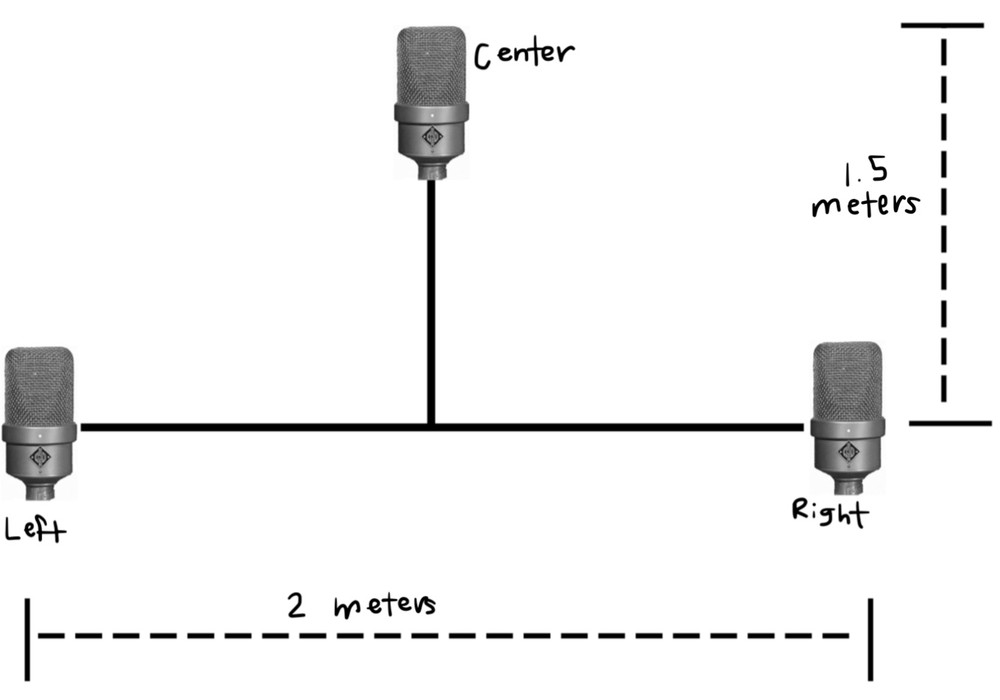

Did you ever leave the mics set up for the drum kit between clients?

No. [laughter]

I was always wondering if that was a faux pas.

I don't think so. I always thought it would be a great idea. Have everything set up and have triggers for the drummers — those kinds of drummers can never play consistently! I've worked with plenty of bands that have needed help and made them better. But great bands — you turn on all the lights and off you go.

When did you graduate from the "Saturday bands" then?

You never really quite graduate from them! One minute you're doing an orchestra in the big room and then Saturday afternoon you've got to go do a band in the rear room. I was doing bands like Teenage Fanclub and Belle and Sebastian, working on those records for months. But then you still have to go back to "Saturday bands". I think it's slightly unfortunate in the way I work now — I don't really get to do that. I only get to do sessions that are going to be commercially released, which is fine. I'm not mourning about it. But you don't have that, "I've got to get everything done in a day" kind of thing. I don't think I've done anything in one day in a long time. You should be able to go in, record a song and it's done. But then there's mixing, and then there's recalling the mix...

Punching in the vocal.

Yeah, with a different microphone! Then you've got to match it. Nothing really ever seems to get finished until you get it back from the mastering.

You moved up from assistant engineer and you started getting co-production credits with some of the bands. Who were you learning production from?

Ca Va was a large studio and Scotland had a lot of big bands like Wet Wet Wet, Hue and Cry and Deacon Blue. All those bands used to come record at Ca Va. You were fortunate that there were lots of good producers like Jon Kelly. Mick Glossop came through one time for a month and scared the living daylights out of me. In retrospect, he was just being kind of the way I am. If something doesn't work I'll go, "That's not the way it should be!" I want it to work while I'm here. If you plug a mic in and the jack's hanging...