Al Kooper's musical resume reads like a rock and roll version of Where's Waldo. Sometimes he's right there staring at you, other times you have to sleuth around to find him lurking in the shadows. But somehow the guy seems to show up on nearly every page of rock history.

Ticking off Al's career highlights is akin to making a "Tape Op readership fantasy career wish list." Boldly crashing a 1965 Bob Dylan recording session and ending up playing the signature organ lines on the Highway 61 Revisited album as well as Blonde on Blonde? Check. Founding probably the first horn-based rock band — Blood, Sweat & Tears — thereby ushering in a new type of pop/rock? Check. Discovering one of the top bands of the classic rock era — Lynyrd Skynyrd — and producing, mixing, and playing on the perennial arena rock anthem, "Free Bird?" Check. Playing with Hendrix, the Stones and The Who on Electric Ladyland, Let It Bleed and The Who Sell Out? Check. Producing nearly a score of high quality solo albums with full artistic control, most of which were bequeathed very generous budgets, which are then used to hire some of the modern era's most talented musicians? Check. Being given one of Jimi Hendrix's guitars by the man himself? Check. Discovering The Zombies' nearly shelved Odessey and Oracle album and convincing the label to release it in the U.S., thereby unearthing the potentially lost "Time Of The Season"? Check. Producing The Tubes' "White Punks On Dope"? Check. Writing what is arguably the most entertaining musical autobiography (Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards)? Check. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

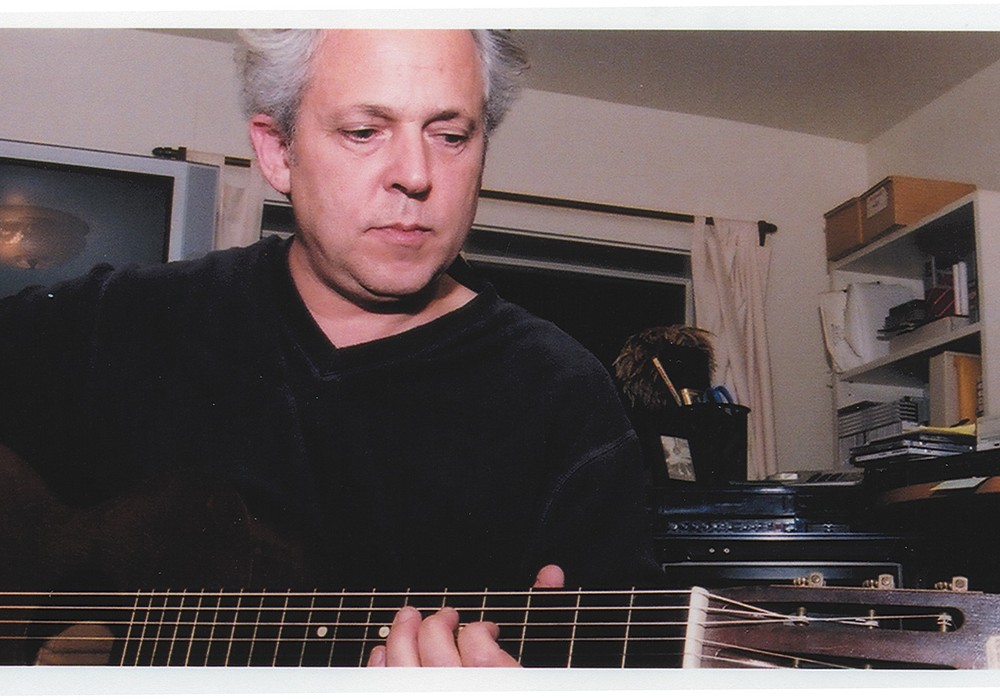

Starting in the late 1950s, the multitalented Brooklyn native set about making it in the music industry with an intensity and ambition few others could ever claim. From his teenage tenure as a guitarist in The Royal Teens ("Short Shorts"), to co-writing "This Diamond Ring", to a teaching position at Boston's Berklee School of Music up until 2001, Kooper has not slowed down much at all. When I met with him at his Boston-area home, he was just coming off a slew of solo shows and preparing for a tour of Japan with his current band, The Funky Faculty. A gracious host with deadpan humor in spades — when I asked if we could take some photos during the interview, he demurred, "My hair won't look good for days." Al showed me around the house, including a tour of his studio, Subterranean Homesick Studio in the basement (of course) and played me numerous remastered selections from his recently released solo career retrospective album 50/50.

I read your autobiography a few years back, and one of my favorite bits is the story of the Jimi Hendrix Stratocaster.

Well, basically he gave me one of his guitars when I played on Electric Ladyland. He wanted to give it to me at the session. I told him he was crazy and, "No." And he said, "Why?" I said, "It's your guitar. What are you giving it to me for?" The next day he had it delivered to my house by his roadie, so I said, "Okay!" Then I had to do stuff to it so I could play it. I had guilt pangs about that. I had it for about 22 years and I sold it in 1991, because people were breaking into my houses in two cities. I made a big noise about selling it so that they would stop breaking into my house.

Did it work?

Yeah. I sold it for $100,000. I knew that if I held onto it, it would hit the million mark, but I couldn't have it around anymore. It was a magic guitar, but I was glad when it went, and I was glad to get that $100,000 for a piece of wood with six pieces of wire on it that I didn't pay anything for.

[laughter] Earlier we were talking about hard drive crashes. Tell me about your film score that crashed.

It was a film I did about four years ago and the director is a friend of mine — Peter Riegert — he's a character actor, or as Dr. John says, "A char-actor". He was in Animal House and Local Hero and a whole bunch of movies — Traffic - and this was his first feature that he was directing. We did a short together, which was the first thing that he directed. It was nominated for an Academy Award so I figured we'd stick together. We actually had a Blake Edwards/Henry Mancini deal — every film that Blake Edwards directed, Henry Mancini did the score. This was Peter's first feature, and initially he started out with a lot of music in mind. So I did all this music and the hard drive ate it — I didn't have it backed up. I'll tell you though, redoing it wasn't as difficult because it was current and it was in my mind. I got it back pretty fast. After I got it back, the producer talked him into using as little music as possible in the film. [laughter] So hardly any of it actually got used. That's what happens when you score films.

Redoing of it was kind of as if you had done fancy demos?

Well, it was instructional. Film scoring requires a whole other head. If you're a great musician and a great composer, that does not guarantee that you're going to be a good film scorer. It takes me two weeks of writing fake cues to warm up for it, because you have to be fluent in breaking rules in order to do the job properly. I am so versed in rules that it's very difficult for me to get in that head, but I can do it. Also, you have to be totally unemotional about what you write, because film directors are notorious for not understanding film scores. So it's a tough one.

How did you learn about syncing to cues and all?

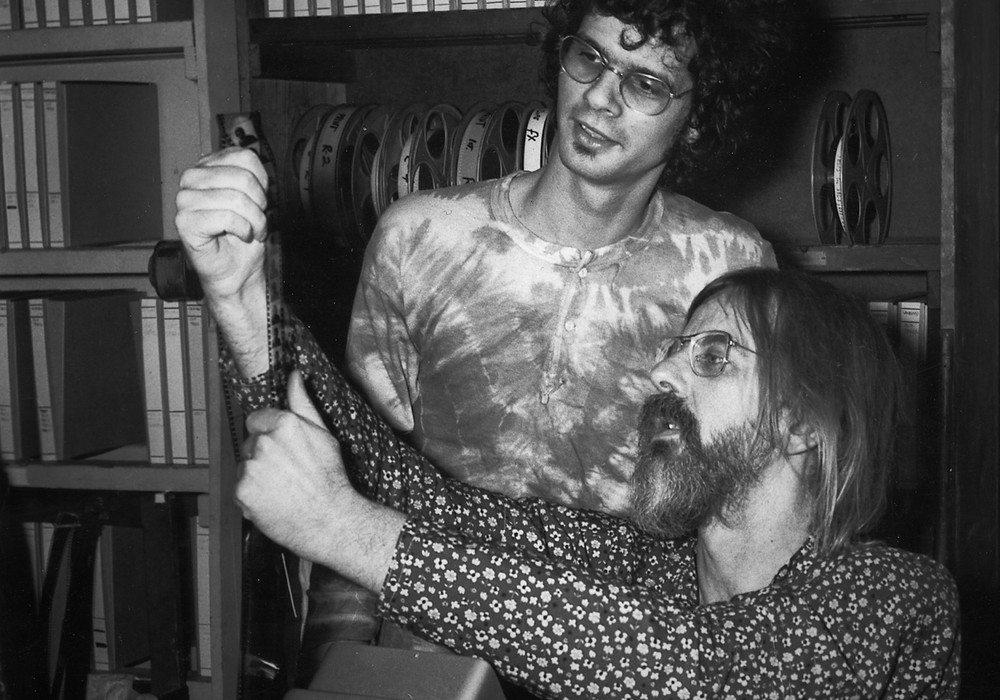

The hard way. I scored my first film [The Landlord] in 1969. There were no computers back then, so I had to do it by hand. The producer of the film, Norman Jewison — a famous film director himself — interviewed me when the director picked me, and he was horrified. I was sitting in front of his desk with the director, Hal Ashby, and he said, "Have you ever scored a film before?" and I said, "No." He went, "Ugh," and then Ashby kicked me and whispered, "Just go along with this." He was not very happy about the choice, but I actually limped my way through and that really prepared me for going ahead. But as you do it, you learn so much more. If I had to give...