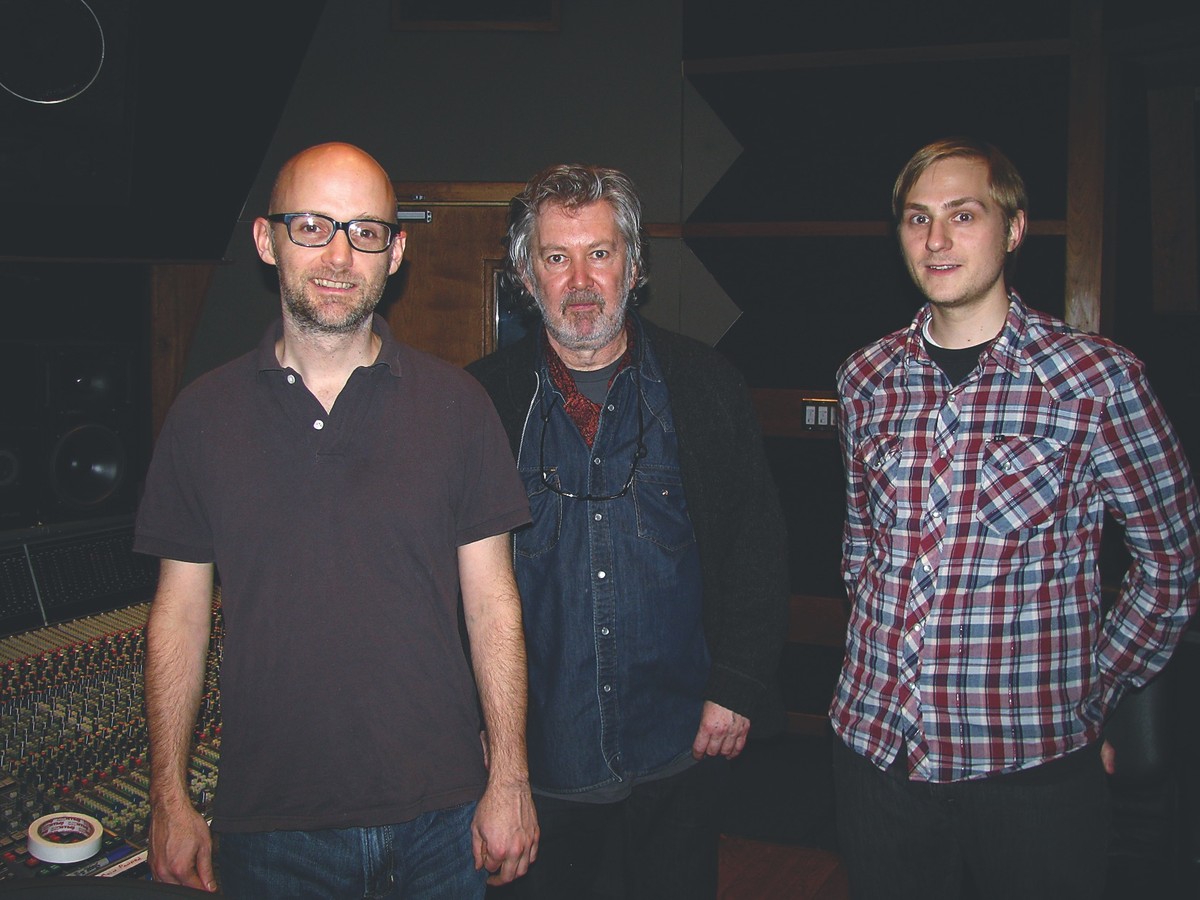

Andrew Marcinkowski has been working as an engineer in some of NYC's best known studios for ten years. In house stints at Chung King Recording Studios and Mission Sound have gotten him a great reputation around town, and he's now doing freelance work both in New York and in the greater Boston area. He was willing to offer some insight into what he brought to the table on Moby's latest release.

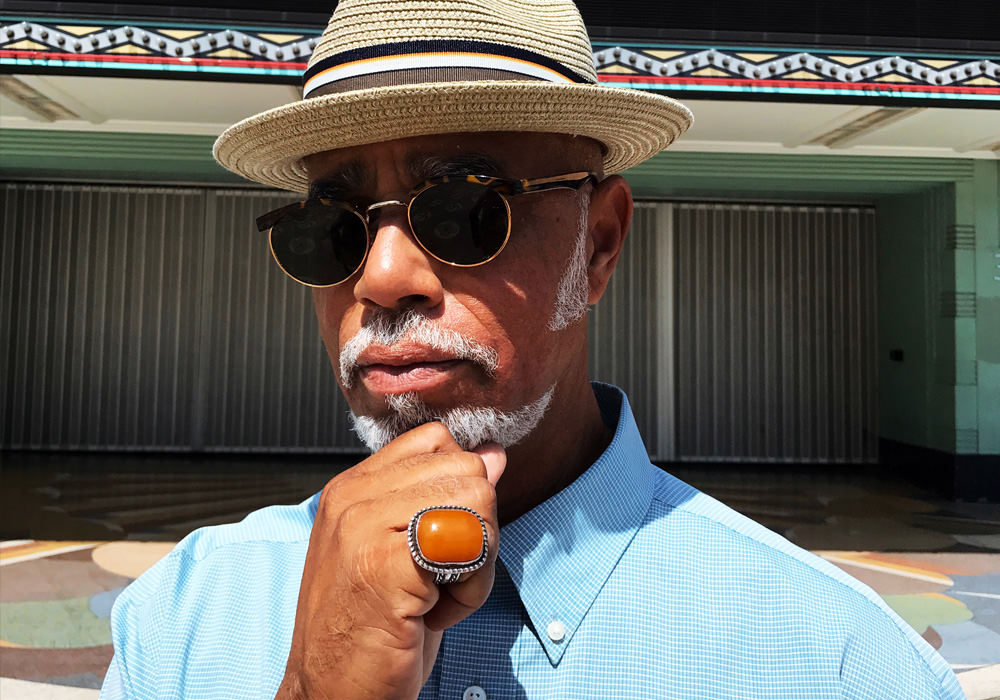

Moby's apartment in Little Italy is simple, clean and economical. Framed gold records adorn one large wall, with the only other décor of mention being a well-organized, sizeable collection of vintage keyboards and synthesizers. His furniture and fixtures are clean and uncomplicated, and the whole place comes together not unlike a meditation hall — serene, peaceful and relaxing.

It's on a warm spring day that I meet him here, and I follow Moby and his publicist up a flight of stairs to a small, private deck on the roof of his apartment building. His publicist squirms and screeches as two bees fly over her head, but when they move on to dive-bomb Moby, he sits there nonplussed. "They won't sting. They're probably just having sex or something."

We're here to talk about the production of his new record, Wait For Me, a mournful, atmospheric look inward that is quite a departure from his last two albums — 2005's pop collection Hotel, and 2008's homage to the dance floor, Last Night. With Hotel Moby wanted to make a very pristine sounding record, something that was immediately commercially viable. "I'm ashamed to admit that's what was going through my head." And after Last Night's rave reviews took Moby deeper into the world of red carpets, MTV appearances and alcohol consumption, he knew he didn't want to pursue commercial success anymore. "I wasn't very good at it and I don't like that world very much. Creativity in and of itself is beautiful. A record shouldn't be judged by how much it's sold, but by how it's affecting people emotionally."

It was with this intent that he abandoned the big, professional tracking sessions that had led to his recent works, and chose instead to make a record in his simple home studio, a single 12' x 10' room with a Pro Tools rig and some preamps. "When I recorded Hotel, I really wanted to record everything the 'right way'. Everything was recorded flawlessly. Unfortunately it had very little character."

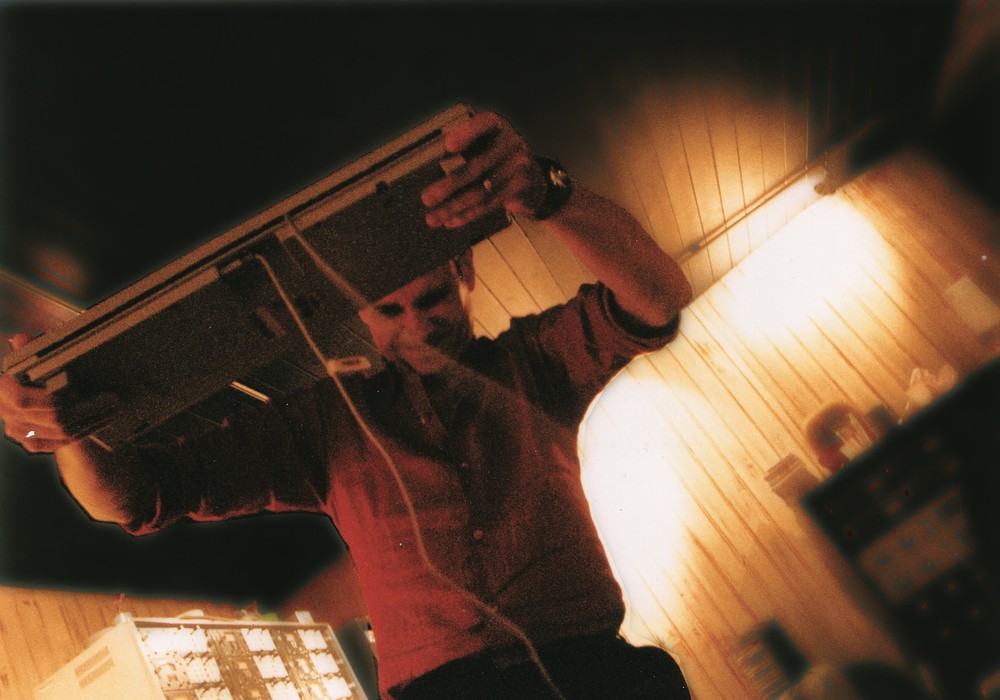

The very same ease that marked Moby's response to the bees carries over to his engineering work, when he shows me some of his mic'ing techniques. "The key to a good sounding record is the sound source, the microphone and the preamp. I can do that in my closet. Want to see how I record my kick drum?" He nonchalantly sticks a Shure KSM27 in front of his kick drum, with little regard for a specific placement.

There seems to be a trend in the recording industry in which every frequency is used simply because it can be. A marketplace flooded with affordable microphones and an endless array of plug-ins has led many an engineer to pump up the entire range of sound of a recording, bringing everything to the front of the speaker and confusing the size and proximity of a sound with the presence. "I was mixing a friend's record and they had twelve microphones on the drums. It wasn't coming together, so on a whim I took out all the close mics and it suddenly sounded like an instrument." The same KSM27 Moby used for the kick drum? He haphazardly moves it up two feet, achieving his overhead drum sound.

Moby's been making records since he was a teenager, and has learned to rely on the tried-and-true tools for the job. His mic locker is tiny, consisting of a pair of the KSM27s, a recreation of an RCA ribbon mic and some Shure SM57s. His preamp collection is also primitive- yet-effective — "I've got a couple of Focusrites and four Chandler EMIs [TG channels]. I find a few things that work for me and just stick with that." Yet he's wary to rely on a formula that's not working, often supplementing a live kick drum with a programmed kick. "I'll let the drums exist as a mid-range instrument, and let the programmed drum handle the low stuff."

It's easy to form an image of Moby, or for that matter, most electronic musicians, as control freaks, twiddling knobs and dials all day in a tiny room and manipulating every sound to...