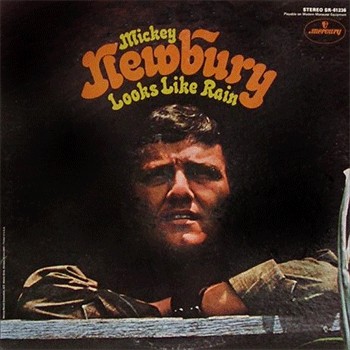

Last fall, the Magic Shop's Steve Rosenthal [Tape Op #66] and I restored and remastered Mickey Newbury's Looks Like Rainfor the four CD box set American Trilogy, released in May 2011 by Drag City. I'll come right out and confess that when I finished the mastering and sat down and listened to the whole thing, it literally moved me to tears. The second to last song, "San Francisco Mabel Joy," ends with a swelling, angelic choir whipping through a Leslie cabinet and a heartbreaking final line. (I won't spoil it). Then it dissolves into atmosphere, a rainstorm, wind chimes.

You might know Mickey Newbury best for writing hits like "Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)" for The First Edition (with Kenny Rogers on vocals) and "American Trilogy," famously covered by Elvis Presley. The Nashville singer songwriter was a contemporary of Kris Kristofferson and a brilliant and prolific songwriter. He also was way ahead of his time when it came to studio production, most evident on his 1969 release Looks Like Rain, which he recorded with engineer (and very busy session guitarist — he played the guitar riff on Roy Orbison's "Pretty Woman") Wayne Moss at Wayne's Nashville studio, Cinderella Sound.

When Steve and I pulled up the original stereo master for mastering, we discovered we had a damaged safety copy, riddled with dropouts and wow and flutter. Luckily, we also had great sounding 96 kHz / 24-bit transfers of the original 2-inch, 16-track analog master. So Steve and Magic Shop engineer Brian Thorn remixed, or, really, recreated the original stereo mix by reverse engineering it from the multitrack.

Curious about this process, I spoke with Steve, Brian, and Looks Like Rain's original recording and mix engineer Wayne Moss about creating and recreating Mickey's epic album.

Steve, you and I decided the stereo master, most likely a third or fourth generation safety, was unusable. How did you convince Chris Campion, the box set producer, that we needed to recreate the stereo mix from the 16-track master?

Steve Rosenthal: We didn't have to do much convincing. You only get one crack at these reissues, and since this was our chance to do the right thing for Mickey Newbury, we all agreed pretty quickly that we needed to remix.

You had already done this with bonus tracks on the reissue of The Rolling Stones' Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out! and with Sam Cooke at the Copa, basically recreating the sound of the original master.

Steve: It's a tricky thing. You're dealing with people's sense memories when you are remixing and recreating mixes from the '60s and '70s. These songs have been played so many times, and people have a deep attachment to that sound, so you have to respect what happened when the record was made. You need to be aware of the history of the mix and the technology used during mixing.

Wayne Moss: We used a 16-track MCI tape machine at 30 ips with just some limiters and Telefunken mics, U67s, one on Mickey's vocals and one on his guitar. And of course Mickey's genius.

How was it working with Mickey?

Wayne: With Mickey, we'd do something almost perfect, and he'd say, "Well, I messed something up on that one spot." I'd ask him if he wanted to cut over that, and he'd say, "What's the danger in cutting over it?" I'd tell him, bleed through. If it didn't erase properly, part of the old cut would still be there. Consequently, we went through a whole lot of tape on that session.

I tracked down a mint copy of the original vinyl and transferred it to Pro Tools for you to reference. How did you break down the different elements when you started to reverse engineer the mix?

Brian Thorn: The first thing I did was line the up the vinyl transfer with the multitrack transfer in Pro Tools. Having the vinyl mix patched to a tape return made it easy to switch between what I was doing and the original mix. I started by getting some rough levels and trying to emulate the panning. Then I concentrated on the EQ and compression of the individual instruments. For EQ, I used the [Neve] console's 1079s, but I also used an old Focusrite ISA 110 to take some of the low mid build-up out of the vocal and a Sontec to take the boom out of Mickey's acoustic guitar and add a little clarity.

Clearly this was not the first time you've had to reverse engineer something.

Brian: In these days of smaller budgets, producers and artists sometimes forgo documenting mixes in favor of using the time on another song or another mix. On many occasions, I've had to recreate mixes without recall notes.

I remember you telling me about getting the levels of the chimes just right.

Brian: Those sound effects tracks would come in and out throughout the record. I used both Flying Faders and Pro Tools automation to get the levels and rides to match. One thing that struck me: as I was listening in the headphones matching the levels at the start of a new tune, I heard one of the tracks slowly sweep across the stereo field from left to right as the volume grew and then fell. It made me think about the fact that when this mix went down in 1969, they were sitting there with their hands on faders and pans, performing.

Wayne: We'd have as many as six hands on the console at the same time. My two, Mickey's two and [mix engineer] Charlie Tallent's two, doing pans and adding echo to the train to make it sound like it was going off in the distance.

Brian: Here I am 40 years later drawing a line in a computer.

The technology's an interesting point because for the remix, you guys had access to a lot of the Magic Shop's gear that was around in the 1960s when Look Like Rain was originally recorded, but you had lots of new tools too.

Steve: Our console [a custom wrap-around 56 input Neve 80 Series] was built in 1970 and commissioned in 1971, but is has a similar tonality to desks that were being used back then. That's the main thing that helps when we do these recreations and mix vintage material, working with this vintage class-A console.

Looks Like Rain is drenched with reverb and atmosphere. All the songs are connected by sounds of rain, trains and chimes, so recreating that reverb was a crucial part of the remix.

Brian: I listened to the record and felt pretty certain it was an EMT plate. It just had that classic sound. Steve spoke to Wayne who confirmed he had used an EMT plate on the vocal. I used the Magic Shop's EMT 140 predominantly on Mickey's vocals and EQ'ed both the send and return of the plate to get it to sound as close I could to the original mix. I should also mention that all the Leslie reverb-y vocal stuff was printed to one of the 16-tracks. Obviously this was a huge help.

Wayne, whose idea was it to run the choir through the Leslie?

Wayne: It was Mickey's. I found the best way to get along with Mickey was just to do whatever he wanted. That's why I have crickets in my echo chamber to this day. He wanted to record crickets, but they wouldn't chirp in their container, so he said we ought to shake 'em loose and let 'em run around a bit. They're chirping to this day.

I read somewhere that the ambient sounds were added to mask tape hiss between tracks from all the overdubbing.

Wayne: We didn't have any tape hiss because we were cutting at 30 ips. The rain and the train were just things Mickey wanted to set a mood with. The album that we got some of the rain and train sounds from is One Stormy Night by the Mystic Moods Orchestra.

Did you or Mickey just have a copy of that album laying around?

Wayne: Mickey had it. He had a houseboat, and he liked to go out in the middle of a rainstorm and put the boat in a circle and listen to it rain, going around in a circle in the middle of the lake where he wouldn't run into anything. It helped him relax and write songs.

That's a beautiful picture, and having spent so much time with Mickey's recordings, I can totally imagine it.

Steve: It's a cliche, but this record was very ahead of its time — very conceptual and very artistic. You listen to it from beginning to end and you get transported.

Capturing that mood and preserving that atmosphere was a huge part of our approach to remastering all of Mickey's music for the box set.

Steve: Exactly. If we do our job right, we don't call that much attention to ourselves. If the record remains in the time and space that people believe it should be in, then we've been successful. If we do our job right, we become transparent.

_display_horizontal.jpg)