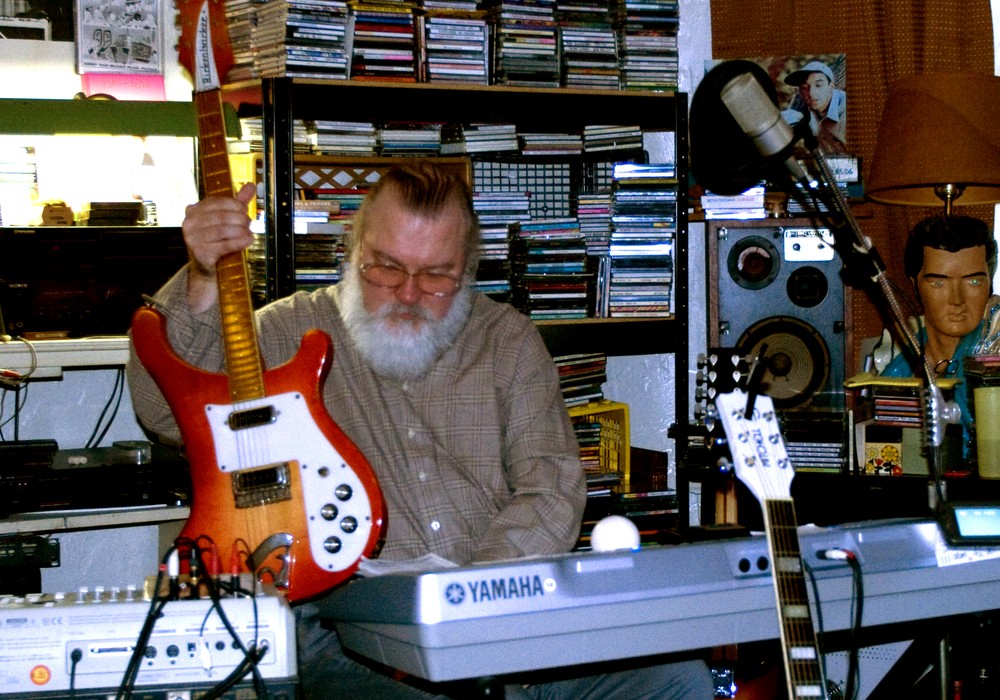

It's easy to play a "six degrees of separation game" with an engineer-producer who's worked with the likes of Joe Pass, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt and Vince Gill. Rather than tout his resume, however, Ed Eastridge refers to himself as "a musician who knew how to engineer." In his eyes, that approach will serve anybody wanting to learn about recording: "They should be doing it themselves, anyway. It's just an extension of being a musician, and all the tricks of the trade are becoming so much easier." Eastridge developed his philosophy during many lengthy nights with the late Danny Gatton, known among fans as "The World's Greatest Unknown Guitar Player" — which he earned through lightning-fast, dizzying chops, and an unlikely blend of country, jazz and rockabilly playing. All through the '80s and '90s, Gatton's exacting approach to recording typically happened in the unlikely confines of Big Mo, a truck Eastridge originally designed for live remote work.

Nonstop hours were the norm in this environment, yet nobody could argue with albums like Unfinished Business (1987) or Relentless (1994), a team-up with organist Joey DeFrancesco. No matter who played what, there was always something to learn at a Gatton session. On Relentless, for example, "Joey showed me some cool stuff — how to get a direct signal out of a B-3 [organ]," Eastridge recalls. "Also, you get a really nice bass signal off it, a lot more presence than you get [from] mic'ing the bottom of a Leslie." With Gatton, Eastridge focused on multiple inputs to boost their options during the recording process — usually by focusing on two amplifiers and a direct signal. "If we were unhappy with either of the amps we could send the direct signal back out to the live room, and just have it going through another amp and be re-mic'ed for the mixing session," he said. Not only did he learn plenty about recording from Gatton, "I learned a lot about guitar, too," Eastridge said. "I don't play anywhere near as well as he does, but I did learn a lot about music from him."

The road to Big Mo began during the late '70s. Feeling a desire to branch out from playing guitar, Eastridge had started hanging at Track Studios in Silver Spring, Maryland — where he did amateur projects for friends. When he decided to take the plunge, Eastridge originally envisioned using nothing more than a 4-track recorder and a small, homemade console, until an objective survey of the studio scene convinced him otherwise. "I figured, I couldn't really compete with 'real' recording studios, 'cause there were a lot of 'em in D.C. that were pretty well established, so I thought I'd build a remote truck," he said. With help from friends, Eastridge built a 24-track console, and bought an old Ford F-6000 newspaper truck. (Incidentally, the "Mo" in Big Mo came from a friend who gave Eastridge an interest-free loan that took nearly a decade to pay off.) "Shortly after we got it finished, I was on my way to the gig," Eastridge recalls. "I blew the engine and had to get towed to the gig, which is always fun... I remember the tow truck driver saying, 'Oh, yeah, my daddy loves these, he calls these 'grenade engines'. 'Great, thanks for that little [aside]!'" Eastridge rebounded by buying a Mercedes truck — "And we just lifted the box off the chassis and stuck it on there around '89 or '90," he said.

The changes prompted Big Mo's first major renovation at the hands of John Storyk, who helped Jimi Hendrix in designing Electric Lady Studios. "He didn't charge me too much money," Eastridge said. "A truck is hard, because it's small, and you've got to have a lot of wire, and there's just not much room to do stuff." Once the renovations got underway, Eastridge bought a Sony APR-24 console from Greg Lukins, which weighed a good 800 pounds. "The console was actually built in," Eastridge said. "The walls and the acoustic treatment were built around the edges of the console, so it came right to where the faders were." Eastridge also got Dolby SR noise reduction for his tape machines. "It was 24-channel, so we would encode each tape that was recorded — it would automatically switch," he said. "I still think there's nothing that touches that sound." For mic'ing, "I used the same ones that are still popular," Eastridge said, including AKG, Neumann and Sennheiser. He especially liked the AKG 451 — "they're just little pencil mics we used to put on almost any acoustic stringed instrument, and it would sound great," he said.

Eastridge also felt partial to the AKG 535 and Sennheiser 431, which helped greatly for isolation recording. "You could have a lead singer standing right next to an incredibly loud kit of drums, and a bunch of amplifiers and you couldn't hear anything but him," Eastridge said. "It makes the drum sound a whole lot better when there's not a lot of bleed."

The Big Mo trucks changed hands in the late 1990s, when Eastridge sold them to one of his engineers, Greg Hartman, and the owners of Entertainment Sound of Silver Spring, Maryland (Ed Casey and Patty Hecht). Greg Hartman continues operation of the trucks in College Park, Maryland.

The Big Mo name also survives in the label that he runs in rural Vermont with his wife, Dixie. Although the Danny Gatton reissues are Big Mo's focus, its roster also includes blues and roots musical artists like Rod Piazza and Johnny Neel. When the Gatton reissues started, Eastridge found himself dealing with the realities of a digital world. He'd actually started shortly before selling off Big Mo, when he built a second, smaller digital truck. "It had eight Tascam DA-88s in it so we could do dual 32-track [recording]," he said. "It had a Mackie console that we used primarily for monitoring."

These days, Eastridge's main working tool is Nuendo — a recording software package that he'd seen his stepson Justin Galenski using. "He dragged me into this digital world kicking and screaming... 'No, no, don't make me do it!' But when we started he had a Roland 18-channel all-in-one recording box, and he let me record my solo guitar CD on that. And I said, 'This isn't bad!'"

Like many people who grew up working in an analog era, Eastridge prefers analog, but believes the ease and convenience of digital formats won't push today's generation to go backwards. "If you talk about how things were done in that '80s [and] '90s world, they look at you with bug eyes: 'You did all that? For what?'"

Eastridge and Galenski also serve as the creative team for Holly Gatton — Danny's only child. Holly created the Flying Deuces label to preserve her father's legacy, which has only continued to grow since his death in 1994. The label's first release, Funhouse, is a live recording of Gatton's eight-piece band of the same name, which also featured a four-piece horn section. Eastridge recorded the performances with engineer Ron Freeland in June 1988. As far as Eastridge is concerned, the biggest boon from a digital setup is ease of editing. He points to his postproduction on Funhouse: "Every song had four or five choruses of tenors, trumpet and/or trombone. Editing these lengthy takes down to under eight minutes took a considerable amount of editing. It really took a long time to create believable edits because everybody's trying to play something totally different [on] every chorus."

Eastridge has also released a CD of his own, Music From The House With Four Chimneys. He's conceived the album as an adaptation of compositions by the French composer Erik Satie for solo and duo guitar, with occasional accompaniment on accordion and sax. "Some really nice guitar recordings may help spread the word on Satie to other guitarists," Eastridge said. "I think he was a great composer, and I'm fascinated by him as a person."

For the immediate future, Eastridge sees himself doing less recording — mainly, because of his commitments to running the label, teaching guitar and playing live music himself. He's not ruling out the odd remote session, "But it's going to be a deal where I just go down there and supervise," Eastridge adds, "Do the easy stuff: 'Okay, you guys run all the snakes, and set up all the mics.'" Live remotes will remain a different story from digital studio sessions, "because you've got to put out a million feet of wire, no matter how you cut the cake," Eastridge said. "The truck's still gonna be outside, and the stage is still gonna be inside." The same logic drives Eastridge's fondness for live music, "because of the energy, mostly, and the fact that you can't fake it — you actually have to know how to play your instrument," he asserts. "There's no bullshit in a live performance."