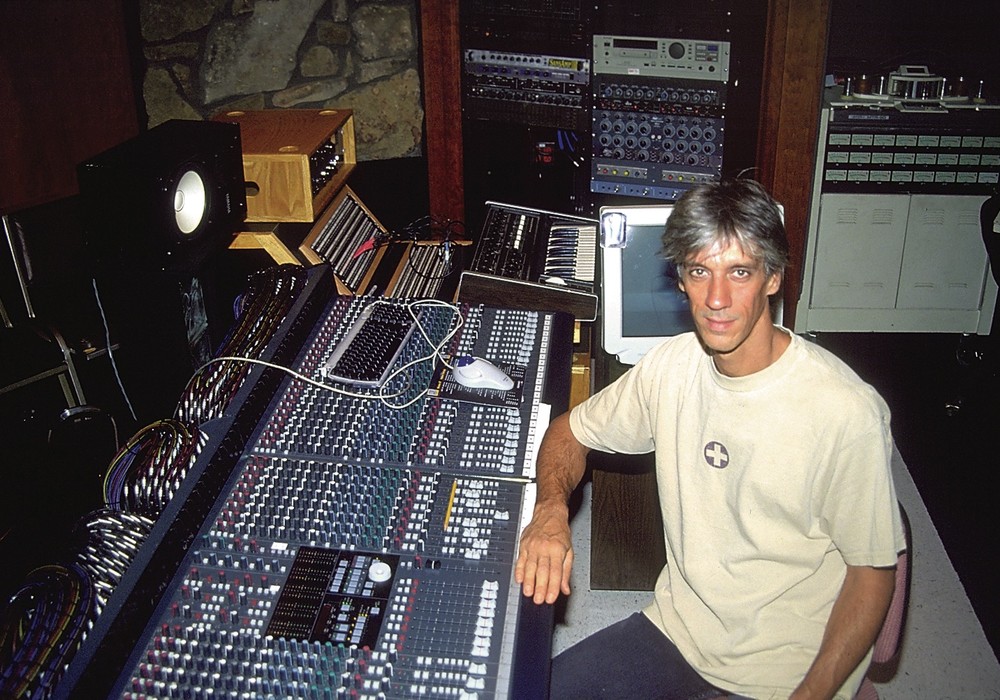

Queens, NY, native Greg Calbi has stood atop the musical food chain since the mid-1970s when he burst onto the scene mastering monumental albums like John Lennon's Walls and Bridges and Bruce Springsteen's Born to Run. Nearly 40 years later Calbi, (along with his fabled company, Sterling Sound), still has his pick of the recorded litter. Recent projects include Bon Iver, Fleet Foxes, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon and countless others. Following a recent session with Calbi to master my new album, I sat down with him to talk about his storied sonic legacy.

For a guy who's associated with some of the most renowned albums in history, rumor has it you never planned on a career in the music business.

I had gotten a Master's Degree in Communications from UMass in 1972. I came back to New York hoping to be a documentary filmmaker, either at one of the networks, public television or radio — anywhere I could continue on the communications path. One night at a party, I met a guy who worked at Record Plant Studios. I was a huge music fan at that point — I played guitar and had been in a couple of bands I was totally intrigued. He told me that occasionally they needed people to help with remote recording. So I said, "Listen, if you ever have any work, I'd be interested." At the time I was selling shoes in Flushing, Queens. About a month later, the guy called me and asked if I knew how to drive a truck. I had done a lot of construction work in college so I knew how to do it. He told me he needed someone to drive a truck down to Duke University to record Yes on the Close to the Edge tour. That's how I got into this business.

Did you do anything on that gig besides drive the truck?

I carried wires up to the stage and back, and broke stuff down — putting mics and other things back into their cases. Basically grunt work.

What happened when the gig was over?

One of the engineers on the truck said, "Hey, you should come around the studio sometime. They need guys to help out." I said, "Hey, I'll do anything. I love music." I didn't expect it to turn into anything; I was just thrilled to be involved in music and recording. Things grew out from there. I got a job in the studio as a general assistant. We had a lot of jingle dates [music for advertising], so I had to put the microphones out for the engineers. I learned about mic placement from setting up sessions for the engineers to tweak. The people working there at the time were a huge amount of fun.

Who was working at the Record Plant with you back then?

When I started it was Jack Douglas, Jay Messina, Shelly Yakus as well as Jimmy Iovine, Thom Panunzio, David Thoener, Dennis Ferrante, and Rod O'Brien, who were all assistants. It was a fantastic group of guys. Some of them were more receptive than others to teaching me, so I had to basically pretend I knew how to do things in the studio. I remember one time I was alone with Todd Rundgren on a session and he asked me to patch in a Teletronix [LA-2A], or some other piece of gear. I said, "I don't really know how to work the patchbay." He just stared at me, like he couldn't believe what I was saying. I truly knew nothing. But little by little, I would come in on the weekends and learn from the other assistants.

How did you get into mastering?

My late friend Tom Rabstenek had taken over the cutting room at the Record Plant after only about a year of experience. George Marino, who's been with me here for 35 years, left the cutting room to go to Sterling Sound. Tom was left with a stack of cutting notes for some phenomenal albums, like Stevie Wonder's Innervisions and the Allman Brothers — he had to cut lacquers on from George's notes. Tom couldn't do all the mechanical changes by himself because everything was done by hand back then; from changing EQ, to moving the fader and running the lathe. Tom was going crazy by himself, so I would go up and help him.

Did you have any idea how to cut lacquer at that point?

He showed me. He would say, "For this EQ, you turn this to +2, then after the song is over you put it back to zero." So I would do that. Then he would say, "Move the fader here, and run the machine here," etc. So the two of us were...