In issue #15 we ran a rather brief interview with Liam Watson about his London-based Toe Rag Studios. In the following 12 years I always remarked that Tape Op needed to revisit Toe Rag and chat with Liam again, as his profile has only grown larger with well-received albums by The White Stripes and James Hunter coming out of this 8-track, analog-only, retro-leaning (and looking) studio. So revisit we did, and Liam proved to be a lively gentleman. His studio was nothing short of fascinating; it is a special place, one that engenders a different way of working. Liam's attention to songwriting, playing, vibe and feel puts him in a classic producer's role. Toe Rag has seen sessions by Billy Childish, Hugh Cornwell, The Cribs, The Datsuns, Holly Golightly, The Kills, Madness, Pete Molinari, Supergrass, The Ettes, The Television Personalities and The Zutons come through its doors. Many more are to come, for sure.

Larry Crane: You started with a quest to figure out how older records were made.

It was quite an eye-opener doing my first sessions on the 1-inch, 4-track. It really started to make a lot more sense about some of the things that I'd been listening to. Not quite understanding, "How did they get that like that? They only had this. I've got eight tracks and they only had three or four. And it's like go onto to the 3- or 4-track machine and you see...

LC: It's pretty interesting...

Yeah! It's really interesting! And quite shocking in some respects.

LC: I had a conversation with Charles [Thompson] from The Pixies, and he was doing those Frank Black records live to 2-track for a while. I said, "Those sound great! How do you like it?" And he goes, "I love it! You get a good take, you walk in and listen and you're done!"

And it sounds good!

LC: All it needs is mastering! And he said, "But my bandmates hate it! They always wanna fix something."

Well, this is another thing that I find a little bit frustrating — I mean, you just said it there. I've had experiences where I've been with bands... About four or five years ago a band came in — they were from another country. They came in and we did two songs in a six-hour session and it was great. Do a live backing track, overdub the vocals, some percussion, a solo — really simple stuff. They went on and they got signed by a major label, and we ended up doing an LP together. One guy in the band wanted to go to a posh studio — he wanted to keep it analogue, but he wanted 24 tracks. I said, "Why?" And he said, "Oh, we've got all these ideas and..." I like the band, and everyone else wanted to do it, and I just thought, "Well, fuck it! This will be an experience. I'll just do it." We did it in RAK Studios; a very nice studio and lovely people. We did it 24-track and it took a long time to do. It was a very interesting experience. The reason why we did it was because this guy — the guitar player — he wanted to have the rock-star treatment. He wanted to have seven tracks to overdub the different guitars. He wanted it to take a long time. And he wanted to live the dream of taking two months to record an album. He wanted that experience because he had worked for it all his life, and he had read about this. He wanted to be involved in that. I was interested to see how it was, and it was an interesting experience, because it was alright. We had to go to different studios to mix and we did this and that. But it's a very long-winded way of doing something when really there was no reason to do it like that.

LC: How did you feel when you compared the final versions?

The first single was a re-recording of one song I had done here in three hours. And you know what? It wasn't as good as the one we did in three hours. It's the one that got released. Maybe, it was a bit beefier sounding, but you know what? Mine didn't even get a re-mix. Of course I could have beefed it up a bit. But mine was mixed in 10 minutes, and it wasn't night and day. It was that sort of level of "what's the point?" So, that taught me quite a lot. One of the B-sides of the first single was the other track that we did here. When it went to the mastering engineer he was, "The fucking B-side sounds much better than the LP. Sounds MUCH better." The artist wanted to go through that procedure. It's not something I would do. I'm very much aware that what I'm doing is for the artist; it's not my record; whether I'm producing or whatever. It's their record — they have the final say. I can only give them advice, and if I have an opinion, and I think it's needed, I can give it to them. Whether or not they take that is another thing. I would actually never rule out recording in another studio if I thought it was really worth it, but I'd really think twice about doing it just to satisfy somebody wanting to do something for the sake of because they hadn't done it. It's just a slightly negative situation in some respects.

LC: Yeah, it sounds like a lot more work for not much gain.

I mean that's another reason why technology went the way it did, in some respects, to satisfy that area of the artist. The basic recording technology — the way that went was not to do with sonic quality. Not all of it. I mean, some of it was. There have been advances, absolutely, but basic sort of multitrack recording did not go in the pursuit of sonic quality. It went in the pursuit of facilities, bells and whistles.

JB: The difference we have now is so that you don't have to make a decision. So it suits the record label, because they can't make decisions.

Recently we did a recording here that was a new band on a major label. It was alright. The drummer was interested in recording, and maybe not really understanding it, so he's over-fussy, and he was just doing classic mistakes. Like on this section he'd hit the snare there, and then he'd hit it in the middle — and just weird kind of things that he had wanted to do because he had read about but not experienced. That was a bit a battle. But it was alright. We got there in the end, but it took a hell of a lot of processing to make his silly drum kit sound like a normal drum kit, but there you go. Maybe we can develop a relationship and we can get him to use a proper kit eventually. At the end of the day — I spent a whole day with him routining the song, managed to get their structure nice, and we got it pretty good. There was a bit of fighting to begin with but it went well and they were quite excited and realized I wasn't an idiot, and perhaps I had brought something to the song. We did the recording and it was really good — at the end of the day we had a really nice song, and it sounded really good and they were happy. And they were going, "Wow! We've never sounded so good!" They loved it and it was great. Then I double tracked the girl's vocals and it sounded fantastic. I thought the best thing about it was her vocals, and they sounded really good double tracked. I had to make this decision, because they wanted to do some more overdubs. I try not to do any bouncing on the machine, if I can — it's fine, I will do it, but I try not to do it. But if I have to do bouncing, because of recordings becoming more complicated, it will be on things like vocals. Like, if you've got a double tracked vocal, okay that can go down a generation and you can put the double track on, and it's cool. The double-tracked vocals ended up on a single track on the tape machine, and then I did the mix, and everyone loved it. I told her what I was doing and I told the band — "Yeah, yeah. It sounds great!" And then, "Oh uh... the vocals seem to be a bit too effected. Can you do another mix?" I said, "Well, yeah. I can do another mix, but when you say 'affected' do you mean you mean...? I can't change the way the vocals have been recorded. Okay? I can't change that. Okay. I'll do another mix." I did another mix. "Oh, the vocals still sound a bit too effected to me." I said, "Well, because they're double tracked. If she wants to come in we can re-record the vocals..." He didn't understand it. He never returned my calls after that. And how annoying is that? Because I quite liked the group, and it could have developed — but it's a silly thing like that. She could have come in. I would have done it for free and it would have been fine. He's a younger, inexperienced A&R man. He's new and he doesn't mean any harm. I think there's a whole generation — you know what I was saying about musicianship going down, but this communication with inexperienced A&R and manager people — they don't get it. Everyone that they deal with can do something in the push of a button. Mixes can remain exactly the same until the mastering stage. I have to actually make really radical decisions right at the beginning, and sometimes it's really hard work on the level, but I really like it and the band really likes it. Maybe I should have gone back to the A&R guy and got my manager to try and help me, but it reached a point. I listened to the recording again and I thought, "Well, for me the strong point of that recording is the double tracked vocal." So why would I wanna? It's kind of odd. I'm sure other people come up against this all the time, but I literally can't do anything. It's a little bit frustrating sometimes, but I manage to keep busy.

LC: What do you see in the future?

I'll get the new console and an echo chamber. The other thing I'm really thinking of getting, hopefully at about the same time, I'm thinking of getting an [iZ Technologies] RADAR as well.

LC: Really!?

Yeah, yeah. I'm pretty keen to have a different format available. I've heard good things about them. My friend Mark Neil's a big champion with them. He's been doing his last projects on them. They sound really good. I'm definitely interested to find out for myself. It wouldn't harm to have a different format, and it wouldn't harm on certain things to have a little bit more flexibility — even if it's just on the level of people understanding what we're doing, because some people just clearly don't get what we're doing at all.

LC: Do people ever have you track stuff and then take it elsewhere and add more to it?

That's happened, but I don't usually do those sessions myself. I get engineers. I hire the studio out for people to do tracking quite regularly. People come in and just spend a week recording drums, or whatever. Yeah, so that does happen. It's something I'm not that interested in, myself.

LC: I can understand.

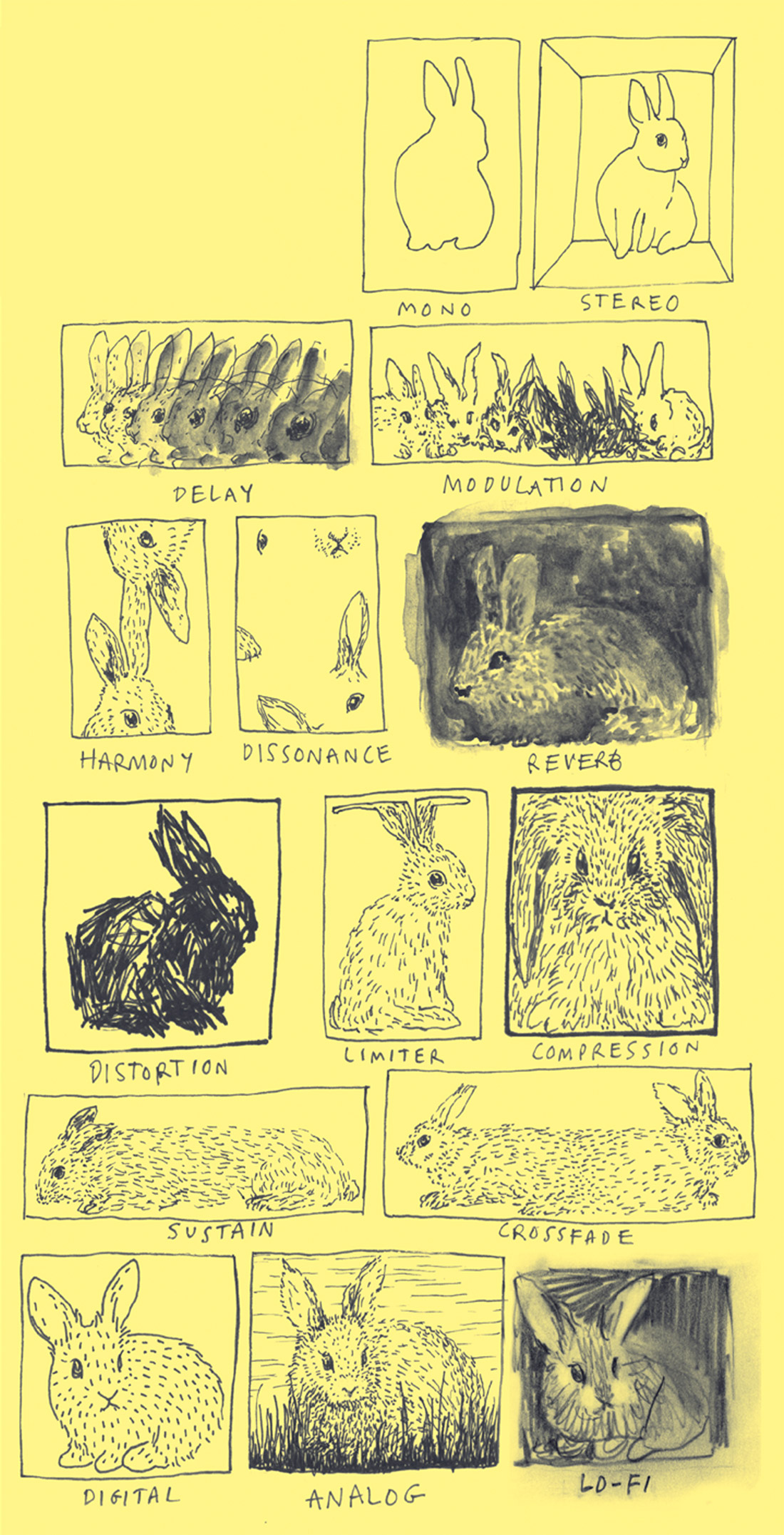

But yeah, I'm quite interested to check out the RADAR. The whole analog and digital debate — I think that's really sidetracked, a lot of it is very ill-informed and a lot of it is debating of things that just aren't relevant. Comparing an analog multitrack with a good digital multitrack with good converters — it's a nice piece of equipment. It's not gonna be that much difference. I really don't think there is. Digital has gotten so much better in the last 10 years. I think the original debate is not relevant anymore. They've overcome all those problems.

LC: It was pretty grainy and harsh early on.

The legend lives on and people that have no experience still may have an opinion on it. I think the only way I'm gonna find out, is to do it myself. The benefits of it are now there to be taken and nearly 90% of the users aren't taking the benefits of it. The benefits being: you don't have to have a high level. The calibration of the tape machine — which can be so confusing and so many different ways of doing it — that's out of the equation. It just plays back what you did and you're not gonna get any noise. But that's not good enough for people! Because then suddenly they've got to have a box that distorts it or "warms" it — it's such a waste of time! If you're tracks are right to begin with, maybe digital is better in some respects.

LC: It's not gonna mutate...

Yeah!

LC: Tape definitely does do something with the sound, with certain different settings, but...

Yes! But, it's not as radical as people make out. It's really not. If you're machine is aligned well, you've got good tape and you've got a good source it's not doing anything that radical. And if you don't cut hot you're not getting tape compression. Some of the weaknesses of it: the tape his thing is always gonna be there. That's not too loud in loud rock music, but sometimes when I'm recording a singing nun I might want it to have no tape hiss. So that's good. So, I'm certainly interested in getting a RADAR.

LC: Yeah. It's gonna be an uproar!

Hopefully. Maybe there will be, because I think the whole analog thing is kind of irrelevant. I really think it is. You don't have to use any of the computer processing involved. I've always thought, "Well, if it's not there, then you don't even have to think about it." And on RADAR it's not really there, so there you go.

LC: Run it more like a tape deck.

I's funny because I was talking about people having an opinion without really having any real experience. Often the people that are most vocal about, "Oh yeah, analog warmth!" and, "Analog this, that, and the other..." They're the people that really need the computer facilities to correct them. Suddenly you're in the deep end and you can't swim. I had a singer/songwriter guy in here quite recently and he pestered me ages ago about doing the record. He wasn't looking for a studio to record in, he was looking to work with me but he was only interested in certain things. To put it bluntly, I didn't like what he was doing. I would have to go into the reasons why, so I think I just priced myself out of the occasion so I didn't have to tell him I didn't like him, because I don't want to upset people. About a year later I get another call from his manager, and I'm saying, "Okay... alright. Let's just do a track." It's flattering that people want to work with you — I respect that. Sometimes someone will approach me, and I really don't like the music, but I need to do it because I'm in a job and we don't live in a perfect world. And then I'm really pleased I did, because sometimes I've ended up really liking it. What I've heard before was something that somebody else did, and when I get a chance to do it I can bring something to it if they let you. So I never dismiss anything anymore. So this guy was a nice guy, and he was full on with, "Oh yeah, we're really into John Martyn and Nick Drake. Those recordings sound great." I said, "Yeah, those recordings sound fantastic. They really do sound brilliant. I'm totally with you." "Yeah. We wanna do something like that!" I said, "Well, I know how those records are made. I've spoken with Geoff [Frost, owner and gear designer of Sound Techniques Studio where Drake recorded] enough times. I've never actually met [engineer] John Wood, but I've played the Nick Drake multitracks and stuff." I said, "Look, I know how those records are made. I know how to do that kind of thing. Obviously you are you, and I am me, and it's not the same, but I can definitely set up a situation for you that will be as close as you're gonna get to that scenario and will have certain sonic qualities about it that you'll recognize as being what you're saying. We can do that, but it's not necessarily gonna be easy." He had just made a really horrendous sounding Pro Tools record with some R&B producer. So I put him in there, and um... they can't fucking do it. I've got really nice condenser mics and everything. Two guys, two guitars, a singer — there's a mic on each guitar and a vocal mic. I'm trying to tell him about dynamics. He's got wild, wild dynamic problems. You can tell that no one's ever given him any training on his vocals. So it's not even registering at -20 [dB], and then it's +6 [dB]. And I'm trying to explain dynamics, "You know what, if you could just bring it here blah blah..." And it only goes so far. "But they blah blah said this, that, and the other..." I said, "Look, you told me what you wanted it, and I'm telling you how we can do it. I'm quite happy to get another microphone out and put a limiter on it. But, you're asking me to do a specific thing, so I'm trying to guide you and show you how we can do that." And we managed to do it a little bit, but they're uncomfortable and they're just not enjoying it, and then they come in and play it back and it's not perfect. Often in this situation and once they hear it in here, sometimes then they're sort of "eyes-open" and they rise to the occasion. Then you get some great stuff. But this one; they didn't rise to the occasion. They were like, "Oh, yeah. I see what you mean." But they were not going to put the fucking work into it. After about six hours the guy just gave up because he wasn't fucking good enough to do it. And no shame at all. No shame whatsoever.

LC: Yeah, but he had been bugging you to come here in the first place.

Isn't that depressing? He obviously had two years of people blowing smoke up his ass. I actually heard them talking one time and I realized, "I know what he wanted. He wanted to come in here, he wanted me to be some eccentric guy that puts old mics out and goes, 'Oh, yeah, that's really warm, hmmm — the sweet spot!' and this sort of rubbish." He wanted all of that.

LC: People fetishize the older records but they don't understand how those were built. Nick Drake and John Martyn records are wonderful. But listen to the players on the Nick Drake stuff. Listen to Nick's playing!

That's it! People are so "fetish" about recording. You're listening to someone singing and playing guitar. Aren't they amazing? I mean the recording's good because it's done by people that know what they're doing. But essentially what you're listening to, what's really amazing, is Nick Drake. And of course Sound Techniques was a fantastic studio. Why wouldn't it sound great? If you can just get the artist and the material outside of the studio and work on it there, then the recording is just a formality in some respects.