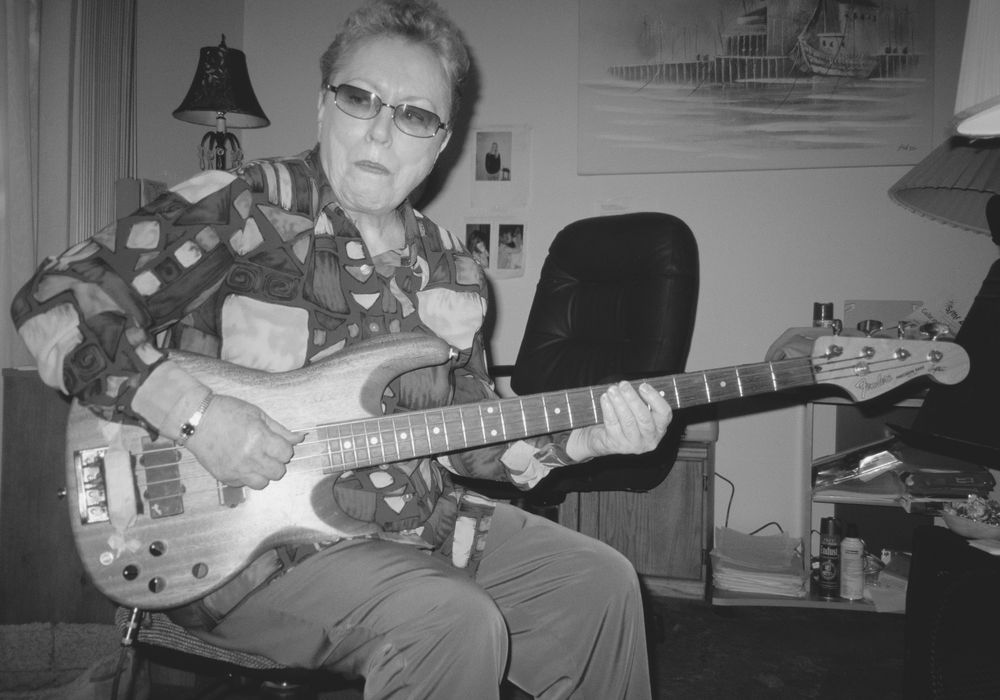

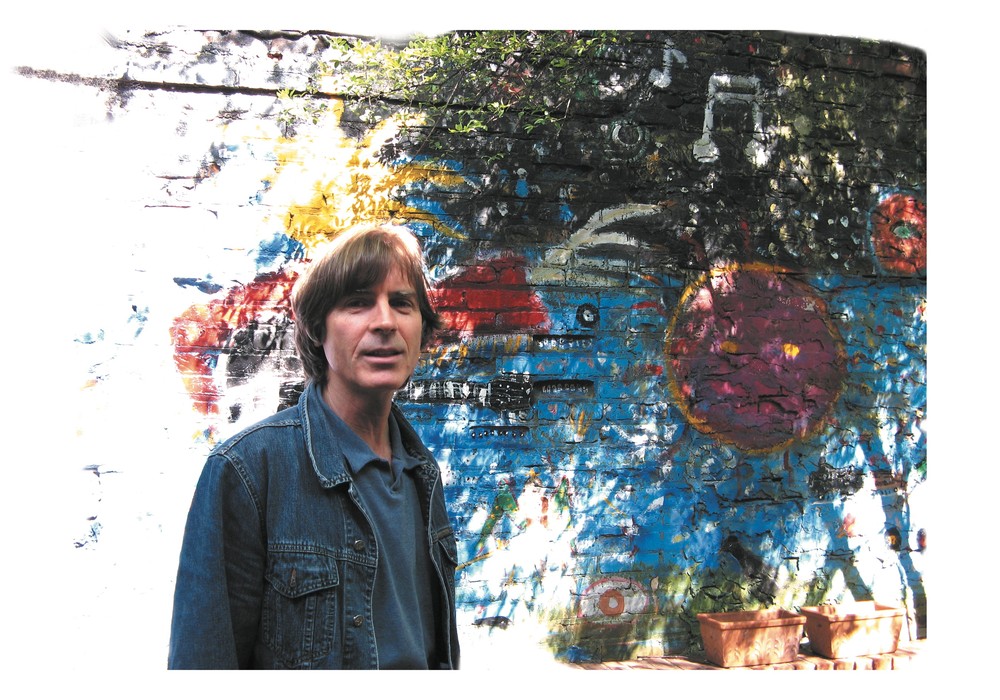

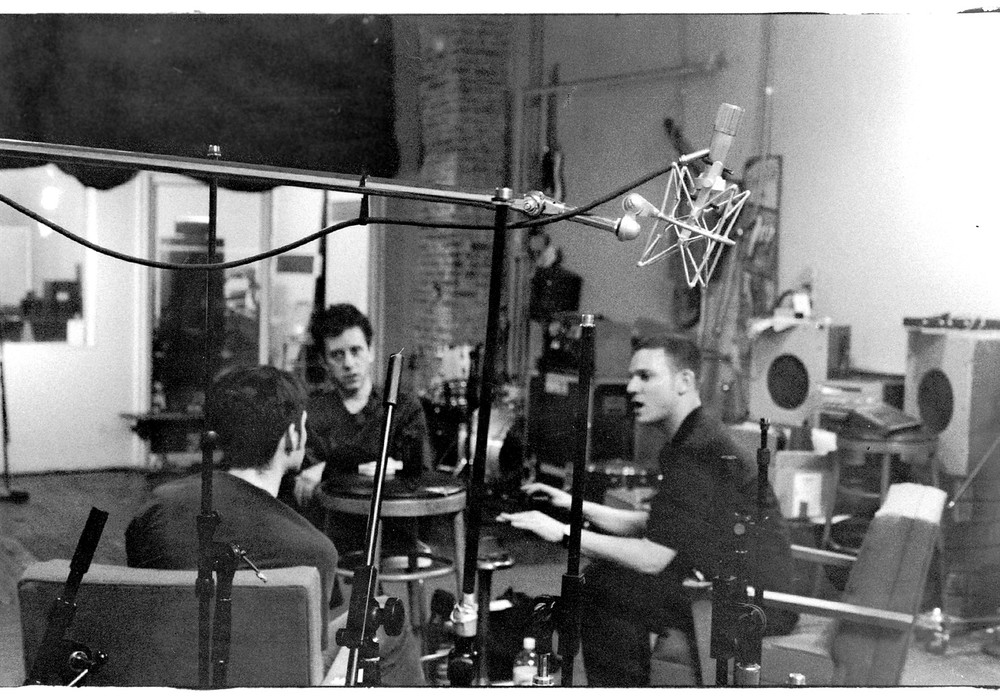

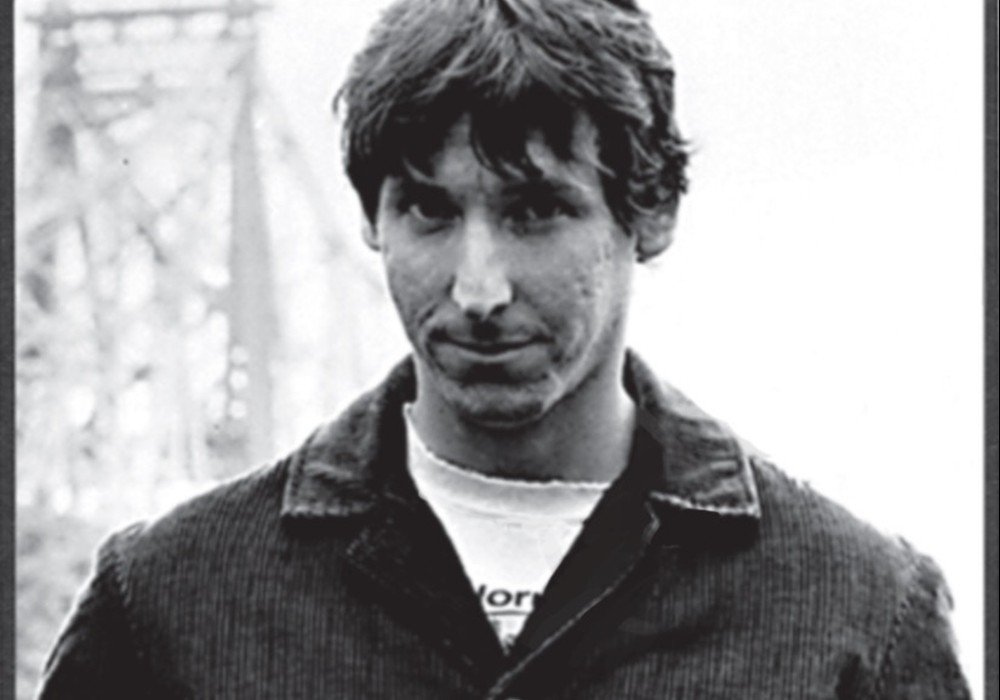

Merrill Garbus is the founder and central figure of tUnE-yArDs, an extraordinary band that I have had the honor of traveling with over the past year in support of their fantastic album w h o k i l l (4AD), which I also recorded and mixed. The album made many year-end lists for 2011, and won the Village Voice's annual Pazz + Jop poll of music critics. Her music, some of which is co-written with bassist Nate Brenner, is fiercely dynamic and unapologetically raw while still showing off a vast number of skills: her unique and arresting voice, her prowess at live percussion looping, and her bad-ass ukulele chops. Her first, self-recorded album, BiRd-BrAiNs, came out on 4AD in 2009 and ever since she's been gaining momentum, in popularity and also as a musician and recordist.

Tell me about the technical process of making BiRd-BrAiNs. You were using a handheld voice recorder that could only record one track at a time, but how did you get it into the Audacity program on your laptop?

The frustrating thing is that I could have overdubbed right into the computer, but I had set up this stubborn limitation for myself that everything must go through a [Sony ICD-ST25 digital] voice recorder! I first might do a drum through it; I'd take a snippet of that, loop it and then I would listen to that, do ukulele next. I would be listening on headphones to what was on the computer, and then press record on the voice recorder, then input it line in, listening to the entire song again as it went into the computer, and then line that up in Audacity. Then I'd start over again for track number three.

You mentioned Audacity doesn't really have a specific looping function, yet you were setting up loops somehow?

It doesn't have a good click track — there's no grid or anything. So I would hear a bar of four, say, and I'd have to do basic word-processing kind of cut and pasting, where you take a section of it and measure it as exactly as you could to create your increment to work with. With that, I would paste for however long that section of the song was. The next time I would do something, if there was more percussion to add on top of that, I would have to be working in that exact same increment. I'd get it down to however many thousandths of a second so that when I cut and pasted, a minute into the song you wouldn't get this weird lag. But as you can probably hear, those lags exist. [laughs]

What was the highest track count on BiRd-BrAiNs?

I think it was maybe around 14. The songs worked best when it was fewer. At a point it would crap out on me and freeze up. After eight, I started getting pretty nervous. I think it was "Little Tiger," that was 14 — that was pretty nerve-wracking.

What was the least amount of tracks — did you have any that were just a single pass on the voice recorder?

"For You," the intro song, I think that was the only one. Even the last song, "Synonynonym," had other sound snippets to it. Some were more complex than others. "Fiya" was way more complex than "Hatari." "Hatari" was three or four drum parts, ukulele and then vocals, versus "Fiya," which had a lot of synth and multiple drum parts that I cut and pasted in different sections.

Did you ever feel like the methodology was counter-creative?

Yeah, especially at the end. I was so close to done and my brain was working faster than the technology was. I knew what I wanted, but what I wanted to do was happening way faster in my brain than it was able to be done by my system.

Did BiRd-BrAiNs turn out the way you originally envisioned it?

Yeah, I think it totally did. I think why I felt disoriented with the second record was because with the first record, I knew exactly what I wanted. Whatever sound I was getting from the recorder felt very right for those songs.

What surprised you, once it was finished?

I was surprised by how far I could push it. I think "Little Tiger" was pretty revolutionary for me, because I could build pretty complex beats using my little system — I could really push it to the max. "Fiya" was another one where I was in disbelief with what I could do with it. But strangely, it was as if the album unfolded before me; I worked hard at it, but it seemed like it was defining itself.

How much does the process of recording an album influence your actual songwriting?

That question leads me to this idea of creating limitations. That's what I enjoy in recording. For w h o k i l l, there were certain limitations that we had. If we hadn't, I would have been overwhelmed by the possibilities. On BiRd-BrAiNs I decided to do everything through this one voice recorder. That was perfect example of the voice recorder defining the sound of the whole thing. Because of the limitation, I stretched that tool to places I wouldn't have, if I hadn't given myself that assignment.

Do you see those limitations influencing the actual core of the songs, or are those tools just useful in allowing you to present the songs the way you want?

A lot of those songs were written before the recording was done. "Jamaican" was a song I was performing live, and I did this recording that sounded totally demented. Then it did influence the performances of that song. I don't think it influenced the songwriting, at least on that album. I would say that for the second album, I had the kind of patchwork and cut-and-paste stuff I had done on the first album in my head as something that was a potential. It's funny, because there's a big difference between what I want to do live as opposed to what I want to do in recordings. I think the songwriting is more based on what I can see myself doing on a stage, versus what I've done in the studio.

Often people rely heavily on the actual technology of the loop whereas, since you're building your loops live, it's always more about a performance. Can you explain the difference between your goals when you set out to make a record versus your goals when you get onstage?

I think it was clearer with the first album, because they were two different animals. With BiRd-BrAiNs I could make this album and it was very separate from the live performance — it was in its own world. I was improvising for myself, versus an audience. I think with w h o k i l l there was a similar vibe as when I perform, and I wanted that. We often wanted more in-your-face sounds, "Let's get it more distorted." I remember when we were listening to "Gangsta," I was like, "Yes!" It had that right attitude and action about it, so I feel like the two came together more than they did with the first album.

You and I have talked about the benefits of coming into a studio and working with me as an engineer for w h o k i l l. Could you tell me some of the drawbacks? Be brutally candid!

I was around other people. That was the main thing. It was actually just that I had a lot of fear going into it — the whole reason I recorded on my own to begin with was that I had had experiences in studios with other people where I didn't feel I got what I wanted. It was such an amazing freedom with tUnE-yArDs to feel like I was getting what I wanted, because I was doing it myself. It wasn't what happened in the end, it was just the fear of that in the beginning that was pretty hard for me. With other albums I'd given so much, and then somewhere along the way — whether it was in the mix or in the raw sounds that we had gotten, or my vocal performance — there was something really wrong that would happen with these other experiences. There are a lot of songs that I just never want to listen to again, and I think that's a tragedy when someone feels that way about their own album. It was hard for me to go back and forth between mixing... you and Nate [Brenner, bassist] were the best people to be in that process with me, so it wasn't a negative thing in the end. But [I had] to grab the tracks and say, "Okay, I'm gonna go mix this now!" I also had to put my foot down and say, "Uh, no you're not. That's not at all what's going to happen." I think now I understand better how that can work. At the time I still had that thing of, "Okay, now I have to mix this all by myself, because that's the only way I'm going to get exactly what I want." I'm really happy with the fact that I could do a lot of the editing myself though.

How important was it for you to be able to take the tracks back and work in your own studio "off the clock?"

I think that might be the crucial difference between those other experiences of being in the studio where those tools were out of my hands. I didn't have any experience with Pro Tools or any program like that, so we got to listen to rough mixes and think about them, but not be hands-on with them. It was crucial to me, not only to have that time that was off the clock, but also because of the way I like to do tUnE-yArDs recordings. It's a lot of experimentation. I could sit there and say, "Hey, could you move this here? No wait. Let's chop it in two and put this half here!" I'd probably drive you crazy [laughs], but spending hours of that on my own trying to juggle stuff around got me to do things that I wouldn't have wanted to "waste time" on in the studio.

The album definitely benefitted from you working on it on your own with the after-the-fact arranging of the recorded parts, and experimenting with the forms of the songs.

Totally. There's also each song of the album and the album as a whole. When a song is shaped, how does it fit into the form of the whole album? I don't know about your experience as an engineer, but for a band to have an idea of what the hell they're doing on an album level...

Well, that's what made you the producer of the record — having the big picture of the entire thing. I was interested in maintaining the integrity of your work in a way that I normally don't feel so conscious of.

I think that we gained people who maybe couldn't deal with the early record. In other words, I think that tUnE-yArDs fans of that album are tUnE-yArDs fans of this album for sure. I think we've only gained people; I don't think we've lost very many. The recording doesn't sound like other stuff — it's not confined to a specific sound. But that's why I think it was so scary. We didn't know what it was going to be, other than, "It's gotta be tUnE-yArDs." It was pretty fun. I'm really psyched for that to happen again someday. Now that I don't have fear about what happens, I feel like it can be much freer.

www.tune-yards.com www.elicrews.com