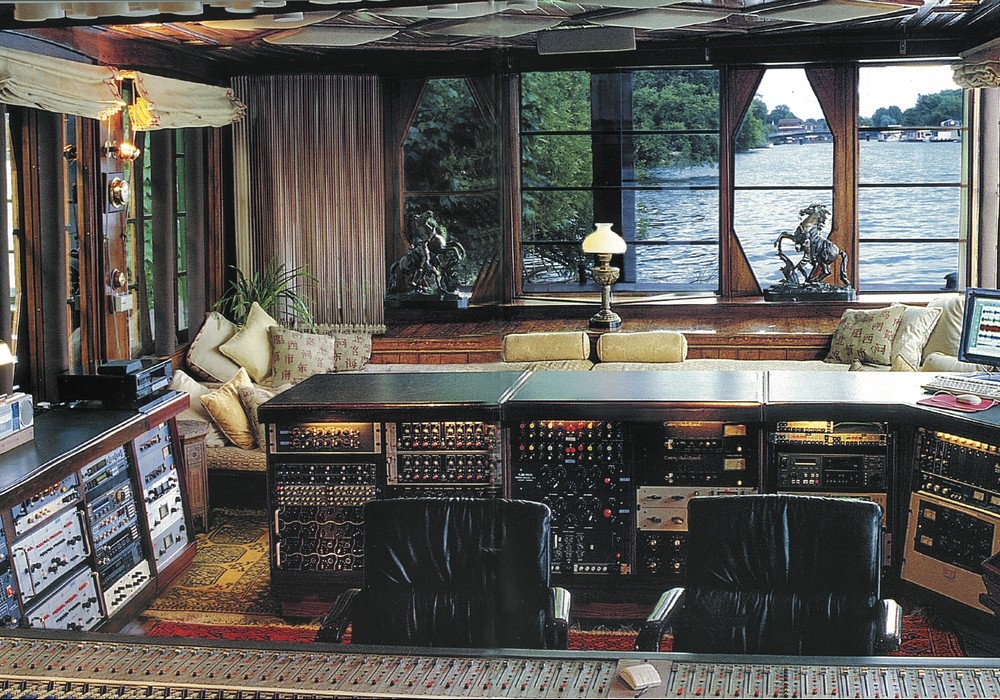

I didn't expect Andrew Schneider's Brooklyn studio to be on a tree-lined residential corner: Unsane records happen here and nobody calls the cops??? But, as it turns out, it's entirely possible to have a studio on a block filled with brownstones and restaurants. Apparently floated floors, friendly neighbors, and New York City's built-in 24-hour white noise generator all help. Andrew got his start in the mid-'90s, playing bass and screaming for Boston noise rockers Slughog. Now based in Park Slope, he spends most of his time making fantastic-sounding loud rock records for bands like Unsane, Keelhaul, Made Out Of Babies, and Cave In. He also plays bass in Brooklyn's PIGS, works as a freelancer for Blue Man Productions (see our interview with Todd Perlmutter) and has a new online label, Coextinction, co-founded with Chris Spencer and Dave Curran (Unsane) and James Paradise (Players Club). Coextinction Recordings has released an EP every month for the past year, each tracked and mixed by Andrew in quick, John Peel Session-inspired, bursts. Andrew and I talked for a few hours in his Translator Audio control room while his dog and honorary co-producer, Brady, napped in the live room.

You started at New Alliance in Boston, right? That's when you were playing in Slughog...

Indeed. I was the asshole in the band who had to bring the 4-track to every practice and make sure that every mic was set up. Then I bought an Otari MX- 5050 8-track. That was my portable rig that I would bring around to all the bands' practice spaces in Boston. Then I started interning at New Alliance — Slughog owed the studio some money. This is actually how I got into it. We were broke. I was like, "Dudes, we're good people but we have no money. What can I do?" I interned for about a year and then started bringing in bands. I got my first official staff engineer job there in 1994. At some point it clicked that I could actually do this as a living. [Eventually] I took over as head engineer — the owner [Andrew Murdock, a.k.a. Mudrock] had made a couple of big records, moved out to L.A., and put me in charge. As head engineer I tried real hard to focus that studio more on the music that I liked. I brought in bands like Old Man Gloom, Converge and Cave In.

Then you moved to New York and opened your own room.

I moved down here in 2003. I tried to be freelance for a while, and I had work from around the country, as well as internationally. But studio prices in NYC versus indie budgets — it didn't line up, even before the collapse of the economy. It made sense for me to have some sort of home base. I set up the first Translator Audio in Williamsburg as a small mix room. I've moved at the end of every lease. [laughs] This is number three — we'll see what happens in three and a half years.

Do you find that your sessions are getting shorter? Cheaper?

Budgets are definitely down. Sessions are a little shorter. I've had to be a little bit savvier on how to make a record and still have something that we're all proud of in the end.

That's a challenge. Even if somebody's trying to talk you down on your rate they still want your best work.

It's not just in terms of the band and budget, but also for me personally — I don't want to put out something that I'm not proud of. I'm an art school kid. I approach records that way. So if budgets are down by maybe a third, what is it in my process that has to change to make sure that I'm still doing work that I'm proud of, and that the bands are proud of?

Can you quantify some of those process changes?

There are ways in which I'll work extra — I'll put in a couple long days or I'll say, "For this mix to work just leave me alone for a day. You don't have to pay for it. I just want to do it so I know I'm set and then we can go." Also you become pretty savvy at scheduling, and understanding what you can realistically do in the amount of time.

So maybe you won't go looking for the perfect clean guitar tone for one little part.

That's right. Something I've been wrestling with a lot — and I'm not 100 percent sure of my own philosophy — but the whole idea of spending three years on a record, and trying to make the perfect record, is ridiculous in today's disposable culture of downloading music and downloading songs instead of full records. People will talk about King of Limbs until the next Radiohead record comes out — there are a few records like that. But, for the most part, from a music lover's point of view, the investment in a record is so much shorter than it used to be. So I've been trying to change my whole thought process. I've been into trying to make things move faster, and not letting people invest too much in the "perfect" anything. Perfect records are boring records anyway.

That's the funny part. Rock records, especially.

With recording strategies these...