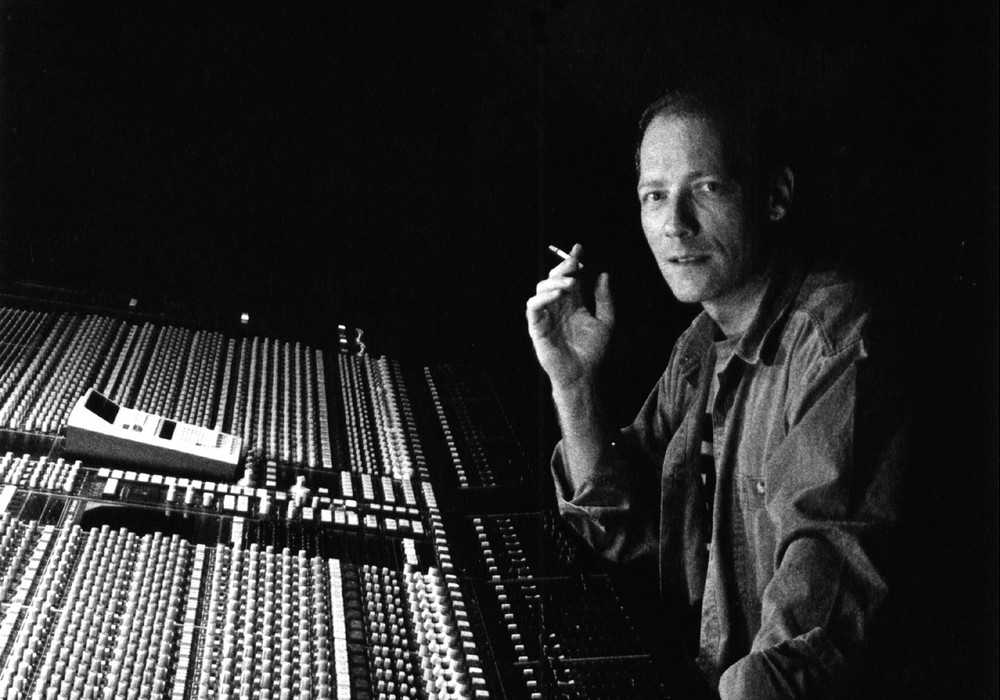

It just seemed like too interesting of an interview to pass up. A new, luxurious studio in Manhattan? An engineer/producer who made her name working with the talented Alicia Keys? I had to meet Ann Mincieli and figure out her game plan, decode her history and see her Jungle City Studios for myself. ("Wow. Look at that view of NYC!") Ann is awesome — a studio denizen who knows the business inside and out. It was great chatting with her and seeing this busy, fantastic place at work.

How did you get your start in studios?

In good old New York, working in the normal studio scene that we all knew and loved. The glory days when we actually locked to tape and did 100-channel recalls. A friend of mine was a session musician in a studio. Back then there was a lot of opportunity in the music industry, and I wanted to be part of it. I realized that when I was 16 years old. It caught my interest in a way where I didn't want to do just one thing — I wanted to learn every aspect. That helps me in today's world. I was an assistant engineer and I was interning at a record label. Back in the day there would be 12 SSL 9000Js installed, all at once, in New York and they needed help teaching people how to use the desk. I did that on my off days. I worked at artists' private studios. I learned every way of working, whether I was locking two [Sony] PCM- 3348s up and flying vocals via the control track and offsets — or using a Lynx and locking three tape machines up — or booting up Digital Performer, back in the day of flying vocals via MIDI notes.

Did you spend a lot of your own time just learning how to use gear?

As an assistant, there was a lot of responsibility; with handling tapes, calibrating 1/2-inch decks, calibrating DAT machines, calibrating converters, locking tape machines and threading tape. There's a whole foundation that today's up and coming people don't know about and have never learned. Like pulling up a mix recall that came from Hit Factory with a 100- input desk and 30 pieces of gear — unity gain from console to console is different. So you really have to develop your skills technically to say, "Hey, I recalled everything but it still doesn't sound right. Let me use my ears. Let me just tweak the [Universal Audio] 1176 differently because..." So, that's the kind of stuff I feel helped me. Always being able to surround myself in these sessions where there were long-term lockouts — from Jon Bon Jovi to Mariah Carey to Hole and Michael Beinhorn [Tape Op #84] to Frank Filipetti to Alicia Keys — I could go on and on. All of these little things I learned along the way helped me become the engineer that I wanted to be.

Obviously watching people like Beinhorn and Filipetti work would be a good schooling.

Yeah, I think Michael Beinhorn is a genius. One time I engineered a session for the Tomb Raider soundtrack — we did two songs with Outkast and him. We were in a digital room locking two [Sony] 3348 [digital tape decks], but at the same time dumping to 16-track, 2- inch. Those days were a lot of fun. I learned a lot from people like that, and from Alicia Keys especially. We grew in this industry together. We built this whole structure 12 years later, in terms of the audio end of things, of how we record and the gear we own. There's an art to recording, and I say this all the time: You hear color and you see sounds. I think people forget that with the digital world today. People are just recording and they're disconnected. Somebody's programming drums in Philadelphia, whom you've never met before, and you're in L.A. You're gonna get vocals from Atlanta and you're going to put the song together like a puzzle. I think Alicia is the best of both worlds. For me, as an engineer, I'm still exposed to the old ways of doing things. We're sort of retro- futuristic. It's painting a picture. I don't know what compressor I'm going to use on a vocal. What does the song call for? Is it a ballad? Is it a pretty song? Is she going for a grimy street sound? What range is she singing in? Is she in the harsh range where I might have to make her vocal a little more round? There're no rules, at the end of the day.

When did you and Alicia Keys first meet?

In 1999, at Quad Studios. She was signed, but her album wasn't out yet. In 2000 she had a studio in a house in Queens.

And you started working there quite a bit...

Yeah, exactly. We moved up through the years.

Has she still got a studio?

She has a Long Island studio.

And now you've put Jungle City together.

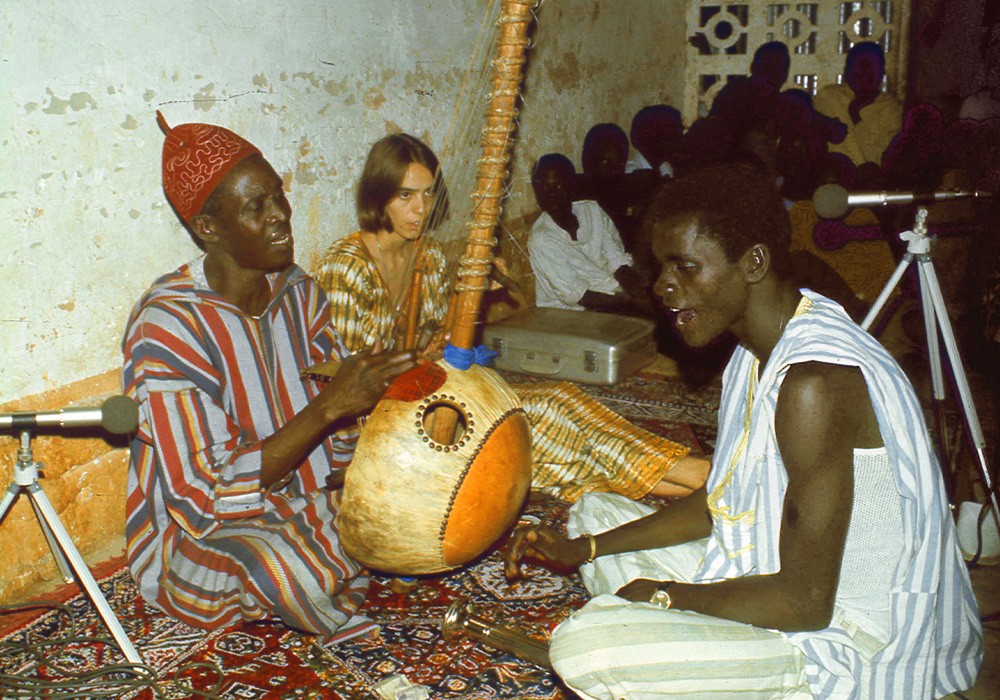

It's exciting. It was a long journey just to find a location. My sister was in real estate and she found this great location, which was important. It was actually my sister's idea — she pulled the investors together. Nobody from the [music] industry is an investor with me. She pulled this together and she did a business plan; and it's been great. I've traveled around the world. I've been in studios in Toulouse, France; Brussels, Belgium; and Milan, Italy. You go to those places and get the vibe and the energy. It's not the latest, greatest gear and speakers, but just to get to see part of what that culture inspires. We tour with Alicia a lot, and on our off days we'll hit some studios. I wanted to have a place like that in New York — for people to have an experience when they come to New York. Have a view, have windows and an incredible space — not just be underground.

Was it difficult to deal with the acoustics of glass?

There are some really cool ways to diffuse sound with glass. Like a lot of our diffusors, people think they're glass but they're acrylic. The speakers are in a freestanding glass wall in order to never lose the view of the live room. There are ways to diffuse and absorb. I had a real big input because, most of the time, the designers aren't the ones that actually use the rooms. I'm a perfectionist, at the end of the day. I learned from building Alicia's studio in Long Island in an old house, sort of like Motown. We gutted it and redid it. When you have a pre-existing structure you're learning a lot about, "Well, if this wall has to come down, we have to put another header up." We even had to change zoning. I've learned a lot about designing. Knowing how sound travels helps the way I engineer — to walk in a room and understand how they treated it. I wanted to do something unique and this is a very unique-looking studio. There are a lot of custom things I thought through. I'm getting a lot of requests to build other places.

To oversee other studios under construction?

Yeah. It's a good thing.

So you're putting in another room now, upstairs?

I'm putting in another room right now, but it's not done yet. There will be four rooms when we're done.

As far as a business model, supposedly this isn't the time to build larger studio complexes.

I'll tell you, I blew that rule right out the window. I've been booked solid since I opened. I think the thing is that artists enjoy coming here. It's a service industry and, if you look around, I'm giving them seven-star service in a seven-star hotel. I supply little things, like slippers and things that you don't get anymore. There's nowhere like this to go to in New York anymore. This is the perfect time. A lot of the older studios are run down and ready to close. There's only one other studio that I work in with my own projects, which is Germano Studios. The budgets are still there and I'm getting all kinds of events. I'm getting video shoots on the roof. I'm getting listening sessions, because of the space itself. We're getting a lot of different types of sessions. It's not just DVDs, it's not just audio and it's not just album projects. I don't turn one thing down. I maximize my schedule. We've had a great year.

That's kind of amazing to say that you've been steadily busy.

I'm getting stuff from Europe, the UK and Japan. I have the New York artists — I work with them all. It's getting people back to New York. I did this because I have a lot of passion for the industry. And this neighborhood is so much fun. The High Line Park is open now and you have views of the water and the Empire State Building. It was really the right time to do it . I had to, I put all the odds in my favor-the location and the gear was important.

I assume you built up a long list of people you already knew and had worked with as well.

Beyonce was one of my first clients; her and Dreams Come True — a pop band from Japan. People still want to work in good studios and there's nowhere left to go. I had a session in from Atlanta for two and a half months — locked-out upstairs. People will come. We made the cover of Vanity Fair and the cover of the New York Times. When I go to L.A. I say, "Where am I going to work? What studio am I going to be at?" I think New York kind of fizzled down for a little bit. This is the heart of where music lives and breathes. The labels are here and the artists are here. The history is here. It's not L.A. — it's here. I wanted to bring something back to New York and build a community up. I think people are coming back.

How many people do you have on staff right now?

It's got to be at least 10 or 12. We can help clients with whatever they need us to help them with, whether it's planning an event, giving them research on a hotel or getting cars. We have a whole underground parking garage.

What else do you see doing in the future?

I have a couple of other ideas that are a little too early to speak on. Obviously I want to do a record label. I always talk about opening up some open mic café, where people just walk in off the street; sort of like the '60s were in New York. But it's too early to really speak on it in depth.

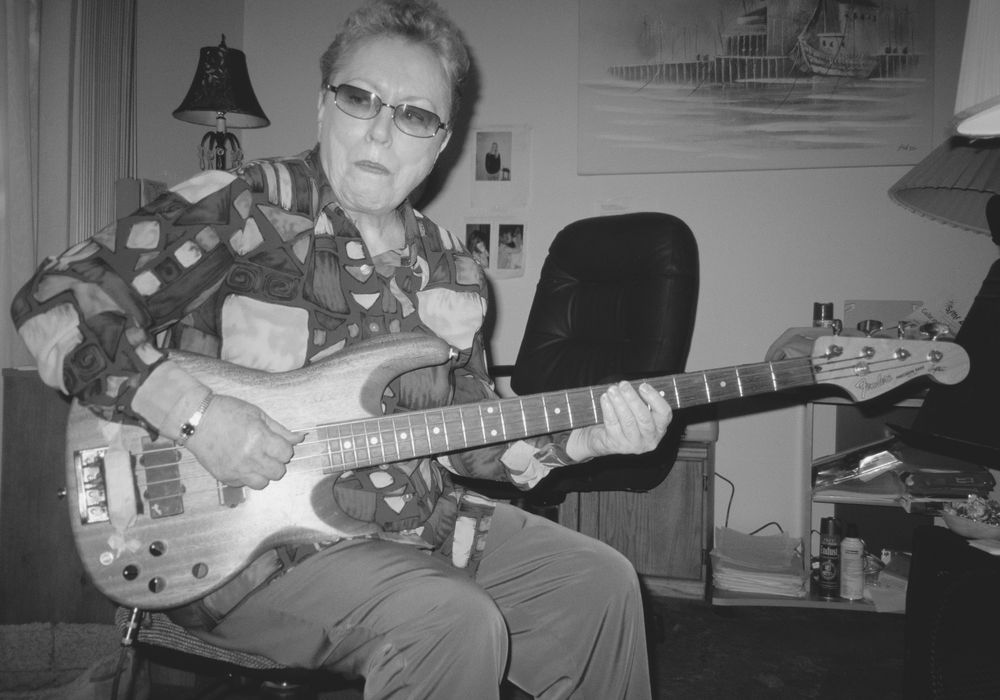

I know you collect a lot of guitars and basses, as well as other equipment. Do you play?

I do. I play guitar and I study with Carlos Alomar [known for his work with David Bowie -ed].

Well, that would help

Being able to study with people like Patricia Carey, Mariah Carey's mom, for vocals and guitar with Carlos — it helps me in the way I engineer. You have to be musical, at the end of the day. You have to relate to how an artist like Alicia is as a musician and understand how she's putting a song together. You need to understand when she says, "Punch me in on the pickup." As much as you have to geek out and learn Pro Tools, you also have to be able to forget about technology. A guitarist will come in and Alicia will show them what she wants. She wants a pretty tone, using a certain chord progression. And these guys are on their barre chords digging in, and it's like, "Why don't you use a four-string strum?" I believe in having the tone in its purest form. Forget about putting nine plug-ins on. Change the tone. Change your pick. It's there where the tone is defined — it's not just at the point where you're pressing "record."

The more you know the more you're able to guide things, if needed.

Every session that I work on, everybody's different and every producer's different. I adjust. It's always adjusting to whomever you're working with — I think that's important.

With this studio to run do you get much time to engineer, mix and produce?

Absolutely. It's how I make a living. I'm in the middle of [working on] Alicia's new project. I'm her engineer and album coordinator. I work alongside her A&R, Peter Edge [RCA Records], scheduling all these producers to come in. I do everything with her. I'm in the album stage itself, doing credits, scheduling studio time, scheduling musicians, researching what musicians to use, as well as buying gear on eBay. That's my real job at the end of the day. That's where I get my salary. Jungle is a side project — you know what I mean? I think being relevant and still working helps you understand what the supply and demand is. What plug-ins do people need? I can say, "We need another expansion chassis in that room because..."

Any parting thoughts about the future of the music biz?

I think the labels have had to really catch up with the technology. They didn't protect the artist back in the day. They could have been iTunes or Napster. The industry's building itself back up and I think you're going to see a lot more artists signed. It's a good time. I try to be optimistic. I can't be in a room with people that are Darth Vaders of the biz. "There's going to be no more music industry." Look at Adele — she's the perfect example. When music is good, people will still buy it.

I can't believe that people wouldn't want music.

Yeah. So the budgets are not as big, but people are still making a living.

Thanks to Eric Agner for transcribing this interview.

_display_horizontal.jpg)