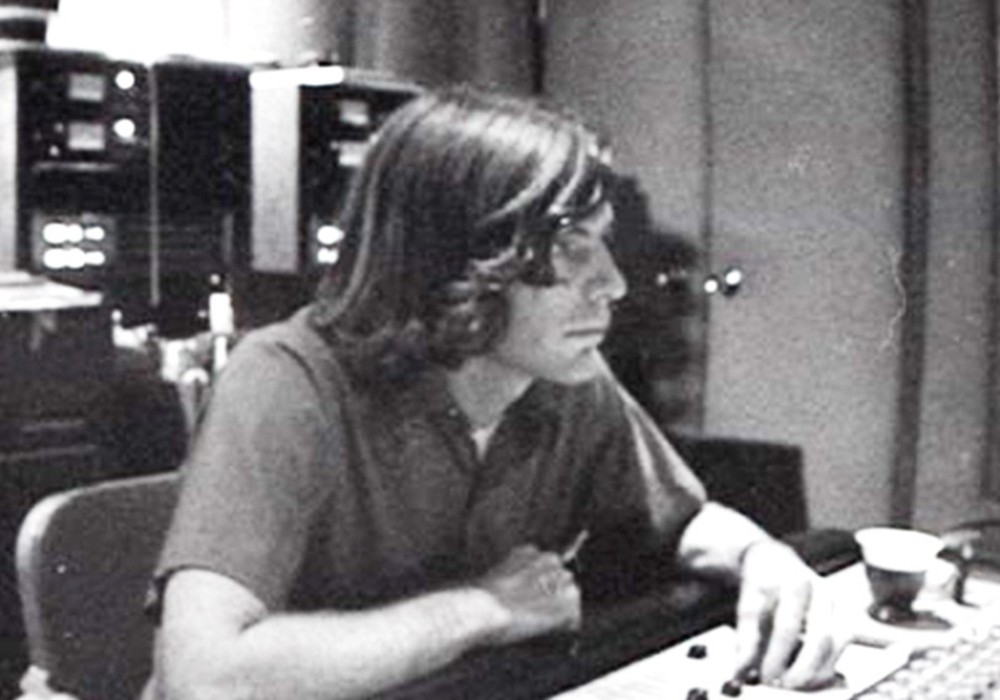

Everyone needs an audio guru. Magazines and the Internet are great, but nothing compares to a veteran who knows you and your work. My guru is Greg Thompson. Greg is an accomplished pro engineer in New York City, and we've been friends since we were kids. When I'm planning a tricky session, wrestling a mix to the ground, or mic shopping, I call Greg for advice and insight. I learn more in ten minutes than I'd learn in ten weeks on a recording forum. When my friend Pierce Backes, of The Yarrows, told me about his audio mentor he told me, "Garris is a wizard with consoles, wiring, mics — you name it. But he doesn't do audio anymore. He worked at big studios in the '90s. He did a few metal records." Which records were those? The answer made my jaw drop. Garris Shipon mixed Corrosion of Conformity's Blind and engineered Brutal Truth's Extreme Conditions Demand Extreme Responses. Whoa. Blind is easily my favorite COC record and Extreme Conditions is my favorite grindcore record of all time. So, okay, those are impressive credits. And then he quit? Garris recently moved to the Bay Area, and we've become friends. I've mostly resisted the urge to badger him with questions about those sessions — or to ask the obvious follow-up question, which is, "Why get out at that point?" Well, I resisted the urge... until now.

What were you doing before you ended up working in studios?

When I was 18, all I wanted to do was get the fuck out of the suburbs, move to New York and make records. I did not go to college. I just moved to New York City. My dad helped me with rent for a couple of months; I got some shitty jobs and shared a tiny apartment. I was a shipping clerk. I shipped fake jewelry. Then I started meeting people. I guess I looked in the back of the Village Voice for people who wanted to start bands. I was fucking insane, and I just wanted to make records. I met the Love Camp 7 guys — who ended up starting Excello [Recording] — in that early time when I didn't know anybody. They recorded a record at Baby Monster, and I went to go hang out with them. That's when I met the guys at Baby Monster. I said, "Can I just hang out here all the time and do whatever you tell me to do?" And they said, "Wait, you can operate a computer, fix amplifiers and you want to do that for free? Yeah, okay!" Baby Monster had two rooms, a Studer room and an MCI room. One day Bryce [Goggin, Tape Op #40] was in a session and smoke started coming out of the MCI. Bryce was like, "Uh, I think this session is over." I ran in, popped the front off, started futzing around and reading the schematics. I found the chip that was burning — it was a regular 741 op amp for the servo. I had one, so I popped it in and the machine started working again. That's the point at which Steve Burgh [Baby Monster owner] started paying me. That was my first real job in recording. I started engineering their night jobs soon after that — TV commercials, jazz trios and little orchestras.

Corrosion of Conformity's Blind came out in 1990. What do you remember about that session?

I had worked at Baby Monster for a couple of years at that point. I studied under a couple of engineers there. One of the guys was Steve McAllister, who was a brilliant engineer. He did a lot of New York Lower East Side bands, these Knitting Factory jazz/art/metal people. He knew a lot of people and he was a really cool guy — really creative and nice. He did all the basics for Blind. COC, those guys are so fucking good. That drummer, Reed [Mullin] — I had never seen a guy like that before. I was a house engineer and I was around when they were recording — he's so precise and so powerful. His drums sounded so good. And the guitar players in that band, their sounds were so good. They sounded amazing without the mics. That's one of the things about that and any other great record that I'd seen made; almost all of them had something to do with incredible musicians. And Steve was incredible at capturing that to tape. I think they'd just gotten the Studer A827, which was a really nice tape machine.

If Steve was the tracking engineer, how did you get involved?

Steve did the basics. And the basics are beautiful sounding. But Steve got pneumonia halfway through the record. Everyone's like, "What are we gonna do?" Steve said, "Uh... Garris can do it!" [laughs]

How old were you?

I was 22. But the thing was, I was always at the studio. And I was good! [laughs] I would do whatever they wanted me to do. They weren't that worried about it. They had incredible confidence. John Custer, the producer, knew it was gonna be fine.

This was his first big record too, right?

I think so. But he was a genius. Everybody on that record was a genius, except for me. [laughs] I just didn't get in the way. That was my goal the whole time.

If you listen to other'90s metal records, but Blind sounds very different. Most records around then sounded more like they were still evolving from the '80s.

Yeah! They're all very hype-y, in comparison....