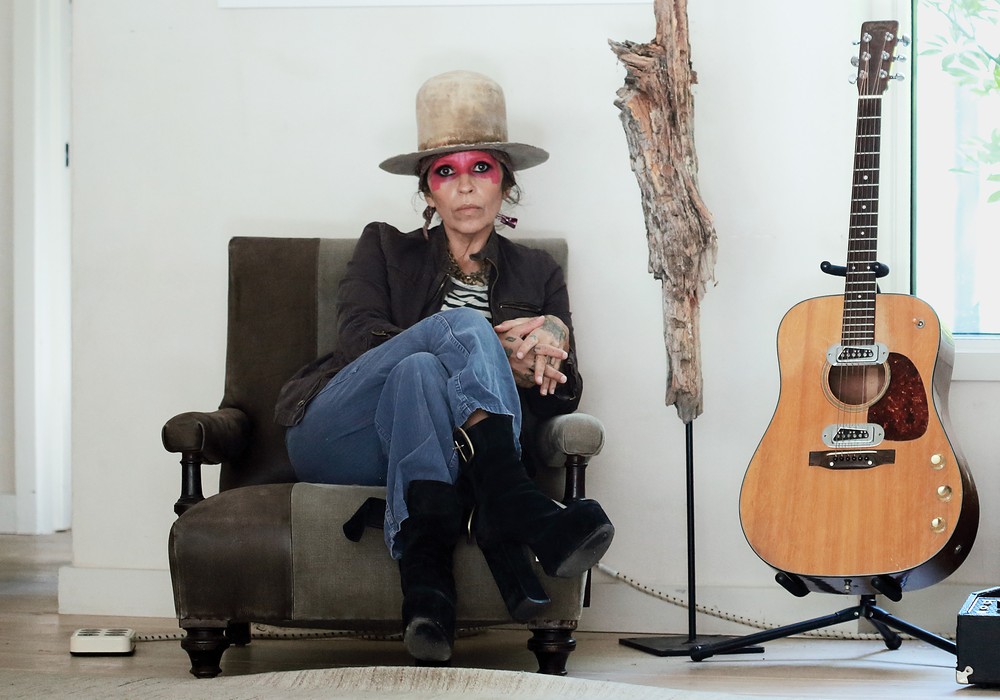

As I sat and listened to Jack Douglas and Jay Messina in Jay's living room, one of the first things I noticed was their friendship. I felt like I was sitting with two brothers — the respect and admiration between these guys was clear. But then I started to see something else. I started to see how they strengthen each other, working side-by-side towards a common goal. These two seamlessly complement one another, encouraging and promoting each other's ideas and creative output. If you weren't paying close attention, I doubt you'd notice any of it taking place — it all happens without pause or fanfare. Obviously, part of it comes from their shared love and passion for their job; thirty-some-odd years of working together doesn't hurt either. But I think the powerful part comes from the trust that exists between them. And, honestly, with such an influential body of work — Aerosmith, John Lennon, Lou Reed, Supertramp, Cheap Trick, Patti Smith Group, and the New York Dolls — you can't really argue with their dynamic. True to their philosophy of keeping their sessions fun, both of these guys are enjoyable to be around — easy going and quick with a laugh.

Was music a part of your lives growing up?

Jack Douglas: Oh, yeah. We're both musicians.

Jay Messina: My father was an upright bass player. He had a trio of vibes, bass and guitar. When I was eight he bought me a little set of orchestra bells. All through high school and for a while after I played in

a band, until I got big into the studio.

Was your thought that you always wanted to be in the music industry?

JM: I knew, mostly from my father. He said, "Get into electronics and keep the music on the side." What I wound up with instead was a perfect marriage of both. I've been really fortunate — I've been playing with music my whole life.

JD: My father worked in a freight yard in the Bronx. Things would always "fall off" the freight trains. My part of the Bronx was really terrible — a lot of gangs, a lot of violence. I liked it; I thought it was okay. So off of a train "fell" a tape recorder and a guitar, and he gave them to me. He knew I liked my grandmother's piano. He thought, "We can't afford a piano, so here's a recorder." I played in bands when

I was very young. I absolutely thought it was where I was going. My parents always instilled in me that you could do whatever you wanted to do. Both my parents gave me a ton of confidence and love.

JM: I've always gone after what I like to do. When people ask me, "What should I do?" I always tell them to pick whatever they like to do the best, what's the most fun, and go after it. I've been listening to, and playing with, music my whole life. I have a friend who asked, "When are you going to retire?" I said, "Why would I do that? This is what I like to do. It's what I would do in my free time."

You two met at Record Plant in NYC?

JD: Jay was the jazz and jingle king over at Record Plant, and I was his assistant engineer. He used to do his dates either early in the morning or all night long. The jingle dates were all really early in the morning. I would write out 40 pieces, set up, and within three hours we'd do a whole airline commercial with a full orchestra, background singers, a lead singer and an announcer. They'd leave with 28 and 58 second commercials.

JM: We'd have about five minutes to get the sound.

So they'd walk in and everything was ready to go?

JD: The chairs and mics were my job.

Jack, were you working there before Jay?

JD: Yeah. I was already at Record Plant. Jay came over from A&R [Recording].

So how long did you assist Jay?

JD: Well, when I was assisting for Jay I was on the cusp of becoming a staff engineer. I had been assisting for most of the engineers there — Roy Cicala, Shelly Yakus (Tape Op #31), Jack Adams — and I was just at that point where I was doing 4-track demos with people. From Jay I really learned how to get it done, make a decision and dedicate the sound to tape. But there was one thing I could never do: when he did an edit, he never marked the tape. He would just grab it at the capstan and lay it on the edit block, because it was the same distance from the playback head to the capstan.

JM: Once you know the distance, then you find the spot on the editing block, so you know to put your thumb there and then just cut. You could do it a lot faster that way.

And you always nailed it?

JD: Always. I was too chicken to do that. Do you ever want to splice a little sliver of tape back into to a tape? No! [laughs] So yeah, we had so much fun. Jay, you had done some rock over at A&R, like Ten Wheel Drive...

JM: The first J. Geils Band...

Jay, where did you get your...

The rest of this article is only available with a Basic or Premium subscription, or by purchasing back issue #90. For an upcoming year's free subscription, and our current issue on PDF...

Or Learn More