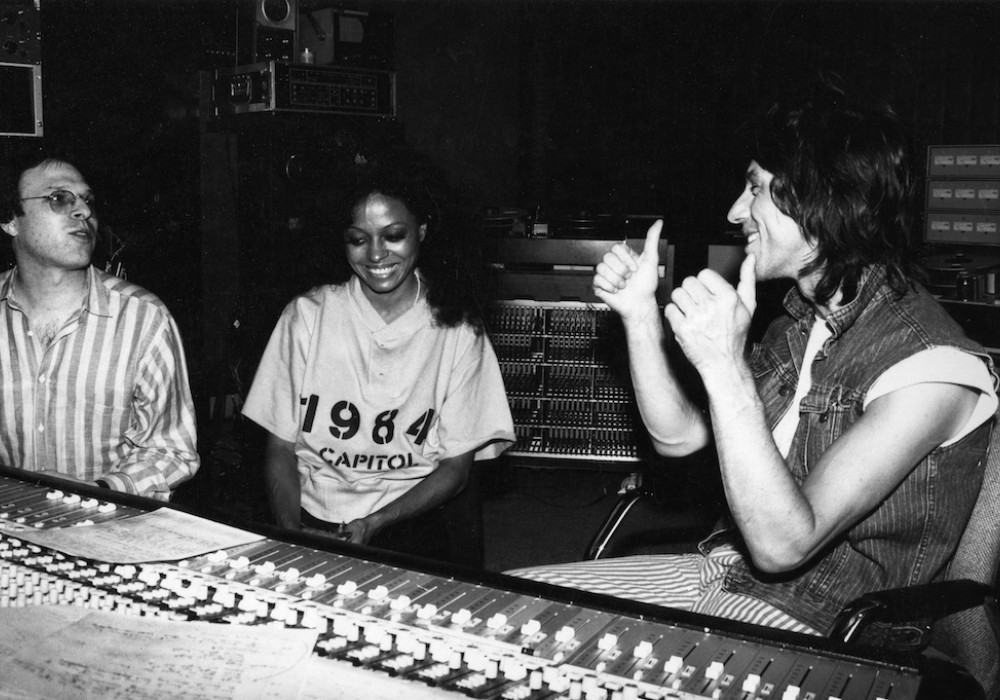

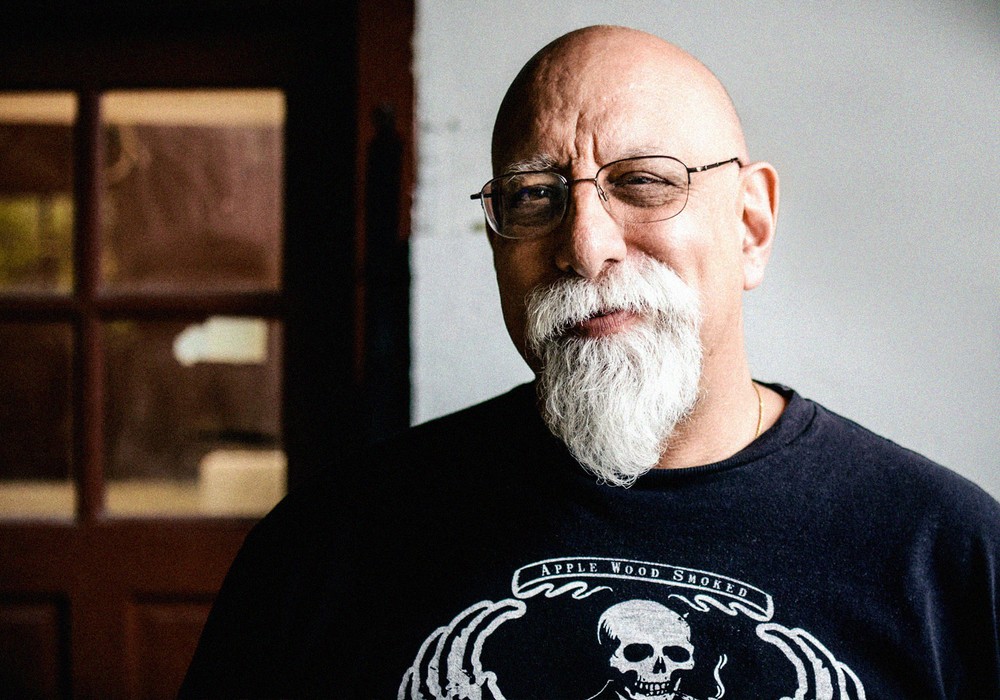

Name an engineer/producer that has Diana Ross, Sisters of Mercy, Devo, Bruce Springsteen, Janis Ian, David Bowie, Bon Jovi, and Steely Dan in their credits. Chances are you didn't think of Larry Alexander. A veteran of The Power Station studio's glory years in the '80s, Larry has seen it all when it comes to making records. Having met through our mutual friend, Steve Masucci, it was only after looking at Larry's credits online that I realized the extent of his studio work, so I had to sit down with him in NYC and learn more about his amazing career.

How did you end up in recording studios?

I used to be a drummer; from fourth grade through college. I was always in bands, and I was the guy who would hook up the PA. I went to college at SUNY [State University of New York] Buffalo I started working in the radio station. They had an awesome radio station — WBFO. They would do live music broadcasts, so they had multiple mics. After a couple of years I became operations manager at the station. Somewhere in college I just decided, "I wanna be a recording engineer." At that point I had never seen a recording studio. I was getting this really early magazine, Recording Engineer/Producer, which was awesome. Between junior and senior years I started applying for jobs. I knew there was a recording studio near my house called 914 [Sound Studios in Blauvelt, New York]. I had driven past it a few times. I went in there and I met Brooks Arthur, and I said, "Hey, how about a summer job?" And he said, "Why should I hire you for the summer, and then in September you're gonna leave?"

Were you studying recording in school?

When I first went to school I was taking engineering. Which has nothing to do with audio engineering.

Real engineering!

Real engineering. I never went to classes. My average the first semester was 0.5 because I never went to classes. I was in the football band, and the orchestra and all that. In that stuff I got As, and in everything else I got whatever the lowest grade would be. I was ready to quit when somebody said, "Why don't you design your own major?" SUNY Buffalo did not have a media department, so I designed my own major in Media Studies. Which meant filmmaking, photography, electronic music — everything I loved. From that point on I had straight As. During my senior year I started sending out resumes to all the New York studios, and everybody said, "No thanks." I called A&R Studios and I said, "I know you said I can't get a job there, but can I at least see the studio? I know I want to be a recording engineer. How about a tour?"

The first studio you saw was A&R?

Except for 914 that I'd stopped in. A&R- they said, "Yeah, sure." I went down there, and who's standing there but Brooks Arthur. At that time, I had no idea that 914 was a satellite studio of A&R. Brooks and two people from A&R had gotten together and started 914. I didn't know that. Brooks asked me, "What are you doin' here?" I said, "I'm looking for a job!" He said, "I just fired my assistant yesterday." I went in, we spoke for a while, and he said, "Look, I'll try you out. You gotta work for no pay for a couple of months." I said, "Fine! Just let me in!" He said, "I can't start you right away, because we're right in the middle of an album. I don't want to bring you into the middle." I said, "Really, who is it?" "James Taylor." I'm like, "You gotta let me start! I'm a huge James Taylor fan!" He said, "No." So, James Taylor and Peter Asher were there. A couple of weeks later he said, "Alright. You can start on Monday. We've got a new guy coming in for his first album: Bruce Springsteen."

Had you heard the name at all?

Nobody had! He was nobody. I was assistant engineer on Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J., The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle, and then half of the Born to Run album. In the middle of that album Bruce couldn't stand his manager, Mike Appel, anymore, and he couldn't stand his contract.

When we interviewed Louis Lahav [Tape Op #56] he talked about this.

Yeah. I was an assistant to Louis Lahav. Bruce found manager John Landau. He said, "We're going to the Record Plant." So they went down to the Record Plant and started the album over. Somewhere along the line, Bruce said, "Let me hear that original version of 'Born to Run'." They listened to it, and it blew away the new version. So that one song ended up on the final album. That one song was recorded at 914 studios.

That's funny.

I worked with Brooks for three years at 914, and then someone else bought the studio. I was an assistant. Janis Ian's Between the Lines was the first album I actually engineered — I won a Grammy award for Best Engineered Recording, non-classical.

"At Seventeen" was a huge hit.

Janis Ian was nominated for tons of Grammys that year. She won another Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Performance — Female.

You played some percussion on that album, too.

I might have played tambourine or something. Those were the days. You know. 16-track, 2-inch was state of the art. I learned a lot working with Brooks.

Brooks went on to do a lot more stuff in L.A.?

After those three years Brooks moved to L.A. I still work with Brooks every once in awhile — whenever he comes to New York.

You ended up working right near where you grew up.

Brooks was drawing some major acts. We had Melanie — she was really big at the time — and Blood, Sweat & Tears recording in there. I was just in the right place at the right time.

How did you get from 914 to The Power Station?

A guy named Morty Jay bought 914 and hired me as chief engineer. He took my Grammy and stuck it on the wall with a spotlight on it. [laughing] Morty eventually moved away. Something happened and he moved to Florida, and he basically gave me the studio.

That's crazy.

He left in a hurry. I ended up with this studio. At that time 24-track had come in and everybody wanted to record 24-track. We didn't have the money to buy a 24-track. We had a 16-track, and everybody thought, "Well I'm not gonna record 16-track. I'm gonna record 24-track." Morty bought the studio from A&R, but the equipment wasn't paid for yet, so we had that loan to pay off and there was rent, electric, phone, tape... there were a lot of bills. When Morty took it over, it was called Ultima Studios, and then when I took it over I changed the name to Creation Station.

So, you survived a while?

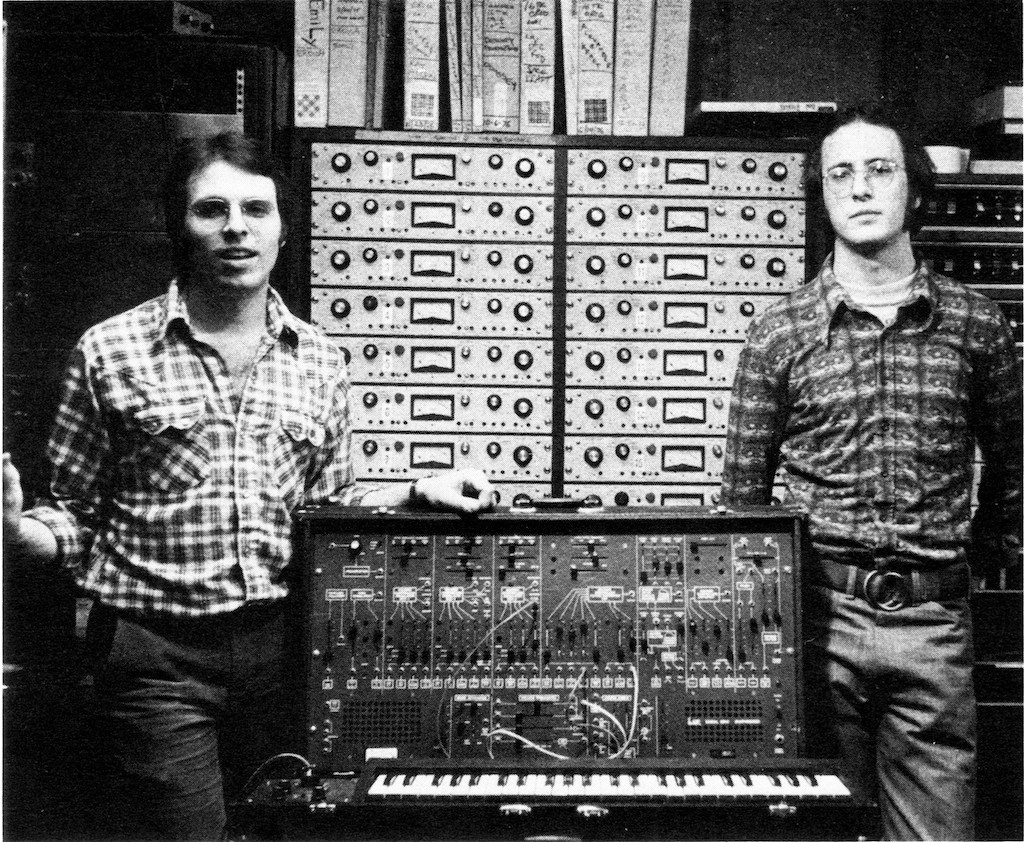

About six months. Finally a guy from A&R wanted his gear. We'd missed a lot of payments. We weren't paying the rent. The only thing we were paying was electricity. He finally said, "Look. You're done. Don't book anything after Thursday." On Thursday a big truck came and they took all the equipment. 914 closed. I'm thinking, "Alright. What am I gonna do now." At the time I was also doing some synthesizer work. My friend Jack Kraft, who's a great keyboard player, and I were listening to Walter Carlos, and we were saying, "Man, maybe we can do something like that!" We were like, "We're not gonna do Bach, because that's been done." And Jack said, "I have this pocket score for the Nutcracker suite." I had an ARP Synthesizer. We took the ARP into 914, and we laid down four or five tracks. We were trying to see how much we could recreate the sound of a real orchestra. A client I was working with, who worked for ABKCO Records, heard some of the stuff we were doing, and said, "I'm gonna get you guys a record deal!" He actually did get us a record deal with London Records to do a Tchaikovsky album, so we did the full Nutcracker suite, and the 1812 Overture — all on synthesizer.

What was the name of this project?

Kraft & Alexander. So I had this synth programming background. A friend of mine, a keyboard player, was doing a session at The Power Station. He said, "Larry, bring your ARP down and program it for me. I gotta play this part." So, I went to The Power Station's Studio B. I don't remember what the project was, but I'm programming on some song and I'm thinking, "Wow, this studio sounds pretty good." Bob Clearmountain [Tape Op #84] was the engineer. I said, "Bob, who do I talk to about getting a job here?" He said, "They don't really hire engineers. They train their own engineers." I said, "Really? Who's the manager of the studio?" So, I met [studio manager] Bob Walters, and he said, "You're over-qualified. We would want to train you our way of engineering." I'm like, "Alright. Train me." He said, "You'll have to start as an assistant engineer." I said, "Whatever you want."

Was he thinking he was gonna have to pay you too much?

I think they liked to bring up their own engineers. They liked to discover young talent. I went there and started working as an assistant. I was an assistant for two weeks, which was good because I learned where the mics and everything was. Then one day some engineer didn't show up for a session and they were like, "What are we gonna do! We got that guy, Larry. He said he's an engineer." So I did the session and that was it. I never assisted after that. The client said, "I like this guy, Larry! I wanna work with him!" So there I am working at Power Station at that time the studio had six engineers. They had two studios, and they were working 24 hours a day. Then I met Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards [Chic], who were big then. The thing about Power Station was that some projects, like Chic for example, everybody would work on because they wanted to work all the time, they were one of the original big clients at the Power Station. They'd go, "Oh, Clearmountain is unavailable? Give me Larry." They didn't care! We were all good. There wasn't such a big thing about freelance engineers back then. People would come to The Power Station because they thought The Power Station gets really good sounds.

Right. You didn't have to bring someone to get the sound.

It was Bob Clearmountain, Neil Dorfsman, James Farber, Scott Litt, Bill Scheniman, and me.

And Tony Bongiovi.

Tony was one of the owners. He engineered his own projects.

Were you and Clearmountain and the guys at Power Station exchanging ideas and talking all the time?

Oh yeah. We would always stop in on each other's sessions. Bob is such a genius. I think Bob invented gated reverb as far as I know. He'd have these EMT plates going through Drawmer noise gates, and triggered by the snare drum. He'd be feeding dry tracks out into the live room and re-mic'ing them. He was really an innovator and was really willing to share. We were all friends hanging out. He'd be on a project, and if he couldn't make one day he would say, "Come on in and mix it."

It's a very good breeding ground there.

That's what doesn't exist today! Since everyone has their own home studios now, people learn by themselves. So, at Power Station they were assigning me these sessions. Like, "Larry. You've got the Stones tomorrow. Oh yeah, you've got a Bowie album coming up next month..."

Is that when you did Scary Monsters with Tony Visconti [Tape Op #29]?

Yeah. The credits are a little funny on that album. Tony came in as producer, I engineered the sessions, and then Tony took it to his studio in England [Good Earth Studios] and did some over-dubs and mixed it there. The album comes out and it's all written in Bowie's handwriting — like he wrote the credits. It doesn't say, "Produced by" anywhere on the album. It says, "Engineer: Tony Visconti. Assistant Engineer: Larry Alexander." But I had an assistant engineer! Jeff Hendrickson. I forgot what credit he got. I saw Tony after that, and he said, "I'm really sorry about that." Credits are weird. They're not always right. That's one of them that was not right. Another one were the Springsteen albums I worked on as assistant engineer. Never got any credit. They actually went out of their way to promise me credit, because at the time Bruce was just starting. I had this beautiful Martin acoustic guitar. They made me drive home and get my guitar so Bruce could borrow it to play on Greetings from Asbury Park. That whole album is my acoustic guitar. They said, "Oh man, you're gonna get credit for this!"

I think we all experience that at some degree.

I've had the opposite happen.

Was it a good credit?

Yeah! Steely Dan. I did one session with Steely Dan. The album [Everything Must Go] comes out and it says, "Engineers" And it lists all the engineers, and my name is right in there with Elliot Scheiner, and I went, "...Okay!" The session I did was kind of interesting. At the time I had a manager, Jill Dell'Abate, and I had been using Pro Tools since '96. I was lugging my equipment around to all the studios in New York. Then one by one people started getting their own Pro Tools rigs, so I got less and less calls for that. Right around the time I was saying, "I haven't carted my rig for a couple of months. I'm gonna take it out of these flight cases." Then the phone rings and Jill says, "Larry, are you a Pro Tools tuner." I said, "A Pro Tools tuner? I don't think so... I don't even know what that is." She said, "Oh. Steely Dan needs a Pro Tools tuner." I said, "I am the best Pro Tools tuner!" I forget what studio they were at. I brought my rig over, and they said, "We have a synth solo on this song, and we need it to be tuned. It's a little out." They have ears like nobody else. So I said, "Yeah! Sure! We can do that!" They were recording on Sony digital 48-track. They said, "Take this synth track, put it in Pro Tools, and we're gonna tune it. We want you to make it a tenth of a cent sharper." I raised it a thousandth of a halftone and I play the song. The solo comes. They're listening to it. "Let's try two tenths." They listen to it. "No. Definitely one tenth." "Okay! Anything else?" "We have this vocal we want you to tune." I put the vocal in Pro Tools and I think I'm gonna get my hands dirty, ya know. I'm doing some really cool graphic tuning. They say, "Do you have Auto-Tune? Put Auto-Tune on there." I put it on. They go, "Great! Thanks man! We'll call ya!" And that was it.

That was a day's work?

They never called me after that and I got credit on their album as one of the engineers.

You worked on the early Bon Jovi records.

Jon Bon Jovi is Tony Bongiovi's second cousin or something. Jon was always hanging around the studio. He had a band. Tony said, "You wanna record? I'll get one of my assistant engineers, and we'll record your band." So they started recording their band, and basically they recorded their first album as demos. They had a song called "Runaway," which they entered into a battle of the bands for WPLJ radio. They won the contest, and the prize was a recording contract with Motown Records. So WPLJ started playing the song a lot, and Polygram heard it and said, "We want that group." So they bought the contract from Motown. So he ended up on Polygram. Meanwhile, Jon was playing the master for somebody, and he accidentally destroyed it.

Like the master on the multitrack, or the mix?

The mix. Of his hit song. It got stretched or something; I can't remember.

That's something that wouldn't really happen these days, is it?

It had to be re-mixed. I think Scott Litt had mixed the song, but he wasn't available. So I came in and mixed the song. "We want you to mix everything!" So I ended up mixing the first Bon Jovi album [Bon Jovi]. When they went to do the second album [7800° Fahrenheit], I ended up recording that album, but didn't mix it. I can't remember why. I think they were starting to have a falling out with Tony at that point. So the third album [Slippery When Wet], we had nothing to do with, and it went mega.

What record did you do with Devo?

I did an album called New Traditionalists. This is right after "Whip It," which was their biggest hit. They came into The Power Station. They'd heard of me and they asked me if I wanted to record their album. They played me a demo of this new album that they were gonna do, and I said, "That sounds finished! What do you want me to do?" They were crazy, really early sampling guys.

They didn't keep the demos?

No. What's funny is between recording the demos and these sessions they'd bought all new equipment. They had double Minimoogs built They actually bought a tuner for the first time. We met in the studio and they're going for a bass sound. Maybe two or three oscillators, and they would tune each oscillator — it was one of those strobe tuners — and they would tune it until the oscillator did not move for at least a minute. So they got every oscillator perfectly in tune, and then they would put it all together and the sound was horrible, because apart of a fat bass sound is that phasing. They'd be playing and every 30 seconds the bass would just disappear.

Just phase out?

Yeah. It would cancel itself out, and then 30 second later it would come back. They said, "What's going on here man? I think there's something wrong with this studio!" We're trying different control rooms and everything; until we finally figured out, "Hey, turn off the tuner. Let's try doing bass the old way." Then it started working again.

That's a lesson to learn.

So, they were great. They were great.

So, did you end up working on the whole record?

Yes. We recorded it in New York, and then we mixed it in Los Angeles at The Record Plant.

You worked on Sisters Of Mercy's Floodland.

That I actually co-produced.

That's one of their most famous records.

I was working with Jim Steinman on various projects; Bonnie Tyler...

Did you work on her song "Total Eclipse of the Heart"?

No. It was after that. Andrew Eldritch, from Sisters Of Mercy, was a big fan of Jim Steinman. He hired Jim to produce two songs, and I was working with Jim at the time, so I ended up engineering. So, Jim produced those two songs: "Dominion/Mother Russia" and "This Corrosion." Andrew had been producing himself over in Manchester, and he wasn't getting anything done — he basically had a mountain of tapes. They didn't even know what was on the tapes at that point. So, his management asked me if I would go over there, and help sort things out.

How many reels was this?

At least a hundred reels. I went over to Manchester. They had safeties, but they didn't know which were the originals and which were copies. They didn't have the track sheets... it was just a big mess. So, we spent a lot of time going through the tapes and trying to sort them out. The first thing I did is I'd lined up all the tapes and numbered them. So, then every tape was unique. Then we continued, and eventually did the album.

Were you building the album out of that stuff you were finding on these tapes?

I don't think we used all that much of what was already there. I think we pretty much started over.

Was it good to go through and find the ideas?

Yeah. Yeah, we might just use one loop from a song and build everything on top of that. Andrew was really creative. I guess the deal was that there had been a band, Sisters Of Mercy, and they broke up. Andrew said, "I'm gonna keep the name." And the rest of them said, "No, we're keeping it."

The guys that became The Mission?

Yeah. They said, "We're keeping the name. We're Sisters Of Mercy." Andrew rushed into the studio, and recorded an album and put it out as Sisters Of Mercy. He's like, "I'm Sisters Of Mercy!" Basically, he did everything. There was a bass player, Patricia Morrison, but he wouldn't let her do anything. Even on the album you see his face and Patricia's face is off in the clouds kind of fading away.

How long did that album take?

It took a while. Manchester is kind of an industrial place, and we were in a studio [Strawberry Studios] that had actually closed. So we got a really good deal. They said, "If you wanna work in here, you can, but we have nothing to do with it." We recorded in Manchester, and then we were supposed to mix in Bath but we weren't done recording. Bath is the opposite of Manchester. Bath is like sunlight, really bright, beautiful, and we worked in this place called The Wool Hall. It was actually an old sheep farm. Any building that they built had to be in the style of what was already there, and it was beautiful, brand new, and really nice. We finished recording, and then we ended up mixing in Air Studios in London.

That must have been a treat.

It was amazing. They had one of the first SSL consoles.

Was that a little hard getting used to?

No, it wasn't that different. It was an SSL. Some of the routing was a little different. So, Yeah that was really good.

You jumped into Pro Tools rather early.

I love computers and that kind of thing. When I first bought Pro Tools, it was 16-track. I think it was Pro Tools 3. I remember the reason I got into Pro Tools: Someone had done a video of interview of Diana Ross, and she wanted to create a bed of her music under the interview. We would do it on 24-track tape. I'd done this with her a couple times. We would take the first song and put it on two tracks, and then another pair of tracks for the second song, then we'd go back to the first pair of tracks and just overlap them. Sometimes, when we were a ways into it, she would say, "Oh, I want to change the third song." This would screw everything up, and you'd pretty much have to start over. We had time booked at Unique Studios. They came out and said, "The board just went down. I don't know what we're gonna do." They said, "Well, the only other studio we have is this Pro Tools studio." I said, "Okay, we could do that." I knew nothing about Pro Tools. I said, "Does anybody here know how to run that thing?" "Yeah. This guy knows how to run it." So, we go in there and I'm looking at this guy running Pro Tools, and about a half an hour into the session I said, "Let me try that!" Because I could see exactly what he was doing. Just the fact that you could slip and slide the tracks... it was just like, "I gotta get a Pro Tools rig!" It was perfect. Not that long after that I was working on music for a film project, and we had to rent a Pro Tools rig for a couple of months. I said, "I'm buying a Pro Tools rig. Rent mine." I bought a Pro Tools rig and they rented it for a couple of months, I watched a guy running it, and that's how I learned a lot about it. I wasn't even the Pro Tools operator; I was the mixer. Then after I learned how to operate it I started renting it out to people. I put it in flight cases and I would hire a cartage company that would lug this stuff around for me. People were just amazed what kind of editing they could do. For a number of years I was lugging that stuff around New York.

It paid for itself.

Yup. I got my first rig in '96. Around '96 it was almost starting to become usable to record music on. And it just got better and better.

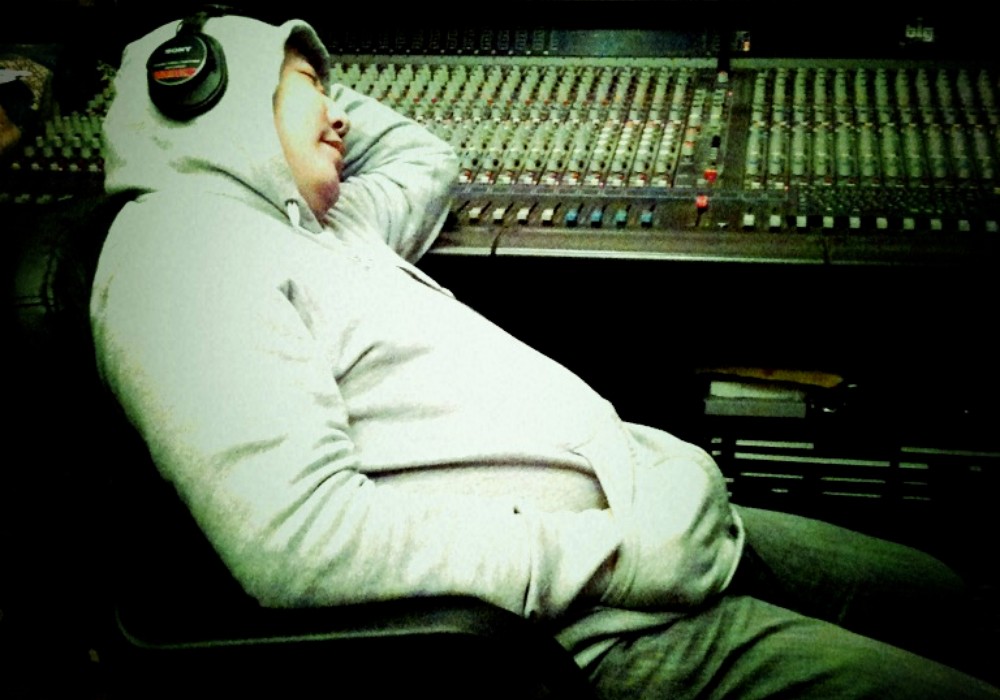

So what kind of studio do you have at your place?

I have Pro Tools. Not a huge mic collection. I have lots of friends who lend me mics when I need mics. It's basically in my basement, but it's a pretty decent sized room. I've had ten people in there. It's not a small room, but if you put ten people in there it's a small room. My neighbors aren't right on top of me, so it's okay. I live in a quiet neighborhood. I never did any sound proofing or anything. If we're doing something really quiet I just ask my wife not to stomp around for the next hour or so.

Do you do mixing projects there?

I do all kinds of stuff. I do bands, I've done a couple of films. I did a film last year — I know the composer, but I didn't see him once for the whole thing. He would email me files, I would mix them, send back the mixes, he would make comments, and I would remix. All online transfers.

You don't have to commute for that.

I've been doing almost all my work down there. It's working out great. I love it. That space is one of the reasons I'm still working. People from my past find me via my website and they want to record.

I assume you feel like mixing is something you've got a good handle on.

Mixing is one of the harder things to do. A lot of people can track guitars, a piano, or a set of drums, but getting a mix to really work is probably one of the most difficult things to do. I think I have an affinity for that.

What do you feel you bring to a session?

I really love music. I think it's partly making people feel comfortable. I'd never say, "No, we can't do that." I'm willing to just go with the project. I give people what they need, and there's gotta be a little talent in there somewhere. I've been around music my whole life. I've been doing this a long time, and I would say that more than 90% of my projects have been really great. Yery few bummer projects.

What do you think leads to a bummer project?

Bad music and bad musicians! And then there's talent. A lot of people have it. But some people just don't.