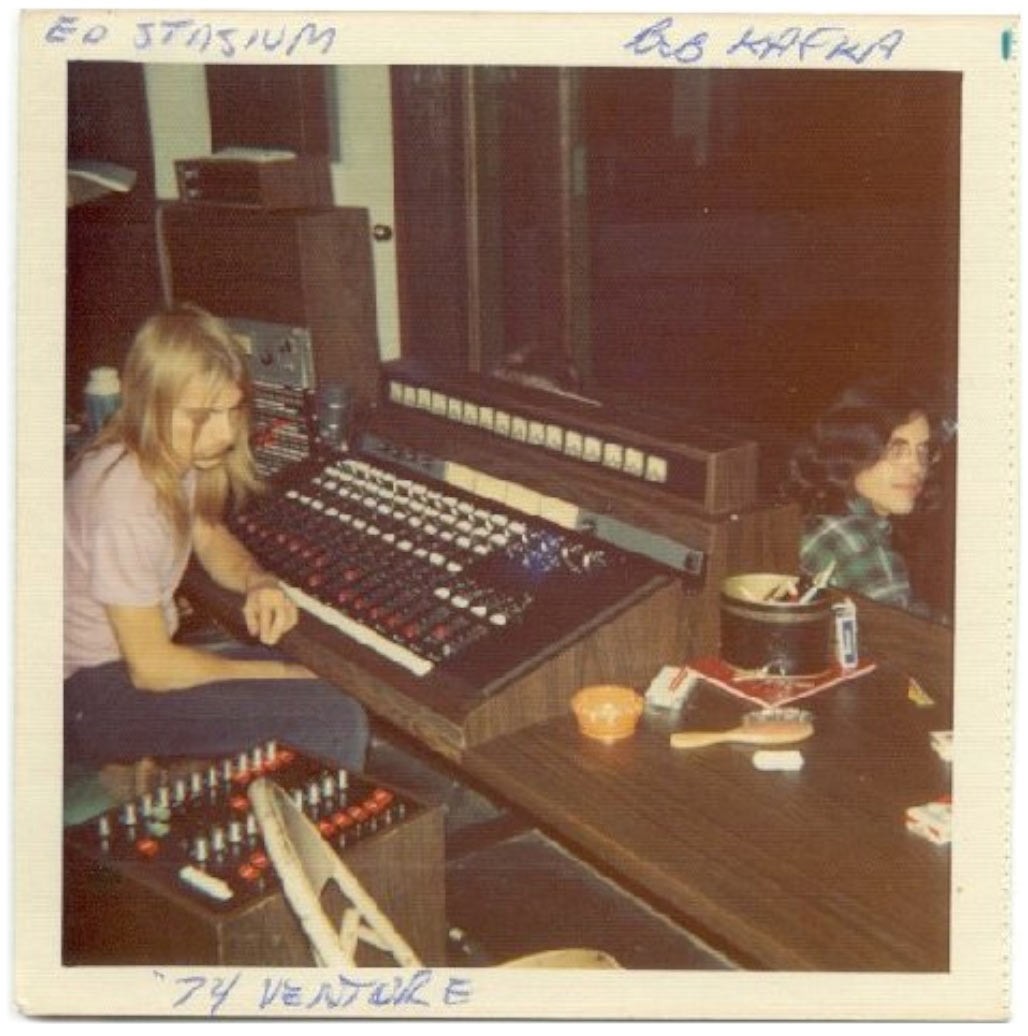

I'd seen Ed Stasium's name on records for years; The Ramones, Talking Heads, Mick Jagger, Peter Wolf, Living Colour, Soul Asylum, and The Smithereens to name a few. But little did I know that Ed's engineering chops stretched back to songs like "Midnight Train to Georgia" and groups like Kool and the Gang and The Chambers Brothers. Even though Ed's currently residing in the beautiful mountains outside of Durango, Colorado, he still keeps busy working on records at his home studio, sometimes traveling for sessions, and recently producing records by The Misfits and Joey Ramone.

You were in bands like The Psychotics, Men Working, and then Brandywine.

We were high school kids — all my friends. I have an early recording of one of those bands, Kenny and the Komotions, doing Jessie Hill's "Ooh Poo Pah Doo."

You were playing guitar?

Yeah. This was probably around '65 or something.

Where was this recording done?

In my parent's basement with one mic. Mono. I had a tape recorder. My parents got me one for Christmas. I took piano when I was a kid; but then a friend of a friend brought over a Gretsch Country Gentleman back in '62 or so. That's when I got interested in the guitar. My dad worked in the shipping department at Western Electric, the manufacturing arm of Bell Telephone, for 30 years. My mom worked on the assembly line for Johnson & Johnson. They always saved up a little bit of money and got me a really great Christmas present every year. In 1959 or 1960 I went to a New Year's Eve party with co-workers of my dad. I had never seen a tape recorder before — one of the guys was playing back music on it. He said, "Watch this." He rewound the tape, put on a blank tape, recorded my voice, and played it back for me. I was fascinated with tape recorders. I'd look them up in the encyclopedia, and I asked my parents for a tape recorder for the following Christmas. They got me a little Japanese 3-inch reel, battery-powered recorder. I got interested in guitars, and it went hand-in-hand. I had a guitar and a tape recorder, so I could record all of my bands. I hated school; I loved music. I was the guy who would figure out all of the songs, tell everybody else what to play, and write down the lyrics.

Were you recording to listen back and see how everything was coming together?

Just for fun. There was a thriving garage band community in Plainfield, New Jersey. I went to Essex County College for a minute, and then I worked at Union Carbide with chemical fumes and no masks. In the summer of '67 I went down to the Jersey shore and lived in the Seaside Heights area with a bunch of guys. I worked on the boardwalk at one of those game stands, where you try to throw the ball in or knock things over. Often when you won a prize it would be a record. Right down the street from where we rented our house was the guy who distributed those. I started driving around distributing the records for him, and as payment I would get albums. I was still in bands. Mike Bonagura has a lot to do with my story. When I was 15, he was ten. We'd practice at each other's houses. I met these people from South Plainfield through Mike, and I got into this band called The London Fog. Mike was in the band, and my good friend, Chip Miles, was the drummer. That lasted through the summer of '68.

Was the band gigging a lot?

We were always gigging. We did a lot of high school gigs. I remember getting my ABC [Alcoholic Beverage Commission] card so that I could play in nightclubs because I was under 21. There was a fellow named Barry Landers who managed The London Fog, as well as another band called The Cartoon. Some of the members mish-moshed; we got together and started being The Cartoon. There was some other band on Swan Song [Records] that Jimmy Page produced called The Cartoon, so we couldn't use the name. We somehow came up with the name Men Working. We actually had a session in November of 1970 with Men Working at MediaSound in New York City when it first opened. We got a demo deal with these original songs and signed to Richie Haven's label, Stormy Forest. Bob Margouleff was the engineer — he and Malcolm Cecil were staff engineers. They had the TONTO synthesizer in the room. There was a Scully 12-track at those Media sessions.

That's a format few people remember.

The 12-track? I think...