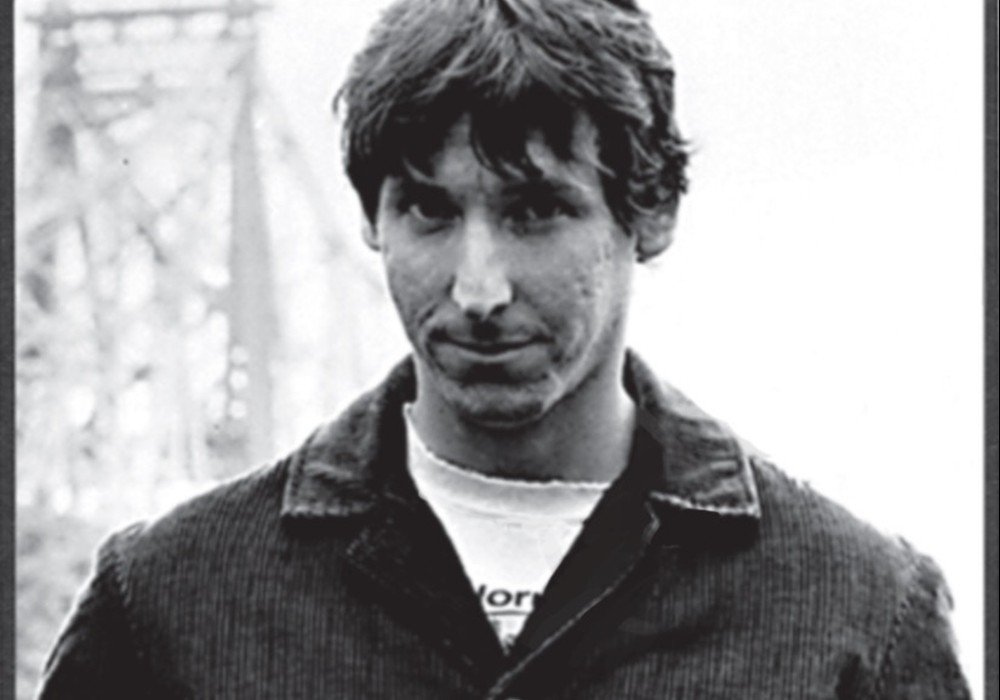

Between 1979 and 1998 Bob Mould put out 14 records with his two amazing bands, Hüsker Dü and Sugar, and five solo records, influencing the course of music with his enraged, swirling guitars and passionate lyrics along the way. After a brief stint in musical retirement, writing for the World Wrestling Federation, he busted back on the scene in 2002 to release three new records. All were released on his own Granary Music. I had the opportunity to sit with Bob before a gig to talk about running a label and his experiences in the biz. He was extremely thoughtful and kind, and, hell, he even bought me dinner. The first thing he said to me was that he reads Tape Op and really enjoys it. Things were looking good.

With Hüsker Dü you put your first single out on your own label, Reflex Records, then moved on to start S.O.L. [singles only label] and now Granary Music, again putting out your own records. What are some of the major changes you went through?

Well, going all the way from Reflex to New Alliance to S.S.T. to Warner Brothers to Virgin to Rykodisc to Granary music with starting S.O.L. being my own label in there as well. It went from vinyl to 8-track to cassette to CD to MP3 to nobody buying music anymore. [laughs] That's in the course of my career. When I started in 1979 music was a real important thing to everybody who was involved in it. And now we are in 2003 and music is now looked at as an accessory to other media, whether it is cable television, video games or movies. Music as a stand-alone device is not that important anymore in the grand scheme of things. It still is to true music fans.

Money is so much more the driving force now.

Yeah, in the early days it was, take out a loan at the bank, press up records, take 'em on the road and sell them at indie shops and right to the clerks who sell them at shows. Pay for gas and food that way. Then going to a big label where you get large advances and hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent to promote one track to radio stations around the country. To what I'm doing now, which is basically recording mostly at home, financing everything myself. Then I go out and either find a distribution deal to get records into retail or I sell them directly online using a third party as a storefront. So I've gone full circle over the course of it. Not quite the way I did it in '79 but it's pretty damn close. It's a labor of love and it's how I supplement my income, that and performing live and residual royalties from records over the years. I've gone through so many changes, it's a lot.

So with Granary now, are you a completely self-sufficient label where you manage yourself and book your own shows?

I am running the whole thing right now. I have an attorney I consult with on business matters if I am going to do a marketing or distribution deal with a label or a distributor, lay out different terms on how we are going to divvy up the money for that. As far as booking, I have a booking agent, Frank Riley, from a company High Road Touring in San Francisco that books all the way from the huge arena acts to somebody like me. I work in conjunction with him to put together tours that coincide with records, or if there is an opportunity to go and work on new material like I am now we book a tour. I do online sales through a company called MusicToday.com, which Dave Matthews and some of his people set up in Charlottesville. They create the storefront and do all the fulfillment for a fee. I license the tracks to a company called Cooking Vinyl located in the UK and they do a European pressing and distribution and promotion for me. They also license the stuff to Australia and Japan. So it's a number of different ways. So right now Granary is myself. Next year when I get ready to release some new active titles, I will probably bring at least one person on board to help out with the organization of things. Today I am dealing with three promoters coming up next week. I am dealing with the printer trying to get 11"" x 17" posters made so they can meet me at home in DC on Monday so I can get them ready for the set of dates. I was re-mixing some tracks on my laptop this afternoon. It's pretty much all day, every day, there's something to do.

On the artist side, what have you been doing lately?

Right now, the things I am working on are my next record, which will be out at the beginning of the year called Body of Song, which is a record I actually recorded with David Barbe [Sugar bass player, big time record producer and Tape Op alumni] and Matt Hammond down at David's studio in Athens. Some of it turned out good and some of it did not turn out good. I'm still combing though it, trying to make a good record out of it. In D.C., I am working with a friend of mine named Richard Morel who is Deep Dish's engineer. He's done a lot of re-mixes for everything from New Order to Yoko Ono to Mariah Carey to t.A.T.u. to whoever. He and I are writing a record together under the name Blowoff. In addition, Rich and I DJ. We have a DJ night once a month in D.C. that is a real big deal to a lot of people. LoudBomb is an electronic project. Its like my alter ego and was meant to be a studio project but about month ago I put together a live gig where I was playing bass and DJ-ing, and I had Brendan Canty and Jerry Busher, who are the two drummers from Fugazi. They switched off between playing drums and guitars, some workstation stuff. The three of us took my root base recordings and sort of made a live thing out of it as well. Those are the main things I am working on right now.

Hearing Ian MacKaye talk at the Tape Op conference, he spoke of how the community of music in D.C. is really strong and it sounds like you are part that community as well.

Ian is sort the central point for everybody in the D.C. scene with Discord, and he is actually getting his face on a building not too far from where I live that he is going to use as a community center. There is all kinds of stuff. From Positive Forests to Fort Reno Concerts to the stuff Ian puts together. There is a lot of good community there. You know there is also really a great electronic scene that I don't think I am so much a part of like Deep Dish, Thievery Corporation, my friend Aaron Hedges. There is a lot of DJ s and re-mixers there as well and we're all starting to try to do a lot more cooperative stuff.

You have been producing records since the Hüsker days, and now you're engineering and producing your records. What steps do you take as a producer when working with other bands?

I just like working on projects I feel passionate about. As long as the music is speaking, whether it's my own stuff or somebody else's, that is the main criteria. As far as producing other bands, t. hat's a lot. That's going to the bands and question[ing] them on what they are trying to do with their songs. Question[ing] them on what effect they want to have on people with their music. To helping them book their travel, helping them book their studios to all the things besides sitting in the room saying, "Do it again," or, "Don't do it again." Sorting out the appropriate engineer, figuring out what kind of equipment we want to use. Whether we are going to go analog or digital or a hybrid, all the way through signing off in the mastering session.

Mastering can be done so many different ways these days. How do you prepare for mastering and how do you go about it?

I think it really depends on the type of music. If you are recording an organic project, analog tape, I 'd rather use really good tube compression or SSL compression. To create an analog master that I walk in to master with, a lot of times I still go in with a ½" tape. Actually, I almost always do. Recently I have been going in with AIFF files, bringing them up in Pro Tools and working off a Pro Tools rig and then into Howie's mastering rig. For electronic stuff there's something to be gained by going to some analog transfer. For modulating my most recent record, I did most of the work at home in Digital Performer and then went to a studio and rented a rack of Neve 1064's, started out putting everything thru the 1064's and then to tape, and then bringing it back into the computer. And what happened was I starting picking up that depth of field that digital sometimes just doesn't have. Digital to me is very wide format and analog is a deeper format. Now, having spent more time working with digital I have learned how to emulate that better, so I don't know if I am going to go through all those steps again. There are different ways to get where you want to go and [it] really depends on the source material.

I noticed you work with Howie Weinberg to master all your records over the years. How did that come about?

I used Howie for just about everything. There have been a couple records recently [where] I've used Jim Wilson, who was my engineer in Texas. Jim has gotten to be a quite a good mastering engineer. Howie has been my go-to guy for the last fifteen years. He did a lot of records I liked. The early New York stuff, the Clash [Give 'em Enough Rope]. The Beasties — all their stuff, Sonic Youth. We all used him for mastering. Howie's got a good set of ears and good intuition, so it was always a pleasure to work with him. He is a legend, he's the best guy, I think, in the business. That being said, Jim Wilson is amazing and there are a lot of young guys coming up. The technology has changed so much in the last three years for mastering.

Granary6 is your studio. Is that a home studio?

Granary is always a home studio. The number just designates where I am living. It just goes up in numbers. [laughs]

You said you have been using Digital Performer at Granary6 to track. What other toys have you got at Granary6?

What I got at home, the core is using the Power Mac G4's, whether it's my laptop or dual gig tower I got. Pretty much use Mark of the Unicorn transformers and a couple of Yamaha O2r's that I leave everything plugged in and set up so I run everything through them. I actually like the sounds of the pre-amps in the O2r's. They are really brash and crazy sounding. I got a couple Pultec blue faces, a Pultec silver face, I've got some of Geoff Daking's original EQs, four of the upright A range emulators in a military case, so I have been familiar with Geoff's stuff for a while. I've got an old Drawmer 1960, some Tony Larkin stuff, a Coles ribbon mic. I use a 414 CL2 for almost everything, vocals. It takes the honky-ness out of my voice without having to go to the EQ so quick. I also like really shitty compressors, like the cheap dbx 166 rack mount. When I am doing all my filter house stuff — you know, Daft Punk-sounding stuff, the cheaper the compressor the better the sound, cause you get that totally trashy up-front sound. Software-wise, Digital Performer, I use Reason Live and Recycle quite a bit. I've got some old synthesizers, old drum machines. But really, I can do almost everything inside of Reason now because they've got every sound that has ever been made with a drum machine. And it's much easier for me to program. I use a lot of plug-ins. I use the DUY plug-ins. It's a Spanish company I think. They make some really great maximizers. When I am mastering, I pretty much take a track and maximize it so far out it picks up a really bizarre, heavy sound that I can't get with outboard gear. It's just number crunching instead of signal path. I've got vocoders and auto-tuners. Gimmicky stuff that's fun, that gives you a different kind of sound. But I use a lot of the DP built-in plug-ins. I get everything I really need out of that. Digital Performer, Reason and Live are the three packages I use to create things.

Your new records are electronic-based. Are you creating the samples yourself or are you bringing them in from another forum?

A lot of kinds of things. A lot of it is sampled, organic instruments. A lot of it is stuff I shouldn't be using because I didn't get clearance, snippets off of records. But, hey, whatever.

A lot of the snare sounds are really warm and then will switch several times within a single song.

A lot of that going on, a lot of flipping through sounds. A lot of that is in the sensitivity-based programming. With Reason or with anything you can put randomness in the velocity of hits, and it makes it feel more natural. With a lot of that I played live cymbals and live snare along as well and I will swap it out. So I do a lot of different things. But I think any sound is good. I sample off of Iranian pop radio over the Internet and throw that in there too. Anything that gets the job done. I'll use stock loops, you know, cleared loop sets, if I need to get something. It doesn't matter anymore, I am not a purist. Anything that gets an emotion across, I will use it.

Are there any tricks or secrets you've discovered to get new sounds you couldn't have before while making the new records?

So many things. With a program like Live, for instance, where you can drop a sound in and do real-time time stretching on the fly. There is no excuse not to be able get the most unique sounds possible these days. There is really no reason anything should ever sound the same twice. If people haven't had any experience with a package like Live they should really take a look at it and see how deep they can go with manipulating sounds. It's really mind-boggling. It's really hard to get out of it once you gotten in it.

Your acoustic sound, even in the Hüsker records, through Sugar and the solo records, has the most distinctive sound. Every time I heard it I knew it was that same guitar. It is double tracked often, but there is still something there, some sort of brightness. I have always wondered how you got that sound, if you wouldn't mind talking about it.

It's the guitar. It's the Yamaha APX. It is this real thin, wood guitar with a heavy plastic back. For some reason the way I got it set up, it just sounds like a bag of dimes being shaken all the time. That's the idea, is to keep all those high harmonics as active as possible. You'll see tonight.

Now that it has been 24 years in the biz, what do you look back on as your most positive experiences in playing, engineering or producing?

To me, it was the making of Copper Blue and Beaster. Those two records were made at the same time. I did those with Lou Giordano [former Hüsker Dü sound guy] alongside. We were splitting all the production and engineering. Lou and I have a good rapport. He is a great guy to work with, someone I could really trust on the other side of the glass when I was in doing the artist side. And he wasn't uptight when controlling the board during mixing, which is really important to me too, because I like to get my hands on everything. It's sometimes easier for me to do it than to explain it. I just think that was such a prolific period for me, and really strong material to work with. They couldn't help but be the records that they were. The year or so after Hüsker Dü broke up when I wrote Workbook, I thought was a really great year for me, just woodshedding and revisiting the guitar. Being able to work with Anton Fier and Tony Maimone, two guys I got a lot or respect for. I'm really proud of Modulate. That was a completely self-made record with no help at all, and it shows. [chuckles]. It could have been slicker. I did that record completely from start to finish from home. I had a little help from an engineer up in Woodstock, mic'ing up my mouth so I could sing up there. He is a good engineer and helped out with some other stuff, but really I am really proud of that record. There has been a lot of great stuff over the years. The Hüsker stuff, I was learning through all those years. It was all trial and error. Zen Arcade — I sort of knew what I was doing by then, really started to take control of the sound of things and the direction of things more, f. or better or worse. I think it was for the best. A lot of good experiences along the way. Learning from a lot of people. Working at the Power Station during Black Sheets of Rain with Steve Boyer, who is a great engineer, and just working in a room that was that state of the art. Learned a lot about acoustics and sound, how much is too much. A lot of great learning experiences.

Black Sheets of Rain is one of my favorite records. After Workbook it was just so strong and aggressive and heavy. I always wondered about that recording. What was the driving force behind that energy?

The songs were a little more delicate than the record shows. I think the record is that bombastic because Tony and Anton and I had been on the road all year headlining or playing with the Pixies or whatever and we just kept getting louder and louder and louder. When it came time to make Black Sheets there was just no way to turn it down. We built ourselves into that spot. In hindsight, that record could have been a little more delicate and I think it would have been a better record. But, hey, it was a good loud record.

With Zen Arcade and several other Hüsker records, you worked with Spot. What were you tracking to back then, were they live recordings and how much processing of the signal did you do during mixing?

With Spot, he was a real purist. His background was jazz, so his theory was, get the right mic on the finely tuned instrument and go with it. Learned a lot from Spot. Those records are mostly first takes, top to bottom. The Hüskers were a really tight live band, so we could just walk into a studio and just bang through the stuff and get it done really quick. Processing — I used a little bit of a harmonizer on my guitar to get that warble on things. He pretty much liked it straight up. A little compression on things, but not a whole lot of effects. After Spot, I started experimenting with some things like the gated reverb, which was pretty eighties. Spot was a great guy. I mean, it ended sort of blown off kilter. I think we wanted to go a different direction than Spot was going but when you are young you don't articulate things in the best way. In the intervening years, Spot and I lived in Austin, Texas at the same time in the nineties. We hung out played ping-pong, drank coffee. There's no heat there between he and I. I think the other guys in the Hüskers had a problem with him, but Spot and I are pretty good friends. We talked about [it] and said, "We were all stupid then."

You have been on every kind of label there is, from the majors to your own labels and all in between. What do you see as the big differences, and what is your preference?

On my own label, I call all the shots on how much money I am going to spend promoting a record, what direction, how the whole thing gets laid out, hiring a publicist, hiring radio promotion people and all that. You go to a major and all of that stuff is built into the deal, they got promotion, publicists, marketing people, all that. And of course they have their own ideas. For all the money a major gives you and all the perks, you give up some freedom. On a label like Rykodisc, it is the best of both worlds, but there are some problems with it as well. You know, I think that just runs the gamut. When you're doing it all yourself you're completely in charge of how much liability and how much exposure, how much financial exposure you are willing to accept. On a major everything's paid for. Having said that, you will never get your masters back. That's the trade-off. You get that kind of money, you're giving it away. It's like working at Factory Town Mortgage. You work in the Factory Town, you buy the house, but Factory Town holds the mortgage.

I read a couple years ago how you wanted to get My Bloody Valentine back together to get another record out of them.

I would love to work with Kevin Shields. But I doubt they will ever put their project back together. Kevin was just so far ahead of the curve with what he was doing. The whole loop-based, droning, heavy thing. That set the tone for everything that came right after and now I think people are revisiting that.

I think it is bigger now than ever.

Absolutely. He was just so far ahead of his time it wasn't funny. I would love to get a hold of Kevin and do some sort of studio project with him. So him and Hakan Lidbo would be the two things. But rock bands — I just don't know if I like babysitting anymore.