Would you first give your definition of mastering and why it matters?

Mastering is the last creative process in the chain and the final technical check before duplication. Creatively, an artist can wait until mastering to edit songs, adjust fades, sequence and the spacing between the songs. Generally speaking, the goal is to make it as easy as possible for the listener to get through the CD without needing to adjust playback volume and EQ. This is accomplished with equalization, compression and/or limiting. But equalization and compression can also be used to change the character of the recording. In the right hands, mastering can transform a collection of good mixes into a great album.

How did you become interested in mastering?

I was always interested in the process and attended the mastering sessions for every record I recorded. In the beginning when I was struggling to make a good-sounding record the mastering session was my last hope to fix all the shortcomings in my work. Although I was working with some of the most skilled mastering engineers in the world, like Bernie Grundman or Bob Ludwig, I soon realized there was only so much they could do. Each time I asked questions, took notes and observed what they where doing or not doing. I would apply that knowledge to my next recording project.

How did you decide to change careers from recording to mastering?

It wasn't until 1997 when I decided I wanted to start mastering smaller projects myself. Things had really changed in the way CDs were being mastered and computers didn't intimidate me. Plus, knowing how to cut a lacquer was no longer necessary for mastering CDs. I started fooling around at home with the first version of Pro Tools... mastering demos and even, I'm afraid to say, a few CDs for friends. I was still going to the big guys for the CDs I was working on, but the gap was beginning to narrow and I found myself saying for the first time, "Hey, I can do this." I was also tired of living from gig to gig as an independent recording engineer and working out of town away from my family. I had become typecast as a "guitar" engineer because of my success with Satriani and was being asked to make the same records over and over. But I had no reputation as a mastering engineer, no real mastering equipment or a room to put it in if I did.

How did you come by your first mastering studio?

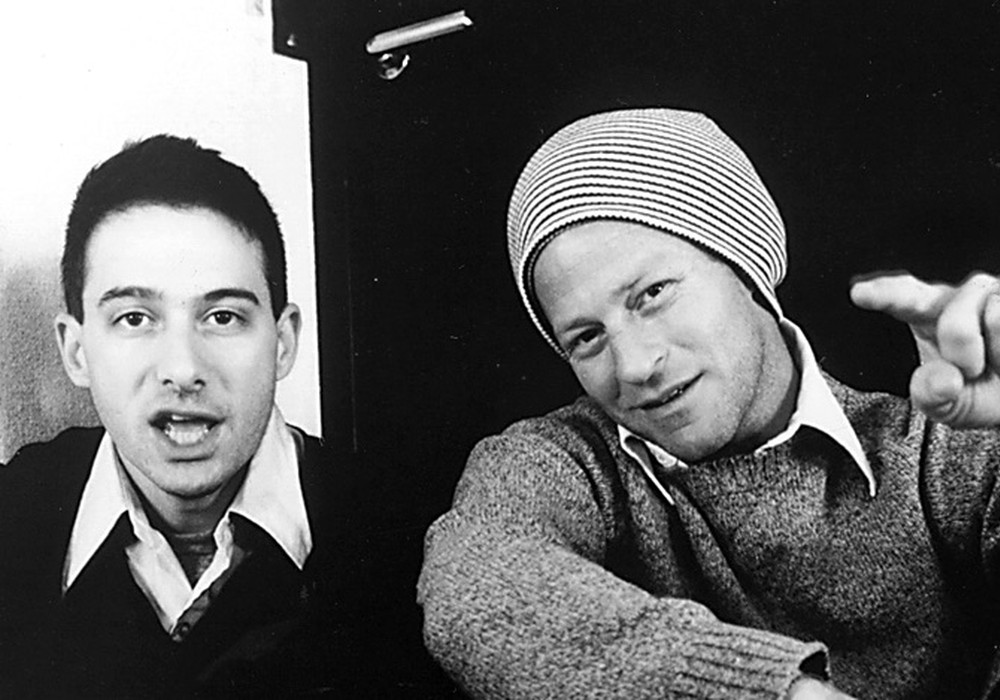

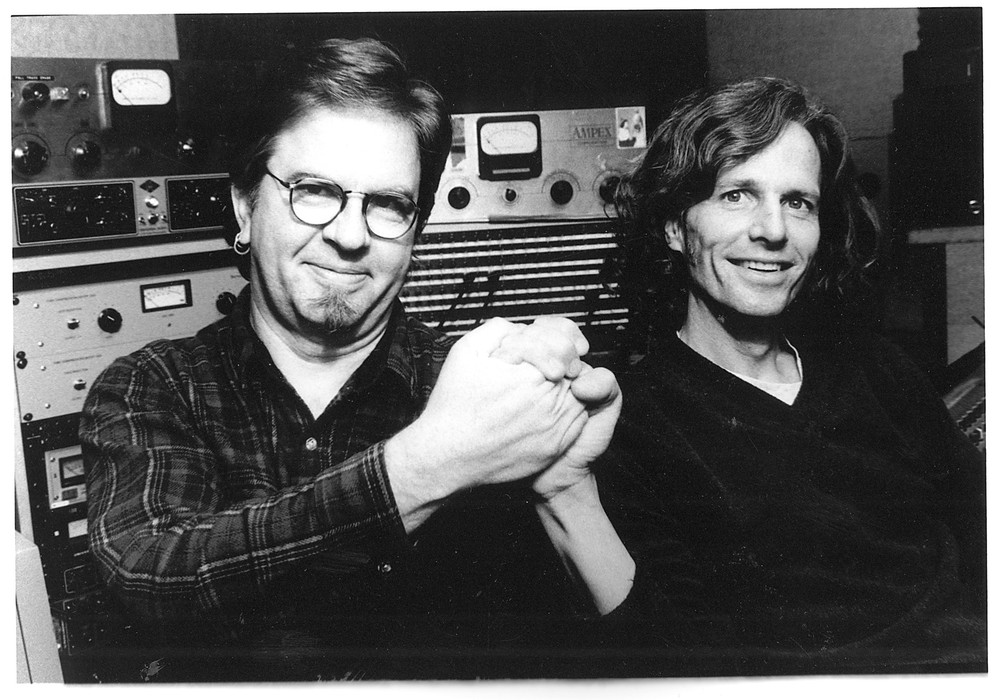

In the mid '90s there was a mastering studio in San Francisco called Rocket Lab that was doing a very good business. They had a small room, nice equipment and some very good engineers. The owner, who I'd known for a long time, invited me to join the staff, develop my mastering skills and hopefully build a reputation. But within weeks of the offer it was announced that the business was losing its lease, and, since the owners had no plans to move the business, I needed another plan. It was around this time I got a call from The Plant Recording Studios in Sausalito. They needed someone to oversee the wiring of their new surround mixing room called "The Garden". I accepted the job. While I was there, I asked the owner, Arne Frager, if he would ever consider building a mastering studio. He told me that he had thought about it but knew it took a mastering engineer with a reputation to make it profitable. I sat down and created a business plan that was modeled after Rocket Lab, but with a much bigger room and all new equipment. To hedge my bet I asked one of Rocket's former engineers, Michael Romanowski, if he would like to work at the new studio and he agreed. I went back to Arnie at The Plant and presented the plan and he accepted. It was good timing that Rocket Lab had closed, The Plant was in an expansion mode and Arnie had faith in me to pull it off.

How was it starting out?

At first I wasn't all that confident in what I was doing. I had to learn how to use the SADiE mastering software on a PC and appear like I knew what I was doing. It was my perfectionism and attention to detail that saved me. I would check and double-check everything I did. Even after the client left I would continue to work on it until I was satisfied. It is a huge responsibility to master someone's CD and there are many ways I could've messed it up.

How do you handle the raw nerve endings of your radically diverse clientele?

I treat every client the same, regardless of the type of music or the quality of their work. Everybody pours their heart and soul into their music and everybody's emotionally attached. It's a big deal for them and I totally relate to how they are feeling — I used to be them. By now they're aware of every little flaw and in most cases anxious about hearing it in a mastering room. They often look to me for affirmation and in some cases want my opinion on their songs or singing. I can always find something I like about it and don't hesitate to tell them. Bernie Grundman is brilliant at making you think that you just brought in the greatest record he ever heard. Not with BS but with enthusiasm and caring. I try to provide the same thing.

Do you encourage the musician to be at the mastering session?

Yes, I think they can benefit from being there. If there is editing to be done or fades they want a certain way they should be there. But if a bunch of people come that have nothing to offer and turn the session into a party it's very distracting.

Do you kick them out?

No, it's their party, it just takes me longer to do my job. That's why mastering studios charge by the hour.

Talk about your equipment and methodology for mastering...

I use a SADiE digital editing DAW and love it. It's designed for one purpose: mastering CDs. I have all the groovy gear you would expect to find in any high-end mastering studio. Stupidly expensive converters, old analog tube gear and everything in-between. It's enough gear to ruin anyone's CD. My favorite piece is my Crookwood mastering console. It's custom built and allows me to route any piece of analog or digital gear where I want in any combination with a push of a button, no patchbay. This allows me to quickly try different processors when trying to solve a problem. The way I work is like this: I first listen to what the client has brought me to get an idea of what I have to work with. I will also try and get a feel for what their expectations are. I then decide what equipment and in what order to use it. By nature I'm a minimalist and only use the gear I need to get the results. If the source material is digital I may stay digital or opt to convert to analog for EQ-ing, then back to digital for leveling. I load everything into the SADiE DAW at 44.1/24-bit and avoid any sample rate converting. If I receive an all digital recording of, say, a rock act that has lots of distorted guitars and crashing cymbals I'll transfer the recording to 1/2" tape at 30 or 15 ips, then master from the tape. It really helps the top end by smoothing it out a bit and making it slightly less "digital" sounding, plus the client now has an archived analog master of their project. After the processed material is in the computer I'll trim the head and tails, add fades if necessary and then put the tracks into sequence. Then I sample each track and make sure the apparent level is consistent across the CD. If one is too loud I return to the original source and re-master it with less limiting. If it's not loud enough I add additional limiting 1 dB at a time. Then I put in the spaces between the songs. Almost every client asks me if there is a standard spacing. The answer is no, but two seconds works most of the time. I go through each transition and check the feel of the timing and make adjustments. Sometimes I start the next track in time with the last by counting out two bars or so. If there is a mood change, say a heavy up-tempo song that ends abruptly and is followed by a ballad, three seconds works better. After that I ask SADiE to automatically generate the track IDs. If there are cross-fades I sometimes manually move the start IDs to minimize hearing the end of the previous song when selecting that track. I then make a reference CD-R that's dithered to 16 bits by the POW-R plug-in for the client to review at home. If the client requests a change I make the change and burn another reference until I get approval to make a master PMCD. Then I ship the master directly to the duplicator. Everything gets backed up on AIT tape so I can restore the project and continue work if the client returns later. That's not archiving. To archive I recommend analog tape.

What's wrong with digitally archiving audio?

Analog tape has proven to be playable after 50 years. There are thousands of tape recorders in the world that will still be usable for many years to come. I have DAT tapes now from the '80s that won't play. People using computer software that changes every six months are in for a rude awakening ten years from now when they want to do a re-mix, forget about it. All these FireWire drives that are so popular if stored for long periods of time won't even spin up, assuming you still have the software to talk to them, it's a real problem. I just transferred Joe Satriani's last three albums done on Pro Tools to analog 2" tape. We realized when we were working on his Anthology CD for Epic that we were using tapes from 1986. Twenty years from now I don't expect anyone will be able to play a Pro Tools 6.2 file from Joe's FireWire drives.

Aren't you worried your mastering skills will become redundant since everything can be done at home in the computer?

There'll always be exceptions to this rule, but I believe it's important to turn the project over to someone who can be objective. By the time the CD is mixed everybody is pretty burnt out and may be sick of hearing it. Not a great state of mind for a mastering engineer. In fact, I rarely master the projects I engineer or mix for just that reason. Recording studio control rooms in general are not designed for mastering. Compromises have been made in the room's acoustics to facilitate the console and recording equipment. They are also too noisy to hear small details in the recording. A mastering studio should be dead quiet and look and feel more like a living room with a nice set of full range speakers. Also, equipment design for mastering is different than recording equipment in a number of ways.

Different in what ways?

Most analog recording gear is designed to work on individual tracks rather than stereo tracks. A two-channel equalizer for recording will not work well as a mastering equalizer because the gain adjustments won't track the left and right channels and perfectly shift the stereo image. You can't just set the left and right variable gain knobs to marks on the faceplate and expect it to be spot on. Analog parametric equalizers are even worse. How do you know that the left and right channels are both at 5 k? When you boost, say, 2 dBs at 72 Hz, you don't want the bass guitar to drift to one side of the stereo image. Mastering equalizers have 1/2 dB stepped gain adjustments using matched components. They also have many fixed frequencies that are precisely matched. Stereo analog compressors can also be a problem if too old or not well designed. Many of them will drift off center as more gain reduction is applied to the two channels equally. If you're skeptical, try putting a 1 k tone into your favorite compressor, add 6 dB of gain reduction and compare the left and right output levels. One of the nice things about plug-ins is this is not an issue, though they may have other issues, like the way they sound.

What about the way plug-ins sound?

Like any gear, some is better designed than others. I've been impressed with the plug-ins by Universal Audio, Massenburg and the Sony Oxford series, so I know it can be done well. It's no accident that these three companies also made some of the best analog gear ever. In my SADiE mastering DAW I only use the CEDAR de-noise, de-click and the POW-R dither plug-ins. All other processing is outboard.

What's your take on the mastering loudness wars?

Like most mastering engineers I think it got out of hand. I don't participate unless a client demands it. The funny thing is, most don't anymore. Five years ago every band wanted their CD louder than the last one. It's a guy thing. Now they want it to sound better than the last one. I guess we needed to get it out of our systems.

Okay, let's talk about audio quality: Analog vs. digital?

They can both suck. Go into any used record store and you'll find thousands of dreadful sounding analog recordings. I know, I made a few. Go into any new CD store and you will find thousands of lousy sounding CDs. I made some of those too. The point is, it doesn't matter. What matters is how you react to what you're hearing and what you do about it. Being a good engineer is knowing how to solve problems. The longer you work at it the more skills you develop, allowing you to quickly identify a problem and fix it. Anyone can stick a mic in front of a singer and press 'record'. It's the 20 other little problems that take place when they start to sing that will make or break you. Having said that, there is very well designed recording equipment, both analog and digital. It's up to the engineer to decide what's what and when to use it. The "state of the art" digital is quite amazing, totally transparent and faithful to the original source. The thing about analog is it always brings something to the party. On the high end, it can also be very close to the original source. But it's most admired for the coloration it provides by its so-called technical shortcomings. I use a mix of both. There are times I want transparency and don't want to alter the sound, often the case in mastering. Then there are instances where I use the analog device to enhance the recording, like using a nice tube mic preamp. In the analog domain there's a huge pallet of color to choose from. A recording made on a vintage Neve console sounds totally different than one made on an SSL. With digital it either sounds transparent or it doesn't. If it doesn't, that ain't a good thing. Because analog has been around for over 50 years we've had a lot of time to do it right. With digital we're forced to use it in its infancy, which helped give it a bad rap. The latest generation of DAWs operating with high sample rates and 24-bit word length is nearly to the point of total transparency. Due to their editing capabilities they're dominating the industry. But a skilled engineer can make a great sounding recording on anything.