There was a very innocent time, before I could drive, but I'd already discovered the odd record store, the odd 'zine and most importantly the left-of-field band. My mom would run an errand with me in tow, off to the record store, usually looking for dance 12 inches of bands like Depeche Mode, Duran Duran, or Skinny Puppy, Fishbone, whatever. I was probably 13 or 14 and it was the mid-'80s. I remember reading somewhere about this band called the The, and even hearing about them when Joan Rivers asked Duran Duran who they liked in music those days. What I can't remember is whether I picked up Soul Mining on my own, or if it was because I heard the ultra-cool record store dude talking about it at the counter. Either way, I bought it and loved it. It's a tasty mix of electronics, acoustics, and synthetics, with intense and often beautiful vocals. Didn't see it that way then, I just thought it was cool.

Flash forward to the October 11 2000 — the 21st century: the The have released Infected, Mind Bomb, Dusk, and a covers record called Hanky Panky. I've since gotten into this world of recording, touring, music and I'm completely about to pass out cause Matt Johnson's on the other end of the phone and it's 10 AM. He had a new record out then called Naked Self: a dark, earthy, Lower East Side meets desert dirt and a stumble out of a generic pub through wet, English cold to who-knows-where.

How did your relationship with the studio begin?

I left school with no qualifications at all. I didn't enjoy school, I enjoyed being with my band. I then wrote off a letter to loads of recording studios. I got the job, started as tea boy, coffee boy. I absolutely loved being around the studio, the tape, the smell of the tape, the smell of all the equipment. When we started there it was very well run. It was very old fashioned in a way, prided itself on the way it trained its engineers. For the first few months I was strapped with an old tape recorder, like an old EMI tape recorder, learning how to edit tape with this big, old pair of headphones on. They put me on gack — the tape you just chuck away — and I would get different angle editing blocks, practice with that, re-leader, this and that. Then after a few weeks of that I graduated to leadering up actual master tapes. But you really had to learn it properly, and tidying up, how to tie cables up, how to keep the studio clean and tidy. I own a commercial studio in London and sometimes go over there when I'm in London and come up to the assistants and say to them, "We're going to have a little tidy up," and they'd just laugh at me. It's a completely different thing, they've got their feet up, none of them want to do any work. Every Monday you'd have to clean the machine, get the isopropyl alcohol out and tidy... clean all the cables. It was a really old fashioned, well-run little studio ' 8-track actually. They had a big-old Ampex and a Trident desk, and they really taught you well. Younger people today really want to play with their samplers and be producers. They don't really want to learn it from the ground up anymore.

I think we're a far cry from the days where people were wearing lab coats.

In fact I'd even had the idea of making my staff in London wear a lab coat like the old Abbey Road thing. I love all that old stuff, it's like the old laboratory... but then again they were a bit tight, those guys. They didn't really wanna push the equipment, but there is a sort of nostalgia for that era in a way. It was really different, people really did learn their trade from the bottom up.

Do you feel like your relationship with the studio is such that it's like another instrument?

I've always been reluctant to describe myself as a musician in a lot of ways. The Brian Eno phrase "the Non-Musician" — in the late '70s he coined it — really resonated with me because, like I said, my passion was sound and tape recorders. I loved songwriting and I loved guitars, but I never practiced scales. I couldn't go and sit and hear another band playing their songs. I'm a singer songwriter to start, and the studio is my instrument. My hours were spent locked in my bedroom playing with tape recorders creating my little tape loops and stuff like that. "Musique Concrete" pieces, that's where my passion was, so I've always seen the studio as an instrument. Maybe now more than ever, it's incredible what you can do.

Mind Bomb is an impeccably recorded record, specifically "Armageddon Days... "

Yyyeaah...

Back in those days it seemed like there was an urge to push the studio technology into this wild largeness... do you feel that you are going in a reverse direction from that now?

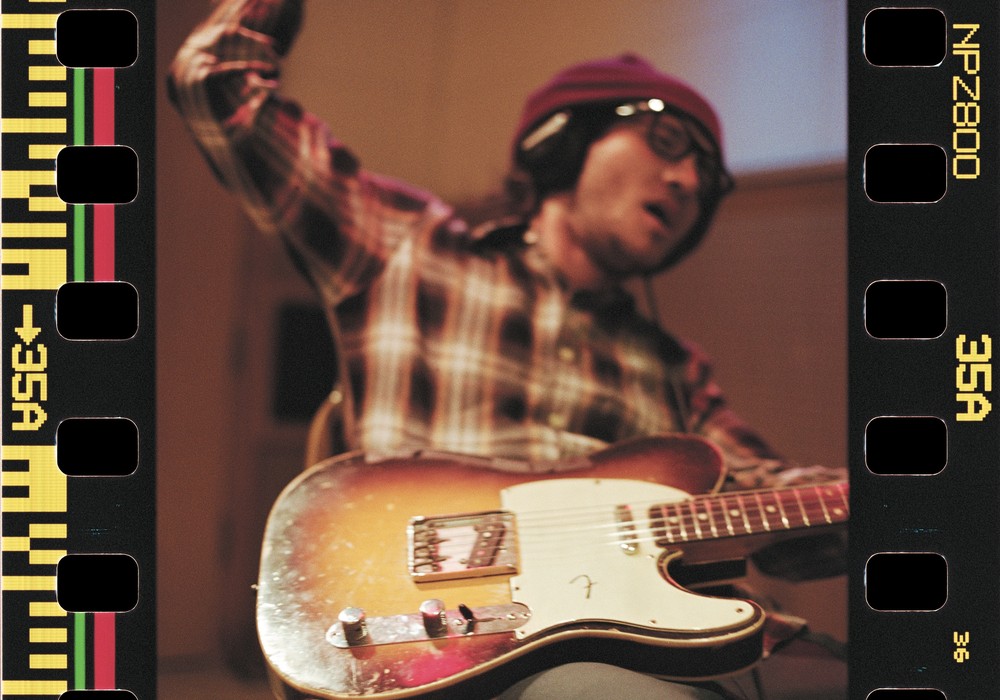

Possibly with this album. I have to give a lot of credit to the people I worked with as well. I collaborate, and I'm producer/co-producer. I co-produce the engineers and in that case it was Warne Livesey and Roli Mossiman. So they have to take a lot of credit for the sonic quality. Even though I'm driving, it's my vision and I'm pushing them. I've been very fortunate to have worked with some very talented engineers. Often very underrated in our profession, engineers. I would say that, because in those days you really had to be much more imaginative in the analog world to come up with new sounds. Nowadays we have Pro Tools systems. There are so many possibilities. You're able to zoom in at almost a cellular level. With this album, I wanted to go back to a sort of linear approach — sixteen tracks, analog. There's no reverb at all, I just used tape echo, no keyboards. I didn't use digital tuners, I actually used tuning by ear. If you listen to a lot of old records, the instruments are slightly out of tune, but it gives it this sort of natural oscillation. With digital tuners, things get a bit sterile. It was a purposeful decision to force myself to make decisions as we went along instead of saving those decisions for the mixing stages. Saying, "Okay you have to be decisive, you have to know what you want for the song." And I do enjoy working in the old analog, linear fashion, as much as the non-linear, digital way. And I do think the two can coexist quite comfortably. This particular project definitely suited that. The kind of atmosphere that I wanted' riding the subway writing lyrics in the middle of the night I wanted something gritty, raw, and a bit sort of bursting out the speakers rather than polished and clean.

Do you think that your move to Chinatown and that mindset lent itself to the overall sonic quality of the record?

Very much so, that earthiness. I like living abroad, but particularly in Chinatown all the signs are in Chinese, and a lot of people speak very little English, you feel more foreign than you would imagine. We did pick up some interesting Chinese equipment. There are some stores that have lots of this old industrial equipment. I saw what looked like some recording equipment. Initially I just wanted to take some photographs of it for the sleeve, but I did some investigating of it. It was from some old radio station in, I believe, Shanghai the guy said. It was his father's equipment and he didn't want to sell it, but we took some of it down to the studio and I put a disclaimer on the sleeve because there's some of that distortion, but it gave everything this really interesting sound. I don't know what the equipment was called cause it's all in Chinese. We messed around with it. I'm sure just that sort of atmosphere' being in Chinatown at that particular time, the record wouldn't have sounded the same if we did it in London.

What sort of equipment did you find?

It was like mic pres, it was mostly from a radio station so it was like compressors and EQs. It was primitive — ya know — I think they copied old American designs, I suppose, like tube stuff, just ripped off the old American designs. It was primitive and harsh. It sounded good.

What kind of console was used on this record?

We used an old API — we used a couple of things actually — used some Neves, this old little API, I can't remember the name. It was an old broadcast mixer. We recorded at Harold Dessau's studio, which sadly is no longer there. I always referred to it as a mini Brill building, half-a-dozen songwriters had little offices in there. I had an office there. A bunch of other musicians would come and practice around there, it was such a lovely atmosphere. It's a converted building, wooden floors, high ceilings. You would think it was the wrong place to have a studio but there's a fantastic atmosphere with dark light, heavy velvet curtains, lots of old equipment, old tube compressors, Neve, API outboard gear, and a Studer 24 track machine. Oh, there was an Ampex there, a 16-track with one of the tracks not working. It was this huge old Ampex that sounded fantastic. We mixed it at Greene Street on the API Legacy. I think the Greene Street one was one of the first ones' fantastic little desk.

They've got some nice little secret parts in those machines. Those old op amps.

Yeah! We recorded some things at Greene Street as well' wonderful sound: API with some Neve, Ampex machine, and mixed them to Studer 1/2" tape.

It's a good formula. It's nice to hear that somebody's working in that realm. Everything else is Pro Tools and people are talking about this being the end of the 2" machine as we know it.

I know... Growing up with this, I've always had a love for tape. We'll get to the point where the next leap will surpass analog and you'll be able to emulate analog very accurately, I suppose it's inevitable. But at the same point, there is something to working in a linear way with old equipment. Maybe it's nostalgic, but it's very tactile. It's a nice pace of working. Even when you'd rewind the tape, you'd be thinking about it. I used to like that time when you'd come in from a take and they'd be rewinding. It'd give you a minute or two to pause and think. Just little things like that that would change the rhythm. Also the other thing that people don't think about with these digital workstations like Pro Tools — and Pro Tools is fine, I have a system and it's incredible what you can do with them — but in some ways, [you] start to look at the sound rather than listen to it. Before, you'd be in the studio, the lights would be blinking and your focus would be on the VU meters or your eyes would be closed. Now you're looking at waveforms. The computer is like a television set in your home, it becomes like when you'd sit by the fireplace and have a conversation and the television arrived and dominated. At the studio it dominates. I'm wondering whether it detracts from our hearing, from the aural senses in some way, the visual sense is now becoming quite dominant in the studio.

I read that you are using three microphones on tour. Is that true?

Yes it is. Well I always used to do that. Anyway, I had a couple. This time I've got 3, and I had a mic stand custom built because it was always awkward using 3 separate mic stands. I've always used a lot of distortion on the voice, either in the studio I'd run it through amplifiers, or for the clean sound I'd use limiters, extreme limiting on my voice and rather than let the soundman just' it seemed to be easier, not really easier, but it gets to a point where you need 2 microphones to get the right sound rather than plugging around with the same microphone to change the sound. But also visually, it's kind of interesting as well. It's always made sense to me because I've always messed around with the vocal sound. John Lennon was someone that always sort of messed with vocal sounds. I love old blues singers like Howlin' Wolf, that natural overdrive, distortion and compression, and that's something [I've done] since my very first record 20 years ago' that kind of distortion.

That's something I've noticed about your records. It seems like you have 3 very distinct approaches: there's one that's totally in your head, that very clean sound.

Yes!

And then the very distorted megaphone sound. And more recently that rock-a-billy, nice tape echo sound.

Yes, yes, I love the old tape echo sound. There's the ultra compressed vocal sound where I'm whispering, almost.

www.thethe.com

Interviews | No. 93

Steve Lillywhite: U2, Peter Gabriel, XTC

by John Baccigaluppi

Near the end of my interview with Steve Lillywhite, CBE, he confessed to me, "My first thought is that I hate doing some of these interviews. I thought Tape Op was like the other audio magazines, and...