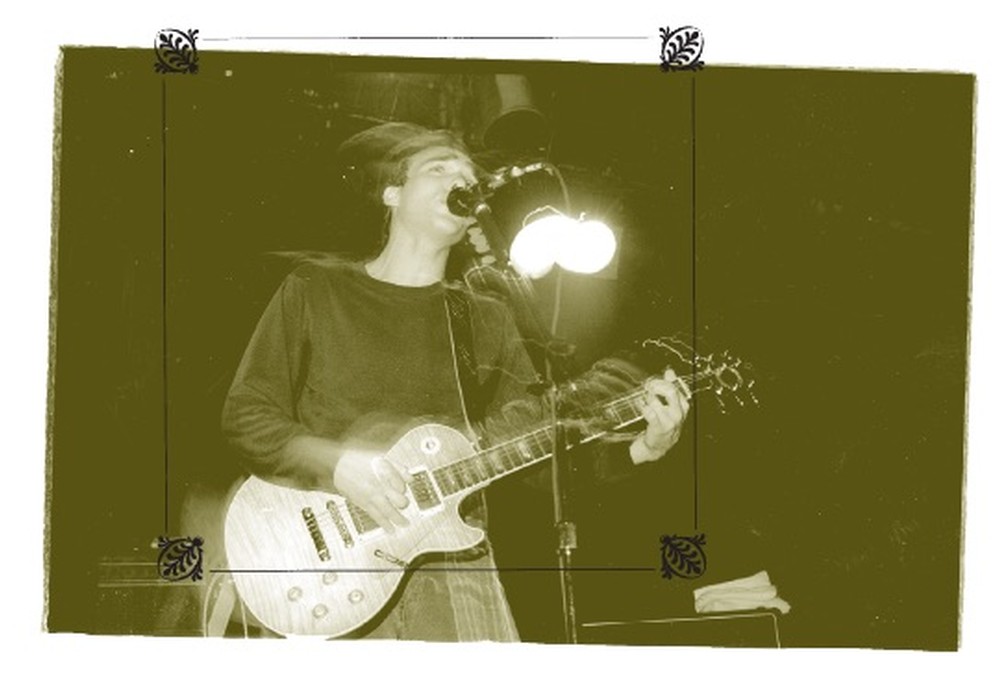

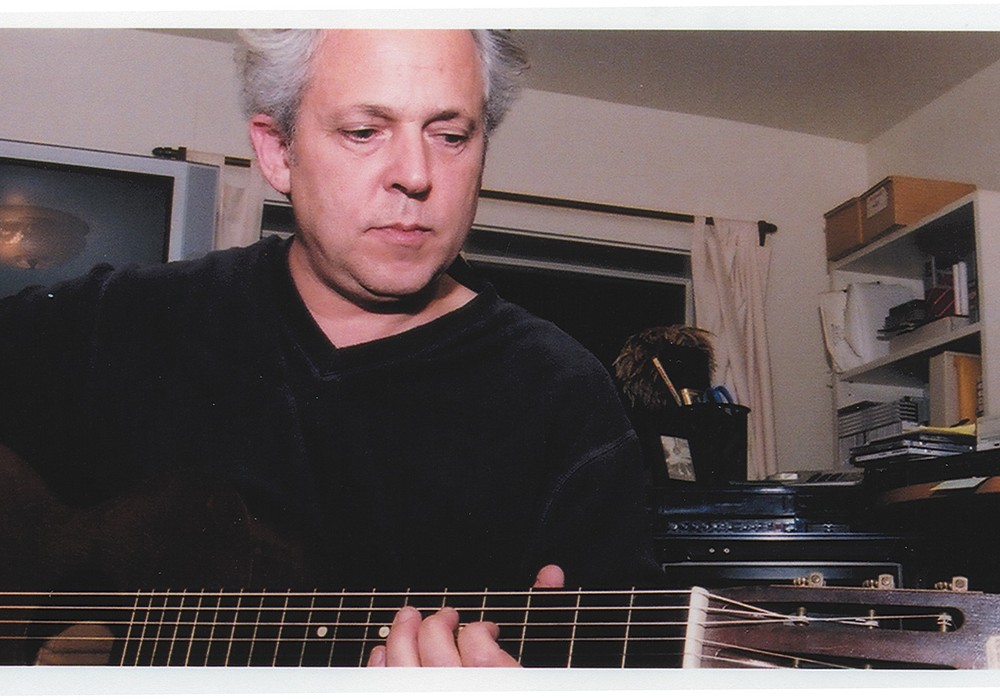

At first glance Columbus, Ohio's Moviola seems like the perfectly conventional band you'd expect from the heart of the Midwest — a couple guitars, a bass, a drum. But as anyone who has heard the band's records will attest, they hover far above the heads of most conventional rock bands. Their recordings are imbued with a post-modern sensibility, both in lyrical bent and sound. When it comes to sound the appropriateness of their name, a piece of machinery akin to a nickelodeon, becomes readily apparent. There are elements both old and new, rock standards and otherworldly nuances. Often labeled 'lo-fi', they've transcended the limitations of their homemade studios through innovative tinkering to create some of the past decade's most immediately engrossing records, namely 1997's Glenn Echo Autoharp and its follow-up, The Durable Dream, both on the Spirit of Orr label out of Boston.

The band — like other Ohio denizens Jim Shepherd, Mike Rep and Guided By Voices — recorded with the equipment available to them, never giving credence to thoughts of what was or wasn't suitable for public consumption.

Spirit of Orr recently released the band's fifth album, Rumors of the Faithful, which reveals the band eclipsing the so-called lo-fi aesthetics that for so long had been an easily identifiable element of its complexion. Not so much a conscious decision as the result of honed recording prowess and advancements in technology — as well as access to better equipment — the tact also highlights the increasing songwriting abilities of the band. While Housh once wrote the lion's share of the band's songs, on Rumors' each member shared songwriting responsibilities equally.

The following interview was done in two sessions: First at the band's former studio/practice space situated in an old mortar factory and where all the band's records were made save for the latest one. Following that initial conversation the band began construction of a new space in Housh's backyard (as the photographs show), as well as began to record what would become Rumors of the Faithful. Housh, who is employed by the Ohio State University as a videographer, was working in an old television studio equipped with a Bellari RP583 tube compressor, AKG C3000, Neumann mics, a Carvin 16-channel board, Alesis monitors and a Tascam 38 8-track reel-to-reel. The band took full advantage of this goldmine, recording the majority of the material for the album over the course of the winter of 2000 and 2001. Only a few overdubs and guest parts from Marcy Mays of Scrawl, Mark Wyatt of bluegrass band One Riot One Ranger (and formerly of Great Plains), and Barry Hensley of Hensley-Sturgis were later recorded in the band's completed backyard studio. This is where part two of the interview took place, after listening to a few tracks near completion. Moviola currently consists of Jake Housh, Ted Hattemer, Jerry Dannemiller, Scotty Tabachnick and Greg Bonnell.

Part I

Why did you initially decide to go to Diamond Mine to record Durable Dream when it seemed, as indicated in interviews I've read, that previously you were pretty adamant about recording yourselves?

Jake: I think we just needed to be reminded how much we still wanted to do it ourselves. We wanted to see how that would go. We didn't like it, which had been our experience other times messing around in big studios. We just don't work that way.

Was it the studio or working with Jeff Graham specifically?

Jake: No, we all like Jeff. Part of the reason we didn't like the big studio, having nothing to do with the equipment or the facility, is that the four of us, when no one else is around, do things in a certain way. It doesn't matter who the other people are — it messes up the dynamic. I'm not saying that was the case there, but usually whomever is there wants to have their input into what's going on and I don't think we deal very well with that. It doesn't matter whether or not it's good input — I'm not making a judgment about that — it's that this has become a pretty tight-knit thing, even on a personal level.

Scotty: Also, the time frame was a big factor. Here we record ourselves and if we don't like something we've done, we can take a step back and get some other stuff done. We can mix it down, take it home and listen, and come back the next day and maybe try using a different instrument. At Diamond Mine we were supposed to be ready to lay down our masterpiece right when we got there. And that made every take more pressure-filled, especially with all the extra people around who want to have a say.

Jake: And for how much it costs to go in a studio you can obtain the tools to do a decent job. We blew a good amount of cash on Diamond Mine and I don't think we'd want to again. I'd rather have an asset. But I don't want to portray Diamond Mine as making it a bad experience for us — it's just not what we do.

Scotty: Jeff is a great guy and he really tried to see what we wanted and to help us achieve our goal. He wasn't doing what he normally does — he was trying to make a Moviola record. It was just more difficult for us to do that there.

How do you feel about the 'Kitchen Waltz Preamble' single (one of only two recordings from the Diamond Mine sessions released)? It sounds a lot different than your other records. It's much more bombast.

Jake: I think it sounds too slick to all of us.

Scotty: It's really jangley and really trebly.

Ted: The guys up in Boston that put our records out really wanted us to put that song out. They really liked it.

So what equipment here did you use on The Durable Dream?

Jake: We used an 8-track cassette machine that only has six tracks that work. We did basic tracks on that. We have this Macintosh [computer] setup, but it's just a stereo in-and-out so you can only do two tracks in and out at the same time. So for most songs, we'd do basic tracks on the 8-track, where we could do several tracks at one time, and then spend some time getting a good mix down to the computer. We did overdubs on the Mac since it's digital and has no tape hiss. So we used a kind of a half-ass, hybrid cassette-Macintosh thing. I don't think that is how we're going to continue to do things though, as it was hard to have everyone gather around a monitor and figure out what's going on. [They haven't — Jake now uses his reel-to-reel in the backyard studio. Similarly, the band records eight tracks, mixes it down on a Mac, then puts it back to one of the 8-track's tracks.]

Ted: It became computer class.

Jake: Or we'd end up waiting for the computer to restart or optimize the hard-drive or whatever — doing other things than recording. Then there were our own limitations. There was a learning curve because we had never done it that way before. We had always just messed around on the cassette, bouncing tracks.

Was that the process on Glenn Echo?

Jake: Even some of that was just 4-track before we got the 8-track. We never did a whole record on just the 8-track cassette. It did wonders for us, though. There were times when one or more of us would come here and work out songs on it. It's been a nice thing. I think we're going to step up, though. I got an 8-track reel-to-reel and we're going to try that, which should be a step up in sound production.

I think there's a definite sound departure from Glenn Echo to Durable Dream. Durable Dream is much cleaner than Glenn Echo. Bela [Koe-Krompecher, owner of Anyway Records] has described Glenn Echo to me as demos. Was there ever any intent to go further with that album?

Jake: There was, but that description is pretty accurate. We spent a lot more time on Durable Dream — thinking about the sequencing of the songs, trying to make it fit together conceptually — and that wasn't the case at all with Glenn Echo. I think it's pretty obvious that Durable Dream wasn't just knocked out or thrown together. I think we thought that Glenn Echo was going to be a 500-copy release and it grew and got to be more than that.

What dictates who plays which instruments? On stage you switch instruments and, judging by the liner notes, you do the same in the studio. How is that determined?

Jake: The recording dictates what we play live. We came pretty close to being able to play the whole record in our set with one line-up. One thing we've never done is do a record and then do anything that makes any sense as far as supporting it. So we thought that this time we'd try to aim for the single line-up. We ended up deciding that we couldn't use one line-up so we started switching around. I've had a lot of fun switching around and playing bass. I think it was getting old using two guitars as well. Scotty got the Rhodes piano and it's been a lot of fun since that happened. It was getting too status quo.

Scotty: We all do different things on different songs. When we recorded, it had a lot to do with 'who wants to play this solo?'

Ted: Or who had a good idea.

Scotty: And we'll even take turns. If someone is on something for 10 minutes and can't figure anything out, somebody else will take over. Jake has been playing piano since he was a kid, but I would still play the part if I wrote it. But there'd be other times when I wrote the guitar solo as well. So we still look at it song-by-song and figure out who wants to play what instrument.

Before going into work with Jeff, was working with Steve Evans on The Year You Were Born the last time you had worked with somebody?

Jake: Yeah, and that came off more like the way we do things.

Ted: We did that record in Jerry's house. Steve came over and we did it on a Friday and a Saturday — 2 days — the majority of it anyway. There were some songs we added later to flesh it out.

Scotty: We gave him a digital delay and a stereo compressor for The Year You Were Born, an agreement we made before we recorded it.

What do you think about being tagged 'lo-fi'?

Jake: We've been lo-fi by necessity. We write okay songs and that still comes through most times. There have been times when we recorded that the limitations inhibited a song coming through, though. I think we stepped away from the lo-fi sound with Durable Dream. Maybe we're not all the way out, but we're on our way out. We're getting to that point where we can do it ourselves and not be categorized as lo-fi. Durable Dream was harder to categorize that way. That's a played-out label anyway.

Yeah, Sebadoh and Pavement are still being labeled that way when they're using sixty some tracks...

Jake: I think anyone who knows anything knows that that in itself isn't an aesthetic. The lo-fi people who have gotten somewhere have gotten there because of the songwriting. The recording wasn't so lo-fi that you couldn't tell the verse, chorus, and bridge.

Ted: We're in a transitional mode right now between supporting The Durable Dream and starting to concentrate all of our efforts on the next thing. Jake is building a studio in his backyard in a barn.

Jake: My folks are tearing down a two-car garage so we're taking all the material we can salvage to build a two-part building where we'll get together. This factory space has no heat. We have a propane heater but we can't leave some of the nicer equipment down here. It won't last.

Scotty: The 8-track will lose another track.

Jake: But we're usually either in playing-out mode or recording mode. Recording goes in spurts because we're not always set up to record here. Ted has a mini-disc recorder and we'll set up a stereo microphone to jot down a song we're working on or to run through the set and listen for errors.

Do you see yourselves taking more time on records? Will you take two years between records at some point?

Jake: I think that's too long, but I can see it happening.

Ted: I think one year is a good time.

Scotty: It used to be that we had to wait for the material. Ted and Jerry were writing one song each, I was writing a couple, and Jake was writing the majority of the record. Now all four of us are writing. We probably have enough material right now for a full-length record. It will be just a matter of recording and getting it done.

Part II

The instruments on the new songs sound more natural than on The Durable Dream. You seem to be letting them sound the way they sound without using effects.

Scotty: That might just be capturing them more accurately technically.

You used the reel-to-reel 8-track? Did you ditch the cassette with the broken tracks?

Jake: That's at Jerry's house. We used it for the demos and there is a very noticeable difference between the cassette and the half-inch format. We also used a compressor and some dynamic microphones.

That's the equipment you were using at the television studio?

Jake: Yeah, the majority of the recording was still done there.

Ted: When you actually get to hear an acoustic guitar sounding really nice, you end up wanting to use it without putting anything on it. If you have a shitty mic hooked up to a cassette, the acoustic guitar won't sound as nice so you're more prone to put some sort of effect on it or not even record that way from the get go because you know it's not going to sound good.

Scotty: We also made a change with the instruments we're using. Jake plays a stand-up bass, which he rented. The stand-up has a more dynamic sound than a regular bass so we ended up leaving other instruments out. Half the songs have that bass sound.

Jake: I think we've always wanted to sound more pure and natural. I like having acoustic guitar in almost every song.

You also brought some new people in to record this time.

Jake: Jerry's really good about the logistics of getting people in. He scheduled someone every week for a month.

You have Barry on pedal steel, Jill [Dannemiller, Jerry's wife] on trumpet, Marcy...

Jake: Mark Wyatt.

Scotty: Laura, my wife, sang on one of Ted's new songs.

So what was the set up like at the TV studio? Were you able to leave your equipment down there?

Jake: Yeah. All the same shit we had at the old studio, but in a room four times the size.

Scotty: It was nice. It had carpet. [laughs]

Jake: It was well heated.

Ted: And the basement was completely sound proof.

Jake: Here, there's all this refrigeration equipment (for the storage of plasma at the nearby donation center), everything we record here has a slight hum in the background. It was an ideal set up at the television studio, but I knew it was going to come to an end. We were there for about six months.

How far along are you at this point? How long till the record is completed?

Jake: We have about four or five more overdubbing sessions.

Scotty: We have all the songs mapped out — we just need to do the final mixes.

Ted: We only had 8 tracks to work with but we wanted a lot more, so we would record all 8 tracks then dump it to Jake's computer and then dump it back to a track, so we've actually already made a lot of the mixing decisions.

Jake: You pull up just two faders and you have the whole band.

How was working on this record different than how you've worked in the past?

Jake: On this record, we've all written several songs.

Jake: That's been unique. Not the democracy of it, but that we've all been writing at the same pace. It's very much a band.

Ted: That's one way it has changed. It hasn't been so much about how we are going to do songs, but how to develop your own songs and have three other people help you do it.

Jake: With each record, we've taken however much time was necessary to do something better than the last one. I think that's been something that changed starting with the recording of Durable Dream — making the commitment to spending enough time to do it. Now we know how to write and play the songs, even though the equipment is different.

Was it hard to leave the mortar factory?

Jake: Not in that we didn't want to freeze our asses off during the winter.

Ted: The old place was just another wrench thrown in the mix of us getting together.

Jake: Yeah, and whether or not someone got propane for the heater. We didn't talk about it that much, but I just thought it was getting to be a pain to go down there. The place is just piled up with crap and we don't even know where everything is. We had to abandon it.

Ted: It was dirty and everything we brought in there got ruined.

Jake: And the TV studio was ripe for taking advantage of it.

Ted: When we got the cassette 8-track, there was nothing wrong with it. It just sat on this table, we never moved it and we even covered it up. The first time we took it in to get serviced, they opened it up and were like, 'Oh my god!' There was so much crap in it.

Scotty: There was pigeon shit in there. [laughs]

Ted: But the warehouse was such a cool place to have and we got it right when we needed it.

Scotty: Jake gave us a deadline tonight for when we have to move all our stuff out of there.

Jake: We haven't used it in forever, but we don't want to give it up.

Ted: It's just getting too expensive and we don't play out that much and hence the band doesn't generate that much money.

Scotty: Except for those bake sales we do twice a month. [laughs]

Are there any other new instruments on the record?

Jake: There's violin on one song. When I turned the bass in, I got a violin. The bass was $50 a month and they let you apply the money towards buying it, but you could only rent it for a year before you had to buy it. Well, the bass cost two grand so after six months I figured out I wasn't going to be able to buy it so I decided to get the violin just so I would have something that I could sell to get back my investment.

Scotty: I think we should trade the violin in on two pocket trumpets. [laughs] Jerry got a cool new instrument.

Lap steel, right?

Scotty: It wasn't on the last record, but we've been using it this time and it has a nice sound.

Jake: We've got it on two songs, and I play some banjo on a few songs.

Do you do much overdubbing of specific parts?

Jake: Most songs are pretty cohesive but in places it's gotten pretty fragmented. The song where I play banjo, we had done the same chord on guitar over and over again for about 24 measures and it didn't work. So I mixed it down on the computer and took that part out and then put in this banjo part. But that's not typical — usually we do it right to begin with. Still there are hardly any songs where we start with all four of us playing. Usually we just record a few things to set up the song and to get some sort of energy between the people. We usually have at least two people. If you do everything single-tracked and build it that way you don't get any dynamics.

Do you think recording over the course of the year for this record is good for your process? Would you ever record in a more intense setting?

Scotty: We've done long weekends where we've recorded four or five songs.

Ted: We did two or three 7"s that way. The majority of The Year You Were Born was done in two days and then the rest on 4-track before and afterwards. The rest of the albums have always taken a while.

Do you ever find that you lose a song taking that much time?

Ted: I think that will occasionally happen to Scott's songs.

Scotty: We're saving ourselves trouble. I think we get rid of the crap because we fight for the good ones

Ted: I don't see why you would want to put yourself in the situation where you have to record in a certain amount of time if you don't have to.

www.moviolamusic.com

Interviews | No. 70

Carpal Tunnel

by Liz Brown, Sarah Murphy

For all of the benefits computers bring to the modern recording studio, wrist health isn't one of them. The repetitive motion typically required to operate music software using a mouse and keyboard...