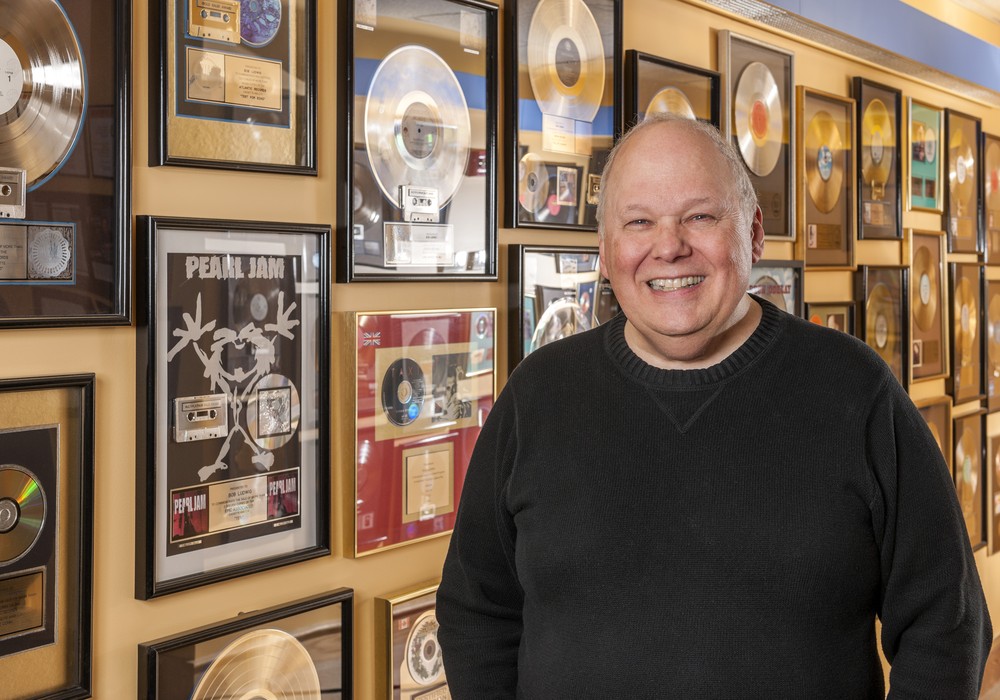

If someone has mastered 8,000 to 9,000 albums to date — many of them rock and pop DNA — they are probably doing something right. Bob Ludwig started cutting lacquers at A&R Recording with producer Phil Ramone [Tape Op #50] in New York. Later on, he worked for Sterling Sound and Masterdisk, eventually founding Gateway Mastering in 1992, in Portland, Maine. His credits include just about anyone you can imagine — Bruce Springsteen, Dire Straits, Lou Reed, Jack White [Tape Op #82], Queen, Metallica, Megadeth, The Band, AC/DC, Radiohead, and Elton John are only a few. Bob was kind enough to tell us about cutting lacquers, early digital times, his approach to a remastering job — as well as the relationship between sound quality and music.

I recently listened to Beck's Sea Change, and it reminded me of how much bottom end a CD can actually incorporate. Some early transferred CDs — or digital recordings, for that matter — are missing low end and front-to-back depth.

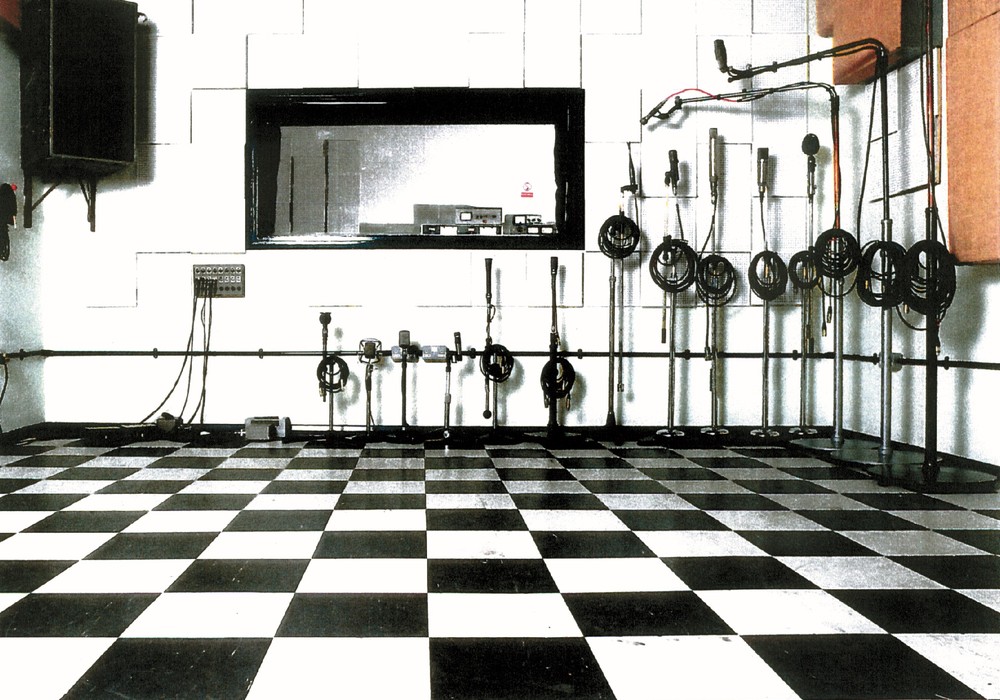

There are a lot of reasons for this. I started working with digital in 1978, when I mastered and cut a recording for Telarc, for vinyl, on the Soundstream digital machine. Until the invention of the Neve DTC-1 digital domain mastering console in 1987, and the Daniel Weiss BW-102, there was no way to master and stay in the digital domain. One always had to play back the digital master through a not-so-great Sony PCM-1610 digital-to-analog converter [DAC], do all the mastering in the analog world, and re-record it back into digital through an even less-good analog-to-digital [ADC] Sony converter for CD — first the Sony PCM-1600, then 1610 and finally the 1630. For a while, as everything was 16-bit — even for post-production and mastering — simple level changes sounded dicey in the digital domain. Digital equalization was initially so horrible and brittle; no one would use it. The PCM-1600 converters were a "ripped from the textbook" industrial design converter that had all those sound qualities you describe. Some great digital recordings, like the Rush's Moving Pictures CD, were recorded with it; but the artists and producers mixed while listening through its output, so they adjusted EQs and levels to accommodate the sound of the converter. The invention of the CD meant that there were now tens of thousands, and then millions, of DACs being sold and all R&D went into developing better DACs. I remember when there were no more than a handful of ADCs in all of New York City! The analog to digital converter took a while for developers to really pay attention to it. In my opinion, it wasn't until the middle 1990's that some really first-rate converters were invented. The first Sony digital editors, which were necessary for creating the CD masters, did not have dither. Even their manual suggested passing through the -60 dB area of the fader as quickly as possible to avoid digital distortion when one had to do a digital fade! The widespread use of dither — which makes low-level digital go from horribly distorted into extremely low distortion, and gives the ability to hear sounds below the least significant bit, was a major leap in the improvement of CD sound.

I read that when transferring some '60s and '70s records to digital for the first time, some engineers kept EQ settings originally meant to accommodate vinyl. Do you think that's part of the problem?

Well, what happened was merely a matter of economics. Mastering engineers had always mastered with the vinyl disk in mind. When they made mastered, equalized tape copies for cassette duplication, it contained all the engineering optimized for vinyl; which means making sure the inner bands had adequate top end to counter the diameter equalization losses inherent in the physics of vinyl disks. Sometimes the very lowest bass frequencies were somewhat "mono-ed" to make the groove easier to cut, and to prevent skipping from the groove thinning out. CDs only sold 800,000 copies total for the USA in 1983, jumping to 5.8 million in 1984, to over 100 million by 1987. CD sales didn't exceed vinyl until 1992. The Dire Straits Brothers in Arms CD I mastered in 1985, one of the very first albums recorded on the Sony 24-track digital machine, was the first CD I mastered that was totally mastered for the CD medium. It was also longer than the vinyl version. That original version had to be mastered in the analog domain, in spite of how great Neil Dorfsman's mixes were. Please re-buy my latest all-digital remastering of it; it's how I always wanted it to be.

Some remasters of old albums shoot for a contemporary "bright and loud" sound. How would a flat transfer benefit today — due to modern converters, playback electronics, etc. — in comparison to the first CD version some 30 years ago?

In the past 30 years, every aspect of the recording chain has dramatically improved. I have...