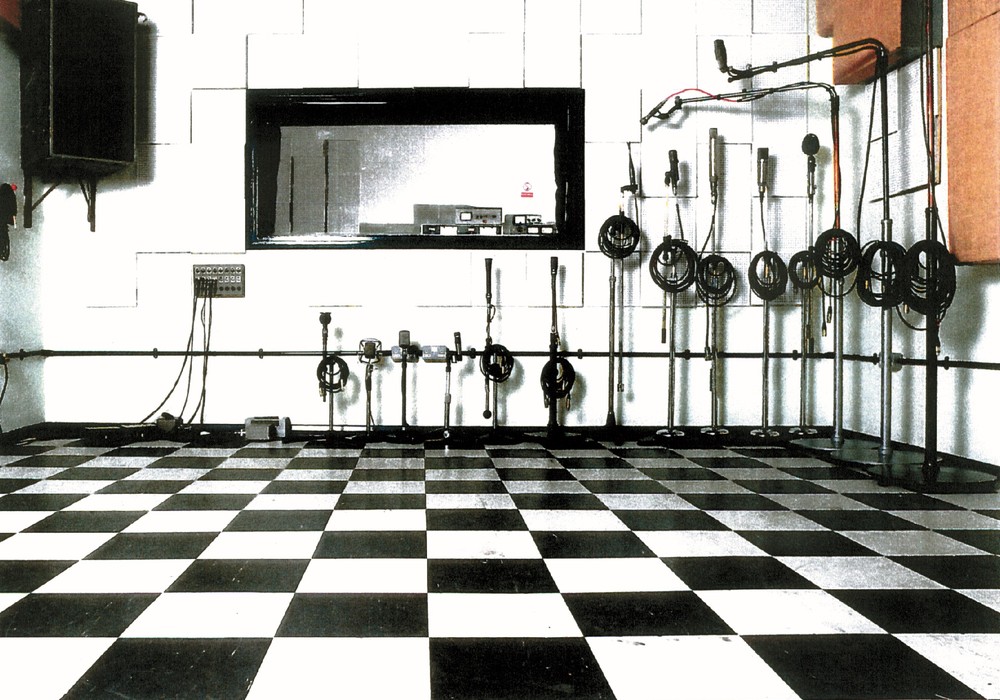

Northward Acoustics is an acoustics engineering and consulting company based in Brussels, Belgium. Its founder, Thomas Jouanjean, developed his Front-To-Back Control Room and Mastering Suite design in the early 2000s, and he now has constructed some of the finest studio rooms all over the world. Clients include Sterling SoundNew York and Nashville, Skrillex, Brad Blackwood's Euphonic Masters (Tape Op #102), Dave Collins Mastering, and many others. I was lucky to chat with Thomas right before my pal, Adam Gonsalves, had him design and oversee construction on a new facility for Telegraph Mastering in Portland, Oregon. The resulting room speaks to Northward's quality, and, having spent many hours there, I can attest that the design works. I'm humbled when I hear mixes I've done in Telegraph, and it's amazing how other work sounds in the new space.

How did you get your start in this business?

First, I had a business school diploma, because my dad wanted me to have a "serious" diploma. Then I went into engineering, because that's what I wanted to do, and I studied acoustics. I knew I would never be a good mix engineer, because I don't have the patience to deal with clients. I knew that this area of audio was what I liked. I decided I would try it for a few years, and I starved for quite a while. Coming out of Brussels, what were my chances? For three years, it was really hard. I would do horrible little rooms with no budget. My parents helped me get fed. But then it picked up; and then it just exploded.

What were some of the breakthrough projects for you?

The breakthrough was coming up with my own technology. When you come out of university you don't want to reinvent the wheel, so you look at what they've been doing. I thought, "If they've been doing that, then it works." I did that for a while, and then I realized I didn't think it worked. It took me a few years, and a few room designs, to realize what the problems were.

In a traditional sense of studio room design, what was not working for you and how were you perceiving it?

I think they encountered the designs by chance, and then tried to justify it. When you look at it in depth, there are some things that just don't add up. I thought there were a few things that either I didn't understand, or there was something wrong. My initial reaction was to say that I misunderstood it, and so I kept doing it. And then I thought, "No, I've got to do something." So, I looked more in depth into it and found, according to my vision of things, there are a few things I didn't understand that felt like flaws. So, I decided, "Why not see what I would do?" My solution is two rooms in one. There's no distortion between the speaker and the engineer, but it doesn't feel strange. That's the bulk of it, and what started everything.

With having a new system in place, was that a hard sell for someone to take the leap of faith and say, "Northward has a new vision on how to build a control room"?

Yeah, it took a few "crazy" people. [laughter] But this is when I started guaranteeing my work, because I knew the system inside and out, and I knew the odds that it wouldn't work were very low. I gave these guarantees; they went for it, and it worked! [laughter]

AG: No studio designer says, "If you design the studio my way, I can tell you in advance how it will measure."

Right, a guaranteed measurement at the end. It shows that mathematically – from foundation to completion – the entire design is tight and checks out. Even people who build great-sounding rooms will not do that.

This is your Front-To-Back [FTB] Control Room and Mastering Suite standard. What would be the basic tenets of construction that guarantee this?

The system is two-fold. I looked at how the room should behave to be problem-free, but also I tied in the subject of how we perceive sound in an entirely different way. In the old Live End, Dead End [LEDE] system, they used the Hass kicker [see sidebar] and other effects to feed environmental info back to the engineer about the space. In a Reflection-Free Zone [RFZ, a more modern version of LEDE] it is a little bit easier, because you have reflective areas in front of the room. RFZs use geometry to create a reflection-free zone around the sweet spot, so they sound a little more natural than the ones that had been deadened, such as old LEDE rooms with an absorptive front of the room. But the RFZ rooms don't really get rid of energy until it is far down in the room, and they'll still feed back something – a diffused version of the Hass kicker – which is basically like introducing distortion in the system. You're adding a variable between the engineer and the speaker, and that variable is related to the direct interaction between the speaker and the room. To me, that's always been, "Why would you want to do that?" Also, that Hass kicker was related to the size of the live room on the other side. That Hass kicker had to be within a certain time frame compared to the time frame of the live room. It made studios incompatible between one another, due to the time frame of the live rooms being different. There were a lot of very blurry areas, and it was running in circles. You justify Paper A with Paper B, and there was not anything I could grab onto; it was just a matter of opinion, at that point. I didn't like that. I decided FTB was a way to still provide environmental feedback to the engineer that did not involve the speakers, or anything related to speaker-to-engineer and speaker-to-room response. The idea is very basic. What is another source of sound in the room that I can use, besides the speakers? It is us. It's the noise we make when we walk, talk, and enter the room. From studies, I knew quite well what HRTF [Head-Related Transfer Function] is; I knew how long it would take for the brain to actually calibrate to a space, what it needs to do that, and what the auditory system would consider a "natural" space.

AG: Not everyone knows what the idea of a head-related transfer function is.

It's basically the influence of the torso, the head, and the pinna – the shape of the ear – on how we perceive sound. So that's the transfer; the influence of all of that on the way we hear. For example, the pinna will give you a lot of information about elevation from the reflection inside your ear. Another aspect is that it's like a fingerprint – everyone has a different set of ears. Part of the auditory system's response is acquired when you're born; it's embedded in your DNA. The other part you are learning as a kid by moving your head around; your brain learns how to identify objects around you from learning what it sounds like when it comes from this direction or that direction.

AG: Why is that important when you're building a room that is semi-anechoic?

Well, our brains and hearing systems don't like to be in anechoic environments. It's very unnatural. What you see is constantly correlated by the brain to what you hear. If you're in a dead, anechoic space, the cues that your brain receives about the space don't match the visual cues. The whole auditory system will distort its steady state response in a way that it will become a lot more sensitive to small reflections, high-frequencies, and anything that can give the brain detail more environmental data about the space. Everything will be enhanced. If you get your brain in that mindset, and then you play music, what you hear is not flat, in the sense that your brain will add a series of filters in between because it's looking for missing environmental information.

AG: It's overcompensating.

Yeah. That's why engineers complain that they add too much reverb or too much delay in dead rooms. Mixes are imbalanced when they move out of the room. The responsibility is not in the room being dead, because the room might measure flat. But we don't measure flat in the space. It's a combination of these two things that makes a room translate.

More how humans listen and perceive the space?

Well, by not having an auditory system not in a "stressed" mode – as in "not its usual steady state." It's in a "flat" (steady state) mode; it's not looking for missing environmental information, it already knows where it is. It doesn't accentuate any of the environmental cues. That's partially what they were doing with LEDE. They wanted that to come, they just did it in a very strange way. For FTB, having the reflective front wall and these two diffusers in the ceiling, the two in the back provides just enough information when you make sound in a room that the brain actually calibrates through these reflections. It's able to say, "Okay, I know where I am. The room makes sense. I'm not stressed by the environment. I have control over what's going on." In FTB terms, these are all called "environmental cues." They feed back environmental information by interacting with "self-noise cues" – the noise we produce in the room.

With a system like yours, how big would you consider the "sweet spot" of listening in the room to be?

That depends on how the speakers are positioned. It's fairly big, the sweet spot. But, you know, as soon as you have a difference of distance between the two speakers, then you have comb filtering. You need to be in the sweet spot. You have some head movement; you can move around. But if the speakers have bad dispersion, then that's no good. The room sounds as good as the speakers do. It doesn't have a "sound."

I know you recommend the ATC monitor speakers. Do you ever have to build a studio with someone else's preferred monitors?

Yeah, but there are a lot of problems with speakers. That's not something I knew when I started; that's something I learned the hard way.

What kinds of problems have you encountered with monitors?

Poorly designed ports. Poorly designed bass extension. High distortion. Just bad drivers, really. Speakers built for price; not built for performance.

And this is not in the cheap range that we're talking about?

Oh, yeah. There are some that we have blacklisted, because once you get into that environment the flaws are in your face. It's not really subtle anymore. If you're in your living room, you wouldn't catch it. But in my rooms, you think, "What is that?" It's port noise, it's high distortion in a low frequency, and it's bad crossover integration. It's been narrowed down over the years, and ATC's are the only brand that's never failed me. It's not something that I initially decided. We built ATC rooms, and people were systematically saying the ATC rooms were the best. Even though technically the rooms were the same; it's only the speaker that changes. I don't force it, I recommend it. But there are some brands that we say, "No, we're not going to work with that."

I know Adam already invested quite a bit in his monitors.

We discussed that earlier. There are pros and cons to both systems. But if I made that choice, I would go in-wall anyway, because that's always better than free-standing. You have more control over everything, and the room is going to be bigger. It's a different way to design. The speaker cavity and the room behave like coupled rooms. But if I have free-standing, it's a single unit. The bass trapping of the front wall becomes very complicated at that point – because I need it reflective – so there's a very complex system of membranes in the front wall that absorb the low end that comes from the back of the speakers, and that eats a lot of space. Down the line I have to respect the choices from the engineer, but the rational decision would be to go for in-wall, because it's always going to be better.

AG: If Thomas is designing a room with freestanding speakers in mind, and he's putting tuned membranes at the exact point behind where the woofer goes, those speakers are in that spot and they can never move or be changed.

If they are soffit mounted, the dispersion is perfect and there's a cavity in the wall. If a speaker ever did need to change, for whatever reason, it would be fine as long as it was soffit mounted again.

When you build a studio, I assume we are talking ground up.

Yes. Usually it's ground up. I don't do upgrades. The problem with upgrades is that usually it's because someone messed up, and then we're called after the fact. We come up, the space is finished, there's no budget left, and usually the answer to the question of, "Can you fix it?" is, "Yes. But how much do you like bad news?" When you have to take down a whole bass trap, or you discover the shell of the studio is badly designed, then it's like having a bad chassis on a sports car. You're just not going to win. That's it. We tend to avoid that because it's a negative way the client can perceive us. We just want the room to perform, but if it's impossible to do the modifications that are needed, then we don't feel like our input is worth the money spent. And usually our advice is, "Go back to your original designer. They should fix it."

How many rooms a year do you think you're taking on, at this point?/p>

Eight to ten. I'm in a bubble. I don't really know how much work the other designers have.

How many people work with you?

In the company, just one. But we have a contractor in Italy that does a lot of build for us, and I have woodworkers in Brussels that do all the decoupling for the speakers. We have an East Coast contractor in New York, and West Coast in L.A. But it's good to work like this because we never know where the next room is going to be. If we had to hire all of these people all of the time, it would be an insane price for the design because we'd have to sustain all that manpower.

It's independent contracting, with trust?

Yeah; really "partners." We trust them, and they know what they need to do. But they do other things when they're not doing studio work, and that's the best way to optimize for everything.

You couldn't have a crew waiting for a job to fly them around the world.

In 2020, that's not possible. I don't know how it was in the '80's. It sounded like it was like that! I think that, to me, that model is dead.

Outside of recording studios and mastering rooms, do you end up doing broadcast rooms or other types of spaces?

Sometimes we do post-production, but mostly locally, because otherwise it would be too expensive. They don't have to be as good as the studios, but we make them that way! [laughter] We tell them it won't be a watered down version. For cost reasons, these tend to be in Belgium, the Netherlands, or France, so we don't have to fly. The budgets are usually lower, though technically they should have more of a budget. We do a few test laboratories as well. We've done a few for Philips. We've done a test room for Focal as well. These are fun projects. We designed an "average living room" for Philips, which was just some basic furniture and treatment so they could reproduce smaller houses or smaller living rooms. They also had an ITU [International Telecommunication Union] and a FTB room built for high-quality testing too. Because they design drivers, and it's all about price optimization, they need to know exactly how their drivers behave.

What gave Northward Acoustics a real reputation, at this point?

That's a good question! As we say in French, "When you're riding a bicycle, you're looking at where you're going." You're not looking right, left, or behind. This is what I have to do. I'm glad I have all this work and I've liked every one of the projects that we've done. There's not one I would say I like better than others. The first project I had in the U.S. was with Brad Blackwood; he was nice to me and gave me a chance to work in the U.S. He's one of the guys that helped me in my career. Dave Collins was amazing to work with as well. We recently worked with Skrillex [NEST Studios] and it's interesting to see how nice the guy is, and how good he is at what he does. He has very sharp ears. But he expresses that in his own way, and you need to learn to read him to see if he's happy with the low end response or if he wants more bass. He's incredibly detailed in what he does. All these people give us something, because they feed back on what we do, and they all have their own way to express their relationship to our work. We take all that information in. But, so far, FTB hasn't changed at all in how it functions. It's evolved in the way it's built, in terms of maybe being more efficient than the first ones were. But the benchmarks haven't changed.

Do you find yourself testing new acoustic products?

Yeah, we're very careful with them. We do the little step method, so each project we might just change 1% of things, or 5%, and see how it measures so we know we can still offer the guarantee. We have so many different measurements of so many different rooms that we can see the deviation. The rooms tend to be of fairly similar size, within a narrow envelope. We haven't done huge, huge rooms or very tiny rooms. We can see the deviations, and we can compare the theory to practice and see if we have a lead as to whether that change created that small difference or not.

Right. And was it better or worse?

And sometimes you can't really measure it; you just feel it, in a way. Like if you push something too far. The only complaint we've ever had was about a quietness in the room. Some people are disturbed by that, and that's something we've learned. There's a proportion of the population that is very sensitive to quietness. They perceive that as pressure in their ears. They mistake that for deadness. They say, "Oh, it's dead in here." "No, it's quiet." But that has its points, because you can work at lower volumes and you can hear a lot more detail. There's a small percentage of people that are affected by that. We've learned to speak with the engineer and ask a few questions that would give us an idea as to whether or not that engineer would be sensitive. In a couple cases we've even had to change the lightbulbs because the filament was audible. We had to go to lower watts, then it was more or less gone.

Outside of designing and spec'ing the rooms, do you have to do quite a bit of continual follow up to make sure construction is correct?

Yes, because we give the guarantee. We'll go visit before the floating floor to make sure everything is correct, because sometimes we have surprises. We need to ensure that the shell is built correctly: the right angles, the right geometry. Then we'll check the membranes. Eventually we'll do measurements at that point, if we have a doubt that they used the actual right thickness for it. Then we'll test it. And you can see it immediately; the deviation is massive. If they use 3 millimeters instead of 4 1/2, it's going to be 20 hertz off. If it's 2 hertz off, it's fine. We do a whole lot of testing at 80% [of the build] before the fabric is on the walls. We'll usually come and install the speakers, tune the decoupling system, test everything, and then test the room. But we first listen to the room with the engineer, and then we'll look at the graph. There's a psychology when you look at the graph first. "Well, maybe I hear that 1 dB bump at 500 Hz." No, you don't; you're just imagining it. We have an extensive listening session. Sometimes it lasts a couple of days. We'll sit down and discuss our favorite tracks, and then we'll listen and test. We've never had to modify a room.

It sounds like you're involved with an incredible amount of traveling.

Yeah, but I kind of like it. I like to meet guys like Adam and talk; it's the fun part of the job. The AutoCAD part is less fun. It's important, but when I have to detail 90 pages of plans, I feel like I'm not moving forward because it's so much detail to process. I'm happy to get on a plane and get my hands a little dirty after that.

I assume the input from engineers and people who are using the spaces is really important.

Even how they use it physically.

AG: Northward makes their own furniture now [Northward Systems].

I make my own furniture now, after talking to these people. We measure rooms without the furniture, and sometimes we measure with the desk in. We see the impact on sound of that and how some desks are fairly poorly designed, in the acoustic sense. We started designing desks for Noisia [Dutch production trio – Nik Roos, Martijn van Sonderen, and Thijs de Vlieger], and I actually found it interesting and a fun thing to do as a side hobby. Then we came up with a mastering desk design and a production desk design, all slotted systems. They are very minimalistic, and they make a big difference, actually. We found a good manufacturer in Italy, and they know how to produce detailed furniture there. We have a partner that takes care of daily management. The next step is to streamline production, which is being done right now, and also get the speaker stands out. They decouple down to 5 hertz.

How?

It's a push-pull system. The push-pull system allows you to compensate for the lack of weight of small speakers. You can always tune it to the optimal setting for that weight.

The actual stand has a system built in?

Yes. It takes a little bit of time to tune it, but once you're done it stays there. It's the push-pull system we use for every in-wall set of speakers. They are in that box and you can see the springs sticking up and down. That is a more refined version of the speaker stand, which can be as performative.

Do you have patents?

No. That's like putting a patent on the wheel. It's all about how you design the system. It's basically springs.

It seems like so much of what you're doing, besides designing, is quality control.

That's exactly what it is. You can't get sloppy. Otherwise you're just designing plans and you're not sure if it's going to work.

Besides the budget requirements that someone might have, what would make you pass on a job?

Conditions are not met for the room to meet benchmarks. If the space is too small, there are a couple pillars in the middle of it, or the structural conditions are not okay.

AG: Thomas's rooms are really heavy.

On average, it's 60 to 70 tons. Once you pour the concrete on the [floated] floor, that's a big part of the weight. You can jump in these rooms and you don't feel like you're floating. You feel like it's hard. Concrete is cheap; just get the load high and everything gets better. You lose the problem of the resonance between the concrete floor and the other floor because the concrete is so thick. Very little bass goes through. There's distortion in non-concrete floors. When the floor is based on wood joists, it creates resonant cavities that deteriorate the room's response. They can bend up and become concave, then the load is not okay. In the case of floating wood floors, the loading on the decoupling interfaces easily and becomes uneven. It's sometimes hard to tell people that they don't have the budget for what they want. For a professional, our rooms are fairly reasonable. If you're a professional and you make a normal income for a mastering engineer, you'll be fine.

AG: The whole point is to get into a situation where you're doing the best work as you can, as fast as you can. It's about refining your workload. Over the life of the room, I'm going to be turning over many projects. This is the point.

You just need to have the work. On average, the rooms are paid for in less than five years. They're usually paid for fast because the engineers get more work done in a day. Sometimes they can raise their rates, but they usually get more work.