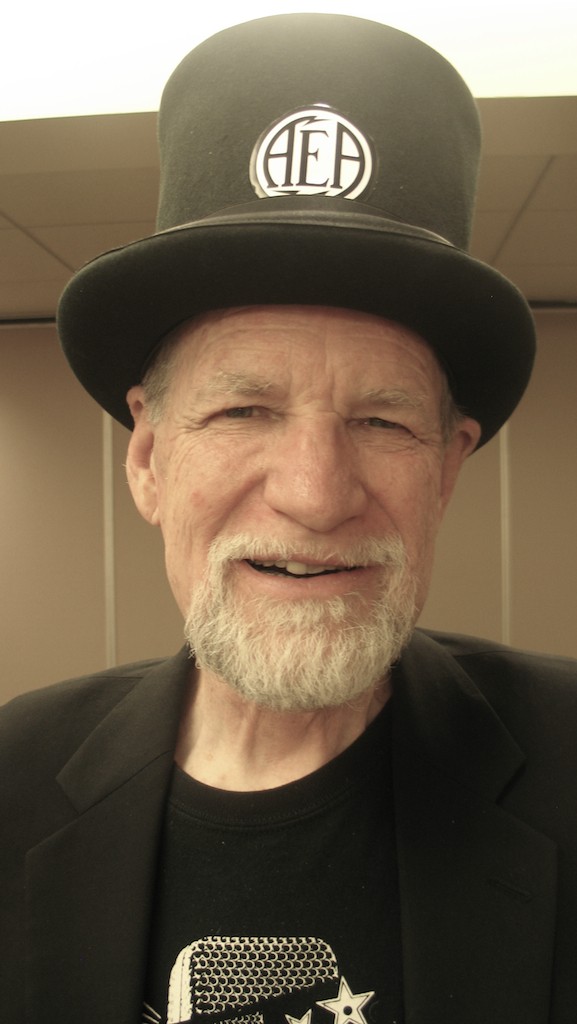

Wes Dooley loves ribbon mics. He's carried the torch for these fine tools for many years, and his AEA Ribbon Mics company manufactures some of the finest microphones of this type, as well as specialized preamps and more. I love listening to Wes spin his stories, so this was a treat!

So, with your whole audio journey, where did you start out?

In high school one of the guys I knew got a Heathkit to put together, in about '60 or so, and I thought that was cool. Then I discovered that since we lived up at 6,000 feet in the mountains, an antenna aimed at L.A. could get all sorts of music. There was stuff that I'd never heard before. Then I had a physics class, and I had to build something for it. I decided to build an audio amplifier, which I knew nothing about. I stole the microphone off the food hall PA and scrounged up a pair of headphones. You could talk into one end and, even if you were talking in a whisper, someone could understand you! The next year I was at Pomona College, and they had a radio station. For a third-class license, all I had to do was sign my name and send it in. All I did was read the transmitter and modulation information. I had a friend who was doing a folk show, so I spun records and he talked about them. I did three years at KSPC FM out in Claremont, California. I got bored with playing the records, so I took their Ampex 350 [tape deck] out of its case and threw it in my car trunk. I talked to The Clancy Brothers, who were playing at the Troubadour that evening, and said, "I do a folk radio show out here. If I showed up at 2 o'clock, would you record something for me?"

Like at soundcheck?

Well, I wanted a radio show. I couldn't imagine anything past the next girl I met, or the next show to do, so I didn't know anything about syndication. I had one roll of tape, and later two rolls of tape, so I did The Clancy Brothers. Tommy Makem was enormously kind. I had this un-cased machine; you could've poked your finger in a number of places and killed yourself. I also had a 664 Electro-Voice [mic]. Our station went dark at 12 a.m., so I just took some key components away and recorded. That was my radio show! Eventually I had my own Ampex 354. Some studio went out of business and I bought a [Neumann] U 47 with a friend of mine. Then we did a trade with an air force base in Germany for a pair of [Neumann] U 67s without power supplies, and we built them. We were making things because we needed to make them. I built a little studio in a four-car garage behind my parent's house. My friend who I started this with, Dr. Robert Gerbracht, had written an article (for an audio magazine) about a preamp he had built. It had a whole mixer section, so you could blend it all. We built some broadcast gear, phono preamps, a mixer for a studio, and a mastering console. I met up with some people who were building some of the first synthesizer studios. I got to meet Bernie Krause and Paul Beaver; I built a couple of studios for some of their first customers. I built Mort Garson's studio; he was mostly a string writer who wrote "Our Day Will Come." I'd met Wally Heider at a remote he did of Jackie DeShannon at the Ice House. I took care of the sound system at the Ice House, Troubadour, and The Ash Grove at one point. I was so impressed with Wally and Frank DeMedio, who was chief engineer at United-Western where they were both working. I got to meet them and help load their truck. I was 22 or 23 by now, and they offered me money to come the next week and help record Johnny Rivers! I had a 1/4-inch, 2-track at this point; the Ampex 354. Wally had a custom-built (by Frank DeMedio) 1/2-inch, 3-track on a Ampex 350 transport. The end result was that I wound up in audio. I paid all of my way through school by recording school and church music in the spring, doing summer festivals, and recording some at Christmastime. I went to school full-time in fall semester.

Work harder...

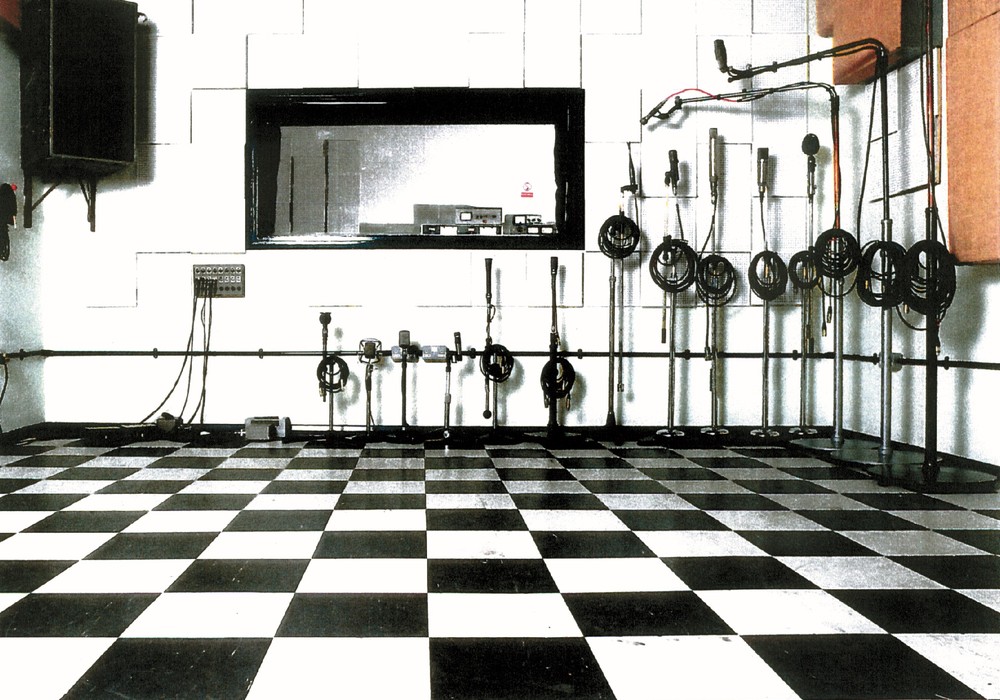

I learned a lot because I would record anything, anywhere. Wally taught me that the job of a really good engineer is to find a good room for the people to make music in, put mics in the right place, and get out of the way. Sometimes you had to be a little bit inventive. I had a very fun time with all of that. I had a portable rig with the Stellavox that I'd put together. I'm incredibly lucky that I've gotten to do really interesting things, and that I spent all those years recording school, church, and club stuff in any environment that there was. These kids paid me money to come down to Calexico or El Centro, and by god, I was going to make a good recording because I was the "Hollywood recording engineer," even if I had to invent the techniques and build my own gear. I started out wanting to be an engineer and work with music, even if I had to have my own gear, teach myself, and find my own musicians. Then, at one point, if you didn't pay me money I wasn't going to listen. At that point I decided, "I'm burned out." I did some other things, like forensic audio and video. I've also built studios for people. I did five rooms for Stevie Wonder. That was kind of fun, as opposed to doing the Philadelphia Orchestra's Mann Center. That was way too much work. I like microphones better.

When did you start seeing ribbon mics around?

In the early '60s, when I first met Wally Heider. Wally would put them up in front of Stan Kenton on the brass and saxophones. I had recorded Stan Kenton at the Reno Jazz Festival and the Redlands Jazz Festival, and he'd always say nice things about my [Neumann] KM 84 or KM 86 recordings. He always hired Wally however. Wally had great ears and would never stop until the group sounded right. When I had a chance to pick up some ribbons, I did. I wasn't quite sure what to do with them, or what to make of them. I tried them on different things. I've tried lots of mics in places where they really don't belong. I have gradually gone from being worried about making mistakes to being worried that I won't be willing to make mistakes.

Ribbon mics pick up the transients of sounds in such a different way than other mics.

Capacitor mics are high-tuned systems. Ribbons are low-tuned systems, and they're totally different animals. If you take a diaphragm and stretch it really tight, like a drumhead, it has resonances that are at high frequencies. When the diaphragms are large, like U 47s or [AKG] 414s, those high-Q resonances (because they are high-Q, just like a drumhead) are in the 8 to 12 kHz range. Those resonances are the reason that it sounds hi-fi. They're also the reason that, if you have someone with a sibilant voice, you immediately start changing things, because otherwise people are not going to be happy with you when they're mixing!

Your mics are not cheap to make.

No. The old-style stuff is quite expensive. The AEA R84, R88 and R92 were done with production costs in mind, but [they have] the same tuning and same transformers as our more costly mics, like the R44, for example. While a 1930's mic, like an RCA 44, actually has some useful output at 30 kHz, they were designed in the days when you wanted a really smooth output to 10 kHz, because that was AM radio. The R84 is only 5 dB down at 20 kHz, and we're not doing any electronic tricks. We work on the assumption that if it sounds really good, you should leave it alone. Our job is to give you the absolute best tool that we can for the widest range of things. Anything that costs close to $1,000 is a whole lot of money! They should be consistent, so in five years if you buy another one they will hold up well as a stereo pair.

I first heard about you when you were selling the Coles 4038s and doing re-ribboning.

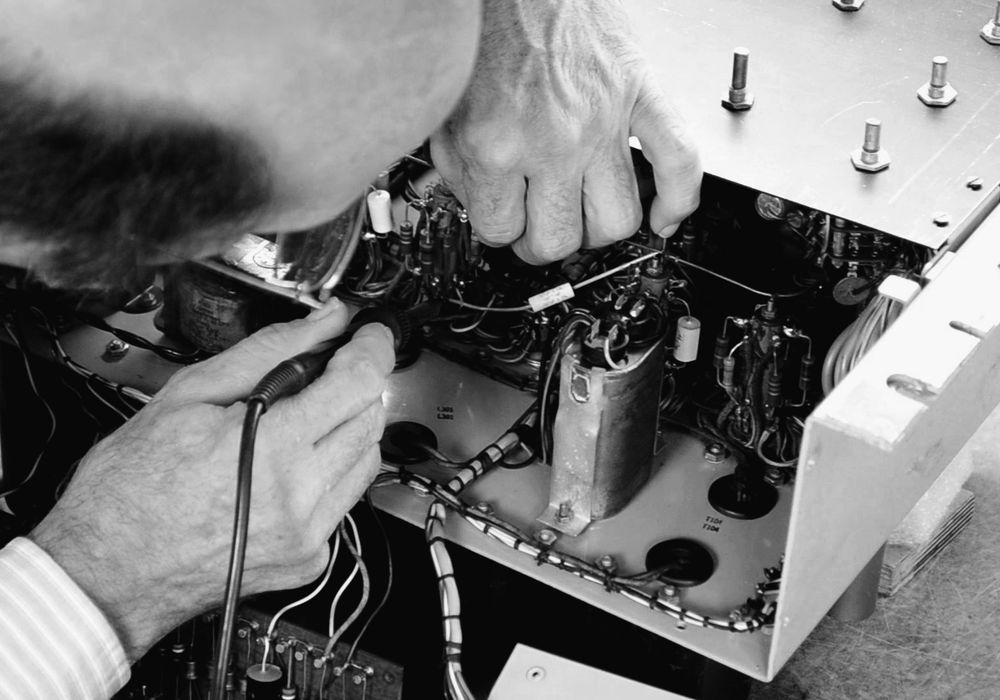

When we started in '76, our chief engineer was friendly with the RCA [ribbon mic] guys. When RCA got out of that department, he said, "Oh, we need to fix those!" He ran our service department. He sent me to meet Jon R. Sank, Stephen Sank's father, after an AES convention in New York. Jon sat me down and showed me how to set up a ribbon on a RCA 44. He sent us the tooling and materials that we needed so that we could do ribbons. In '84 we started importing Coles 4038s and 4104s. For a few years I took them to all the shows. I ran ads and got people like [film sound engineer] Shawn Murphy to use them. I turned a lot of people on to the mics. One day my wife asked, "Do you want to keep doing ribbon mics for a hobby?" I said, "What do you mean? I take them to shows, we do these ads, and we have high profile users." She said, "You've spent three times what you've made." I responded with, "Uh, we'll do a lot less advertising." I kept with it because I liked the mics. About ten years ago I got an award for my contributions to recording technology from the AES. Other people figured out that it was good, but I didn't make any money on it.

What was the first impetus to start manufacturing your own mics?

We had to make our parts for RCA mics. I decided that we had a lot of parts for RCA 44s, which was my favorite mic. I decided to see if I could go with 100 percent spare parts and build my favorite mic. It's an earlier design, before Mike Rettinger's [of RCA Photophone, the Hollywood film sound division] patent for damping screens, which gives you flatter response. The people that we'd talked to when we worked on their mics liked the sound of the un-damped ribbon. This was where I started to understand that it's not about measurement. Unless it sounds good on music, and unless we can make it consistently, there's no point. But we're in the business of doing this, and we have this incredibly difficult tradition of RCA mics to uphold. At the 50th anniversary of the AES in '98 we were showing what we were doing in this direction for the R44. I had a couple of engineers from RCA who came up and said, "We're here for the 50th anniversary, and we heard that you were doing this. We decided to come and tell you that you're ripping off RCA. But what you've done here is so true to the work that we did that this is not even an homage to it — it is the work we did!" I said, "Well, thank you," because people asked if we were going to improve on the RCA mic. I thought we'd be lucky if we could make it sound as good as the original.

I'm amazed when musicians say, "There was that one mic you brought out last time." But they don't know the model name, who makes it, or anything!

But it made them sound like they imagined they wanted to sound. I have been doing workshops for musicians for 30 or 40 years. One of the things I've said all along is that, especially as a vocalist, if you find a mic that presents you the way that you've always wanted to be presented, then you really need to own that mic. Except in a really small, intimate cabaret, you're never going to be heard in any way except through a mic!

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)