Ostensibly all compressors are designed to perform the same function: make the loud parts quieter. (And with makeup gain after compression, the quiet parts become louder.) In its conceptual origin, the idea was simple and practical. The objective was to impart a dynamic consistency to the signal, thereby making it more manageable for recording or broadcast. Compressors are primarily distinguished from one another by the method they use to arrive at this result. So, given the above dull and dry description, how did the compressor come to be the most passionately mythologized tool in the studio?

The language that engineers use to describe their favorite compressors is often florid and rhapsodic, sometimes even hyperbolic. Some people think that the Fairchild 670 is a box of magic fairy dust! So much emotional investment in something that, y'know, kinda just makes the loud parts less loud.

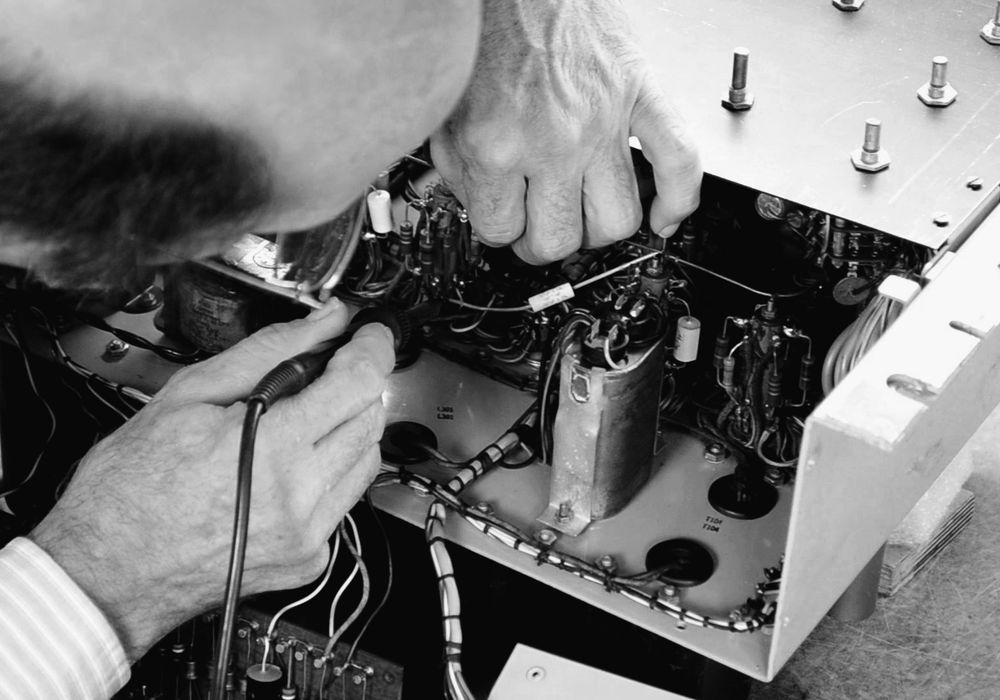

Into this starry-eyed, highly mythologized world, Douglas Fearn enters with the clear-headed sobriety of a master scientist. Laying fairy dust aside, he seeks to create a device that elegantly and efficiently makes the loud parts less loud. He considers many different approaches, carefully studying all of the classic topologies (VCA, photo-optical, Vari-Mu, etc.), but ultimately opts to innovate with a new, tube-based design. The result is the VT-7, a unique tool and perhaps a future studio classic. Somehow the fairy dust got in there too. Which is good. For $4800 MSRP, you want a little fairy dust.

In our studio, we have been living and working with the VT-7 for a number of months now. When it first arrived, we were blown away with its grace and its ability to make any sound "bloom". (There's that rhapsodic, non-scientific language again!) However, we came to discover that developing a truly intuitive rapport with the VT-7 takes time. To some extent, this is because of a unique knob that allows you to dial between a Harder and Softer compression characteristic. The difference between Harder and Softer is difficult to describe. It's not exactly knee or ratio, but some kind of interactive blend of both concepts. It takes a while to get the hang of when to use one or the other, and there is a fluid world in between the two extremes. Add to this the usual attack, release, and gain-makeup knobs, and you have a world of possible ways to shape a signal. Eventually, you develop a musical instinct for how to use the Harder/Softer control, but it's not immediately apparent.

There is also a "secret" setting (unlabeled on serial numbers 25-50 but marked on other units) which introduces a gentle high-pass to the side-chain, thereby attenuating the gain reduction circuit's reaction to low frequencies. This feature is not entirely unique to the VT-7 (the Drawmer 1968 comes to mind), but it is elegantly implemented and exceedingly useful.

The VT-7 was initially advertised, "like having an engineer with infinitely fast hands", which I think is not quite accurate. Sonically, I do not find the VT-7 to be entirely "invisible", and frankly I don't desire it to be. In day-to-day use at our studio, we seek it out for its smooth, euphonic signature. I admit it's possible we are psychologically influenced by the way it looks (the famous D.W. Fearn red!), but we consider it to have a "rosy glow". Subjectively speaking, we definitely find the VT-7 to have a distinct fingerprint.

And let's face it... in the age of the DAW, all of us already do have an engineer with infinitely fast hands! That engineer is called automation. If you give me enough time, I can write fader automation for any recorded signal to micro-manage its dynamics. In mastering work, sometimes this is even worth doing. So, in my opinion, a hardware tool that performs this function alone is merely a timesaver. The VT-7 is so much more than that. In a funny way, Fearn sells the VT-7 short to describe it this way.

When your settings are musically appropriate, the result can be gorgeous and charismatic in a way that is different from anything else out there. Conversely, careless or extreme use can result in the stuffy, unattractive sound that gave compression a bad name. This would not be the fault of the VT-7; wrongly applied compression is wrongly applied compression. I mean, come on, there are very few circumstances where 30 dB gain reduction is a good idea, regardless of what you use to get there, y'know? The grace of the VT-7 is not a license to abuse it. It rewards skill and musicality. If you're one of those people who doesn't trust your own ears-and I believe that this is a very common phenomenon, worthy of a Tape Op article unto itself!-the VT-7 is not for you. If you're an experienced and confident engineer, the VT-7 will feel like driving a really lovely, expensive stick-shift car.

It is worth noting that the VT-7 was born quite late in the D.W. Fearn stable of high-fidelity designs. For many years, the highly regarded Fearn line was limited to preamps, an equalizer, DIs, and the like. The success of these designs lead many to speculate about the conspicuous absence of a compressor. Did Fearn's love of hi-fi perhaps lead him to have contempt for compression itself? In the VT-7, we finally have an answer. It is now apparent that Fearn simply waited until he struck upon a design that met his high standards. Because it does not have an obvious precedent (i.e., it does not directly ape a 670, 33609, 1176, LA-2A, etc.), the VT-7's power is unique and therefore takes a little time to fully master. Such is the nature of innovation. ($4800 MSRP; www.dwfearn.com)

Tape Op is a bi-monthly magazine devoted to the art of record making.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)