Jonathan Little, the man behind Little Labs, is one of my favorite persons on the planet. He is super sweet, has a great sense of humor, hosts awesome BBQs, and he looks and acts the part of a mad scientist. His hair isn't as finger-in-the-electric-socket fuzzy as it used to be; but he's maniacal in his quest to implement what others would consider hairbrained ideas. But his unorthodox ideas actually end up leading to very inventive, extremely useful products-oftentimes things that you can't live without once you try them. And he's actually far less maniacal than he is methodical. He spends years tweaking his designs until they're perfect; and then he offers well-reasoned options so that end users can further tweak the gear to their personal liking. His products have more sagacious engineering behind them than most. The Lmnopre single-channel preamp is a great example. It's like no other preamp; yet its numerous features-many of which are absolutely unique-are so well executed that you wonder how you ever lived without them.

The Lmnopre utilizes a fully-discrete gain stage, offering up to 74 dB of clean but punchy gain. From input to output, the signal remains fully-balanced, delivering considerable dynamic range.

There are two XLR mic jacks-one on the front and one on the back-and you can switch between jacks with the push of a button. This feature makes so much sense. When you feed your preamp through a studio panel or dedicated patchbay, you want a rear-mounted jack. When you track in the control room, you want a front-mounted jack. When you do both regularly, you want both jacks and a method to switch between them! Furthermore, with two selectable jacks, you can A/B two mics quickly. (Unfortunately, phantom power gets switched too; too bad it's not active on both jacks when it's on. But it does ramp gently on and off.) And for audio purists, Jonathan had the forethought to include an internal jumper so that the front jack can be hardwired to the input transformer, bypassing the switch.

Speaking of the input transformer, there's a custom-wound transformer inside, but there are solder points on the circuit board to add a second transformer of your choice, and there's a five-pin connector on the rear panel if you want an easier way to wire in your own transformer. A rear-panel switch selects between the stock and user-installed (or rear-connected) transformer.

There's also a separate, dedicated transformer for the DI, and there are two 1/4" input jacks available on the front. Input A has an active input buffer so it's suitable for passive pickups that need to see a high-impedance load to avoid high-frequency loss. Input B goes straight to the transformer, and it works great with active instruments. But once again, Jonathan gives you internal jumpers, so even these DI jacks are further configurable.

A shallow-slope, high-pass filter (6 dB per octave starting at 120 Hz) relies simply on a polystyrene capacitor that remains in circuit when a high-value capacitor in series with the gain stage is switched out; the coupling cap is unable to pass low frequencies. But what seems like a deceptively plain feature has a bit of mad-scientist twist to it. In concert with this filter, there's LF Res (Low-Frequency Resonance) for adding a

low-frequency "presence" peak. LF Res isn't based on any established EQ topology but instead relies on the aforementioned coupling cap. A knob lets you vary the effect in a complex (and therefore interesting) relationship with gain structure. The size, shape, and frequency of the resonance peak are all affected by both the LF Res knob and the signal level coming out of the gain stage (which I verified using a spectrum analyzer).

In addition to the two knobs for adjusting input levels for low and high-gain modes (Jonathan uses two well-chosen dual-pots instead of one compromised quad-pot to control levels-remember that the Lmnopre has fully-balanced internals), there's an output section with a 1:1 output transformer and an output trim knob. You can bypass the transformer if you don't want its coloration, although if you aren't hitting the output section hard, you won't hear a huge difference in character. Or if you want an abundance of coloration, you can turn up the input gain and/or the LF Res to saturate the transformer, and then use the output trim accordingly. There's even an output trim bypass button, allowing you to use the output trim as a mute or dim feature (i.e. full volume when bypass on and dimmed when bypass off, with the trim knob setting dim-level).

And if all that isn't enough, the Lmnopre also has the phase-align feature first introduced in the Little Labs IBP (Tape Op #33). Two passive, symmetrical all-pass filters are used to adjust the actual phase response of the signal (and not just the polarity-although a polarity switch is also included), with minimal effect on amplitude response. This allows you to "phase align" the Lmnopre's output with the output of another device. For example, if you're using the Lmnopre as a bass DI, you can alter the phase response of its output relative to the output of a recording chain mic'ing the bass cabinet. This can mitigate the destructive effects of comb-filtering when two similar signals are mixed together.

Admittedly, my review up to this point has been mostly a commentary on the Lmnopre's unique features. So I'm sure many of you are wondering how this sucker sounds. Well, to put it succinctly, it can sound clean and transparent, it can sound colored and big, but all-in-all, it sounds fantastic. Let me explain further.

With the gain structure set up for moderate levels without transformer saturation (or with the output transformer bypassed), the sound is clear and neutral but still with great impact-not clinical. Vocals with ribbon mics sound truly expansive through the Lmnopre. Bringing up the input gain and hitting the output transformer harder (and turning down the output trim to prevent overloading of whatever's downstream) adds some lower-mid girth to the sound. It's a subtle effect, but it's easy to dial into an electric guitar part when you need it to gel with the bass. Hitting the output transformer really hard results in a surprising amount of wallop, especially on the attack, as well as some texture on the sustain. You can make a piano bite and growl this way.

Enabling the high-pass filter does a good job of taking out a bit of muddy lows or "chestiness", but it's not the kind of thing you'd use to remove the rumble of a passing train or the "whomp" of a vocal plosive getting past the pop filter. I used the filter once on an acoustic guitar that was sounding too wooly; it worked great, without thinning out the part.

And then there's LF Res. At lower gain settings, LF Res seems to work in broad strokes, and I find it useful for bringing back some of the low end that's lost when a cardioid mic is moved away from the sound source-great for bringing in more drum "body" on a front-of-kit mic, and also useful for that "radio DJ speaking directly into an SM7" sound. When used at higher gain settings, I can "tune" where I want some low-end presence by tweaking the LF Res knob-awesome for accentuating kick drum resonance or tucking a heavy guitar part underneath a lead. And when the output transformer is pushed really hard, LF Res can make things "bloom"-perfect for a room mic on drums or for layering swells of guitar distortion.

Because the phase-alignment section isn't phase-linear (I measured the phase response, and the greatest phase shift is between 200-400 Hz, with the amount of phase shift trailing off above that range, instead of increasing linearly with frequency), it's quite different from delaying (time-shifting) a track. Sometimes I prefer the sound of Lmnopre's "phase-aligned" signal mixed with a second signal, and sometimes I prefer a straightforward delay. For picked bass, I generally favor delay on the DI-the transient of the picked string retains more clarity. On the other hand, for a stereo mic'ed acoustic guitar, the Lmnopre offers a wider palette of sounds.

Experimenting with the Lmnopre is both fun and educational, and a great attribute of this preamp is that you can use most of its features on prerecorded material, abating any commitment to a particular effect while you're recording. Once again a tribute to Jonathan's acuity, the Lmnopre is equipped with balanced inserts between the gain stage and the phase-align section. These inserts not only facilitate adding additional effects while tracking, they also provide the shortest possible signal path to record a clean signal, and you can use the mic preamp and phase-align sections on completely separate signals. Along with the DI inputs, they're also handy when processing tracks already recorded, and much of the examples I give above are with the Lmnopre used just that way, as an outboard processor!

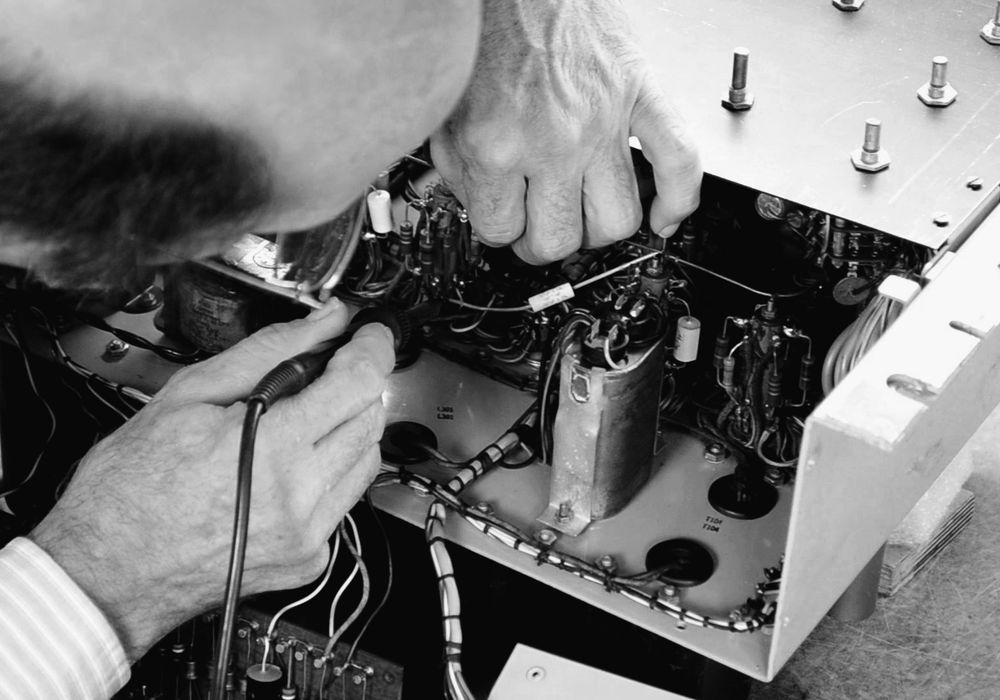

The Lmnopre, like all of Jonathan's products, stands out as being unique in a homogenous market glutted with work-alike, sound-alike, and even reissue-alike gear. But this preamp is not so weird that it's impractical. In fact, it's quite the opposite; once you spend time with the Lmnopre, you wonder why other preamps don't have the same features! Its build quality is top-notch (pop it open to witness details like transistors attached together with thermal compound for precision balancing), and the manual is both informative and entertaining. If you spend some time with the Lmnopre, you'll have a hard time going back to a garden-variety preamp. ($1680 MSRP; www.littlelabs.com)

Tape Op is a bi-monthly magazine devoted to the art of record making.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)