Ted Nugent, REO Speedwagon, Poison, Mötley Crüe, Molly Hatchet, Twisted Sister. When pitching this article to Tape Op, it was not lost on me that many of the artists that Tom Werman signed and/or produced in the '70s, '80s, and early '90s are probably exactly what drove a good number of this magazine's readers to create a scene, as well as methods of making and recording music, that circumvented the commercial rock establishment. But I probably wasn't the only kid running around the streets in 1987 with a Maxell XLII in his Walkman that had Poison's Open Up and Say... Ahh! on one side of the tape and Hüsker Dü's Flip Your Wig on the other.

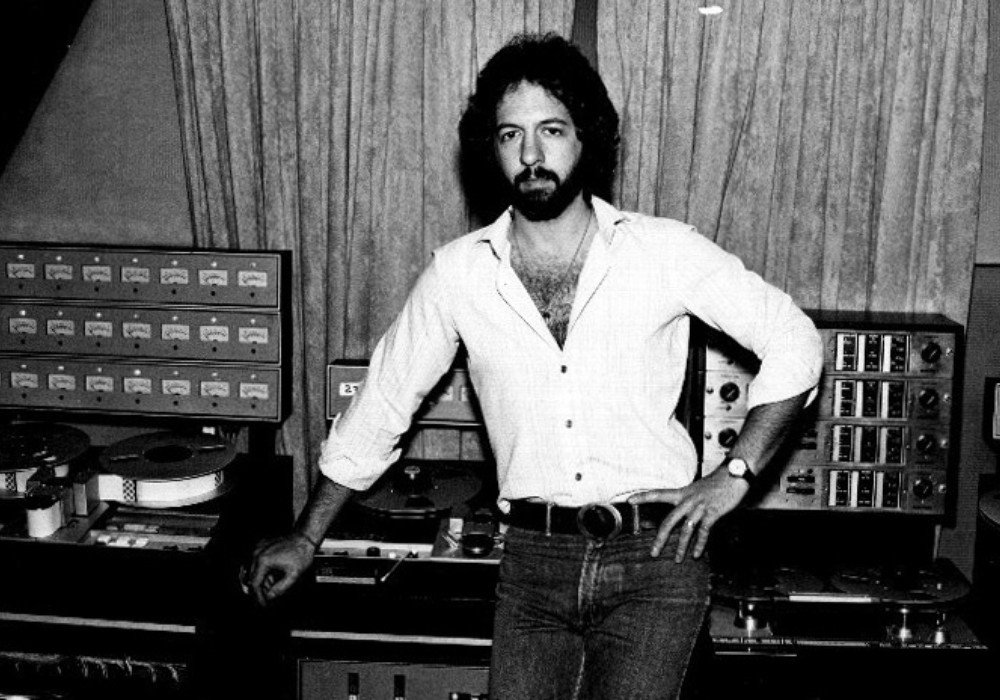

Even if I was, it's hard to argue that Cheap Trick's late '70s trifecta of In Color, Heaven Tonight, and Dream Police — all Werman productions — weren't the high water mark of American power pop. Werman, now 69, stopped making records almost completely in the mid '90s when the alternative rock revolution resulted in him becoming essentially unemployable, due to his close association with glam metal. He says, "I was already 55 in 1990; time to hang it up, really. How many lifetime producers work successfully beyond that? A handful. Tom Dowd, Jerry Wexler, George Martin, and Phil Ramone. Not hard rock guys though." Rather than slog it out, Werman opened a luxury bed and breakfast called Stonover Farm, located in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts. The establishment is still thriving, and that's where I visited him on a snowy winter's day to discuss his unusual career arc, unwaveringly pop aesthetic, and, most importantly, what it was like to make hit records in an era where the budgets were even bigger than the snare reverbs.

You did not come up through the studio system. Instead you got an MBA from Columbia University. Did that degree, or anything in your business training, help you later when you were making records?

The degree basically helped me get a job. I had a concentration in marketing, and I did it mainly to stay out of the Vietnam War, as well as to please my parents. I went into advertising — major league advertising — and I hated it. Music was always the main thing in my life. I just couldn't ignore it, and I knew that I had the capability for it in some way. I wrote a letter to Clive Davis; the fact that I had an MBA made me appear more serious. I presented myself as a musician who was a student of rock 'n' roll, who also had two degrees and a job. Instead of saying, "Give me a job. I need a job." I said, "I'd much rather work in music because, honestly, I don't like what I'm doing." I think I saw three or four other people and the last one said, "I want you to see Mr. Davis." Mr. Davis gave me a job and that was it.

When you were at Epic Records, one of your responsibilities was editing songs down to single length. Was the actual edit that you did the one that ended up on the radio, or did you do an example and then somebody else would recut it?

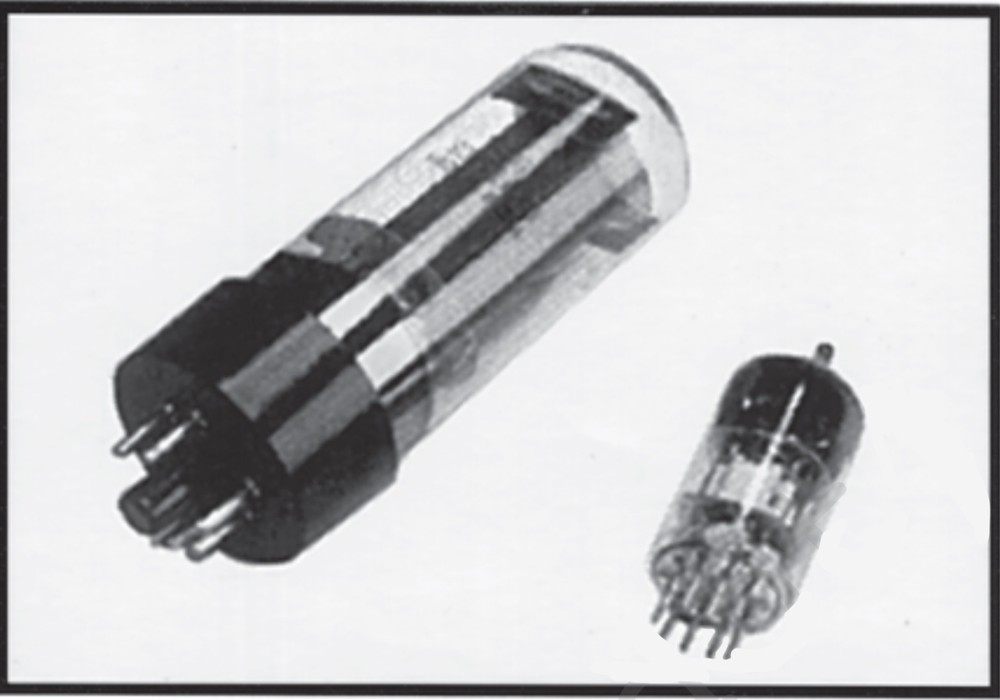

I had a tape machine and a splicing block in my office. I really enjoyed editing. They'd bring it to me and they'd say, "How do we do this? How do we get this 8 minute song down to 3:20 without butchering it?" I'd figure out a way. I'd just listen to it a few times. I had the pop structure in mind — intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, solo, verse, chorus, out. I'd make notes. You had to make sure everything was the same going into the splice, and out of the splice. I got very good at hearing whether it would work or not. I wasn't allowed to touch the master. We were a union shop at CBS. So, I'd take the model from my office, walk it down to the studio, and give it to the mastering engineer. I'd say, "Edit here; 1, 2, 3, bang," and he'd copy it exactly. I did some songs that had seven or eight cuts in them. The O'Jay's "For the Love of Money" was so long [7:14]. It was great because it was wide open — it had a lot of space in it. Anything from Philadelphia wasn't going to have much of a tempo problem.

The first artist you signed to Epic was Ted Nugent.

I didn't know what a producer did when I started; I was a talent scout. Embarrassingly enough, I signed Ted Nugent. That's really hard to explain to people these days, given his views and outspokenness. But actually, he's a really good guy. He just got twisted at some point. Ted had a production deal with this guy, Lew Futterman, who would call the shots. He could be the producer. I was kind of bummed by this because I was thinking that maybe I would get a producer. I actually asked Pete Townshend's lawyer if he would consider producing Ted Nugent, one day when we were on a plane together. She laughed. But, to her credit, later on she sent me a letter congratulating me on the success of the record. I horned in. I went into the studio a lot. I slowly, but surely, started making suggestions. Lew was a reasonably creative guy, but he didn't know much about rock 'n' roll and he was nice enough to give me co-production credit. There I was — a producer. I also remixed the whole record. He mixed it; it was delivered and I didn't like it, so I asked for $5,000 to remix. I took it back down to Atlanta, where we had made it, and I mixed it with a really great engineer named Tony Reale. Unfortunately later he borrowed some...

_display_horizontal.jpg)