Producer/engineer/songwriter Ben Hillier's work ranges from indie guitar bands to synth-driven music. He's produced the last three Depeche Mode records, singer/songwriter Nadine Shah, Blur's Think Tank, Elbow's Cast of Thousands, Graham Coxon, Doves, and The Futureheads.

Elbow's second album, Cast of Thousands, contains "Grace Under Pressure," a song with a stadium choir at the end. How do you get a crowd to pull this off?

After their first album [Asleep in the Back], they got booked to play Glastonbury. At the concert, Guy Garvey, their lead singer, decided out of nowhere to say, "Glastonbury, do you wanna be on our next album?" Off the top of his head, he made up a phrase for them to sing and got the drummer to do a click track. They all sang it, and so they had a recording of that and we sampled it. The band ended up writing a song around that sample.

Did you have problems with pitch and timing?

With a crowd that big, the pitch is so vague, so it isn't much of an issue. We did have to pitch it a bit, but they had been working with the sample when they wrote the song. I think Guy had played the chord before, so he had sung the line to the crowd in a key. And they were pretty close! It was more of an issue with the timing, which was pretty vague. When we made the album, the first thing to do was to get this section down. One of the concepts of the album was that everybody who had anything to do with the record, and anybody who came to visit them, had to sing on that section. So it was the Glastonbury crowd, plus 50 or 60 other people on top. We had that track record to go all the time.

What strikes me about the Elbow records are the guitar sounds, with their slight lo-fi edge.

The way they lay out their frequencies is quite good. The drummer is fantastic, and his tone is great, so you can get quite a big sound on the drums. The bass tends to play very low; there's not a lot of top-end. The guitarist's melodies are quite good at standing out on their own. You can make the guitar sound quite small and hard. And I got it to poke out quite a lot, because I wasn't relying on the electric guitar to set up the warmth of the track. It is usually the bass and the keyboards that are doing that. Listening to it on its own, it is quite aggressive; all the other frequencies are covered by the rest of the band on the track. Guy's vocal is also quite low-pitched and warm sounding as well. There's quite a lot of space in the guitar register, around 1.5 to 2 kHz, you can poke out really well. Craig Potter, the keyboard player, was very good at choosing his sounds. Quite often, keyboards are tricky in rock bands. They're difficult to blend in...

Since they can cover a broad range, from top to bottom?

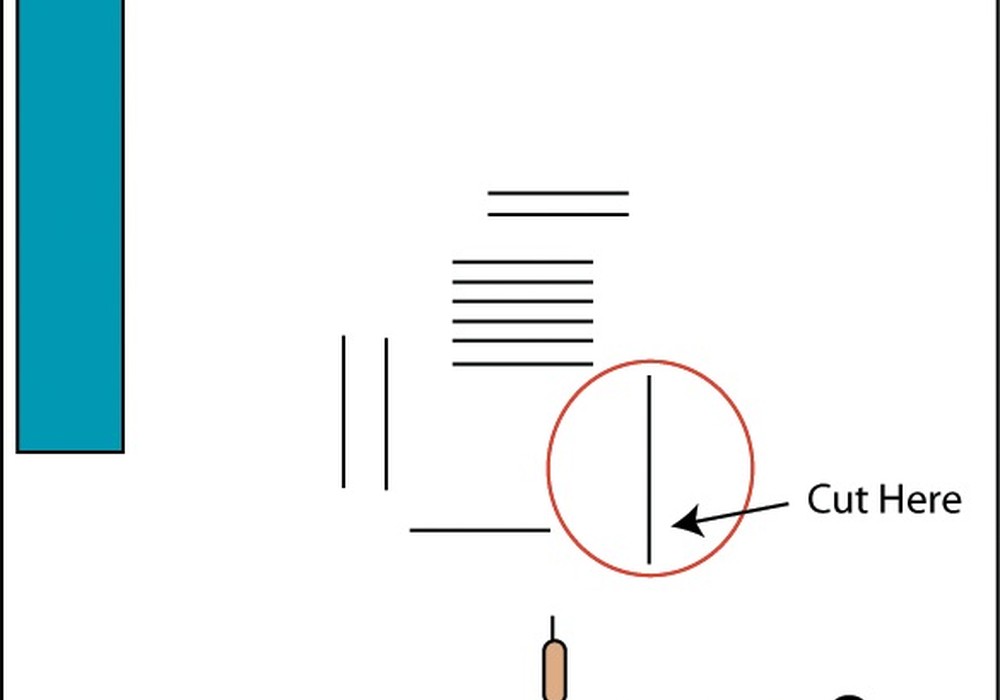

Exactly. Normally the keyboards are trying to do everything. Craig is quite good at being minimal and keeping a sense of space in sound. As soon as you get those types of players and sounds, the rest is quite easy to sort out. A lot of the guitar sounds were recorded with a ribbon microphone 15-meters away from the amp! We worked in a large studio [Parr Street] in Liverpool, and the room was dry enough not to color the sound too much. But when you put that in the mix, it sits in there really nicely. I nearly always record a guitar amp with an [Shure] SM 57 on it, but that would be purely as a spot mic; it will be the focus of the sound. The "character" sound will be something presumably a long way away from it. I'm recording guitars with a lot of space on them. If the room's right, I can do 10- to 15-meters away. The close mic will give it the definition, but the sound will be the room mics. My studio, at the moment [The Pool in London], is in a great big open warehouse space. We have a couple of room mics at the ceiling, which is about 10 meters high. It's not very "wet" though!

Sounds a bit like Abbey Road's Studio 2, which is a big room, but it doesn't have a large reverb tail either...

Exactly! And it's great when you record in such rooms, because you can get the distance from the mics, but you get a much less "bent" and colored sound as you would in a really wet-sounding room. Right up close to the speaker sounds a bit choked to me. It always sounds to me like the sound doesn't have space to move in the air. Guitar amps aren't designed to be listened to at a really close distance. They are designed to be listened to from a distance, so I record them like that.

If you record them right off the speaker, you're always trying to make up for the sound. You're trying to mimic what you hear in the room...

Exactly. And if you can get that result without having to resort to compression and reverb, it will be a much more natural sound. Adding reverb will add mud and messiness, which you don't get acoustically in the room. It's very difficult in the modern age, since most people record in very small spaces and not in studios.

Early reflections can be troublesome. Someone recently claimed that you actually get the best "small room" sounds in dry-sounding big rooms.

Yes! The great thing about big rooms is that the walls are quite far away! If you want to have a sound that is less colored, you just keep the microphones away from the walls. The sound is really clear and direct, even though the microphones are quite far away.

I heard you have a collection of old synthesizers that you use a lot on your productions.

My three main ones, at that time, were the Korg MS-20, ARP 2600, and an EMS VCS 3. When I started out as an engineer I had to justify the purchase, so I used them an awful lot for treating sounds, especially for controlling the frequency range by using the filters of the MS-20. You can take sounds that would take too much space in a mix, tune them into essential parts, and give them a lot more character. The thing I like about it is that there are no presets. You don't step through and ask yourself, "Is that one good, or this one?" Going through presets is the most boring thing you could possibly do in the studio. Instead, you can go in there, build the sound, and patch things through the way you want them to be. I find that much more creative. That's a problem with software synths to me: It will only let you change the sound so far, but won't actually let you get in there and mess around with it. And just by their nature, you're removing what makes the original analogue version great — the unpredictability and the constant variation. Digital can't do that. Digital is a victim of its own success. It has become so easy, and what companies want is to sell plug-ins to people who can't afford going to studios. That's where they're gonna make the most money. People who are developing and experimenting in studios, that's not their target group. If you can afford going to a real studios, you're going to use a real [Urie] 1176 compressor.

The last Blur album, Think Tank, took 18 months. You built a studio in Marrakesh, Morocco, and hauled a big console along. From a producer's point of view, it must have been a difficult record since guitar player Graham Coxon had quit?

Yeah, [it was] difficult, in some ways, because we didn't have Graham. He's an amazing musician. I've done four solo records with him. He has a very strong musical DNA. Obviously that was a real drawback: you've got this band and you're missing one of the main parts. The gap Graham had left almost served as an inspiration to the rest of the band, especially to singer Damon Albarn. Making a record without Graham was like starting again. It was their seventh album, and at that point as a band, there's not much you haven't done before.

Who came up with the idea to record in Marrakesh?

Damon had been to a festival over there, and he loved the fact that there's so much live music everywhere. You'd walk into a carpet shop and they had a band playing, rather than the radio on. There are live musicians everywhere. It was less than a year after 9/11, and going to a Muslim country everybody told us to be careful, but everyone was really lovely and we were never threatened or anything. We were never worried, at all.

How did you get the gear to build a studio?

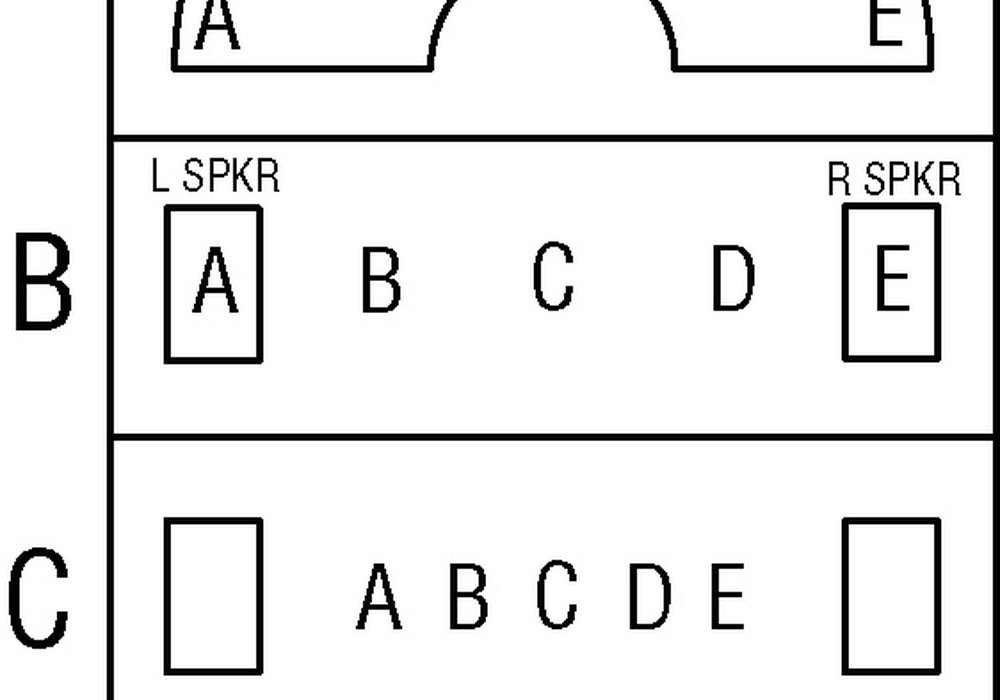

We rented the equipment from Tickle Music Hire in London. They built the studio. It had Genelec monitoring and a Rupert Neve Amek console — a good sounding desk. Lots of outboard, mic preamps, API gear, and Urei compressors. I think it was the first time I did a record entirely on Pro Tools reliably. We mixed to 1/2-inch tape, but recorded to Pro Tools. That gave us a lot more freedom to move around, since we didn't have to work on a multitrack tape machine with heat and weather issues. We brought the whole studio back to England to finish it off. So we'd been in Marrakesh at 40 degrees [centigrade], next to the desert, and we came back to Britain and we went to Devon. It's possibly the wettest place in Britain, in autumn. Windy and wet!

Why did you mix in Marrakesh? Did you want to finish the project right away?

Yes, that was my aim. Damon is a really fast creator. He's interested in the spark of creativity, and making something new is what excites him in music. If you put Damon in a studio, he'll write or start a song. But to finish a song is hard work, because that's boring. Finishing a song, you have to knuckle down — getting the vocals and the lyrics right. With the early version of the song, everything is almost there, but it's just not finished.

At that part of the process, you're becoming more of a craftsman instead of an artist.

Exactly. You're crafting it in the end, which is a real discipline. The reason we went to Marrakesh was that there were a lot of distracting things in London. They were very famous at the time, and it would've been easy for somebody to come in and take them off partying somewhere else. They were pretty disciplined when we were in the studio; but it was increasingly hard to focus everyone, so we went somewhere else. They didn't have anything else to do; there were no distractions. And it was a question of forcing Damon to finish off things. So in Marrakesh, Damon and I really knuckled down the songs.

You were basically trying to capture the moment of creation?

Exactly. With some artists it's the hardest thing getting to finish records. To finish a song, without losing what excited you about it. In all my productions, I will keep tracking as open as I can, for as long as I can. I never understood the overdubbing productions, where the band writes songs, then you bring the drummer in, and afterwards you do all the bass tracks. To me, there's no excitement and no spark. It's not even craftsmanship; it's just drudgery and going through the motions. The thing that excites me is when everyone starts playing and something comes out that excites everyone at that moment. You have to make sure not to lose that, and also to remember very clearly what their inspiration was, as well as what excited you about it. Then you have to be very delicate to make sure you can bring that out and don't swamp or drown it. That happens very easily! The temptation with computers is to record something, and then put it in time afterwards or tune it. That's not what excites me. It's very much production by numbers, putting things in time and tune. That's a last resort to me. I have to be forced to do that.

Sometimes, the actual sound of an instrument sparks an idea. When you get to it later on, with a different sound, the spark is gone.

Yeah, that's very true. Strangely, once you've completed the song and you've managed to maintain the thing that was great about it, it's much more robust. Then you can learn what it is about it that is great. But until it's a complete thing, it's a very delicate flame, and you have to be really careful to look after it. It's easy to undermine. Because of that, I tend to work very fast. As soon as we're excited about something we record, build it up, and focus what we love about it. We don't worry about technical details, because that can all be sorted out later. We have a level of technical attainment we can rely on, which means anything we record will be useable and feasible. Unless something breaks, or a connection is faulty, just keep going!

You're a songwriter, as well — how important is that perspective for producing records?

I think it's important to be musical, and to understand how to put a song together. Writing a song is quite a different job that has nothing to do with producing. I'm not in production mode when I write a song. Trying to produce a song while you're writing it can be very destructive. You can easily spend a lot of time overthinking subtleties that shouldn't be subtleties yet. You have to reject that part, see what happens, and then cut things. The Nadine Shah album [Love Your Dum and Mad], I co-wrote with her and it took a lot of time to write. Then we had to go away from it and work out what the project was — what worked and what didn't work. If I'd been in production mode, I would've made those decisions earlier, but I would have probably gotten them wrong at that stage!

When you got the call from Depeche Mode to produce Playing the Angel, were you surprised they chose you?

I was surprised. I hadn't done any synth-heavy records. I knew [Mute label boss] Daniel Miller. I had worked with him before, and he knew I was into synths. I'd done much rockier stuff before. I think the key element was that, as a producer, I'd basically always done live drum kits. Obviously Depeche Mode have very little live drums on their albums. But, as an engineer, I'd done an awful lot of program music, doing dance music for years, and Daniel Miller knew this.

What did they expect from you?

Basically they said, "We have these songs. Do you think we could make a good album out of them?" And there were some very good songs, so it was easy. There were certain challenges involved with working with them for the first time, and them being such an established band. But they were very easy to get on with. And Dave [Gahan] was beginning to write — he'd written an awful lot of songs, and he didn't necessarily know which ones were suitable for the record. He gave me 15 to 16 songs and said, "You and Martin [Gore] choose which ones fit the album. Pick what you like." That was very brave of him! It really helped Martin and I form a good relationship. Some of Martin's songs were finished already, like "Precious." As far as I was concerned, the demo was great. The drums weren't, so we spent quite a lot of work on the drums, and we knuckled the vocals down. But sonically, the demo was really good. There were a lot of elements I wouldn't have used — [such as the] quite modern Nord Lead synth, and an [Access] Virus virtual synth. He tweaked the sounds and programmed them. I said, "We don't need to change that; it's not broken. We need to get the grooves right, and we need to get the vocals right to fit in the right spaces." A track like "Precious" is quite hard to sing, because it isn't full on. It has to have a subtlety to it to make the lyrics work. We worked with Dave to get that right, and Dave is great at that.

The song deals with divorce and feeling guilty for a child — it has a fragile element to it.

Absolutely. That was very important. That was the key to the song. Making sure it didn't become too strident — to stay quite personal instead. It needed to have a gentleness. With a song like "Precious" that was the aim; making it a band song rather than just a Martin song. The songs that Dave had written, that we really liked, were quite a long way, stylistically. So it was a question of reworking those songs and trying to improve them. Make the bits of them that we really liked be the bits that really shone out.

How did you establish trust for working on their songs?

Martin is quite precious about his songs, or at least he was at that stage with me, because we didn't know each other yet. He used to be quite defensive about his songs, whereas Dave's songs he hadn't written. Dave was precious about his songs, too, so we had to make sure he was happy with our results. That was a really good exercise. It meant that later down the line, there was trust established to work in writing together. Martin had a tendency to never give you songs that weren't finished. As a producer, this is a strange position to be in because there's not that much room for maneuver. You don't want to fully dismantle the songs because, as we talked about earlier, you might lose what's great about it. On the other hand, being in on the creation of the song can be much more exciting — so you get a really special version of the song recorded.

You might create something bigger than the writer might have achieved alone?

Exactly. And that was the difficulty with Martin. The only song that he really let me do that with was "John the Revelator," because he wrote it in the studio. He worked at the guitar part and had the idea in his head for the song. He played it to me. I went, "Great. Let's do that now" and off we went. I kind of took him by surprise. [laughs] He was expecting me to say, "Go do the demo, and then we'll do it!"

He couldn't protect the idea any longer...

Exactly! [laughs] He let it out! That worked out really well. On the next album, Sounds of the Universe, we did a few songs like that. The song "Wrong" was very different from the demo. It was great having that growing relationship with him. We reached a point on the last album [Delta Machine], where there was full trust. [laughs] It is a very intimate thing to work on a song with somebody. When you write songs with people, it is very hit or miss as to whether or not the relationship will work. Friends of mine are great songwriters, and we say we'd love to write together, but it doesn't work, even though we get on very well.

When Depeche Mode keyboardist and sound designer Alan Wilder quit in the mid '90s, they lost the guy who'd built their sonic landscapes. So now, basically every producer becomes a member of the band for this period. Did you create a sonic vision for Playing the Angel?

It was a bit of a reaction to the record they had done before. Exciter was very much in the programmed world, and very electronic. Everything was very specific, whereas I wanted to be getting something that wasn't so digitally nipped and tucked — something that had a bit more of a rocky, bluesy element to it. I wanted the excitement of a performance. Very often, we'd record live performances of synths instead of programming them. Or we'd use lots of different sequencers and older drum machines, because I didn't want it to sound like the software sequencer that we'd used. Say I was programming in Logic, for instance. Pretty much everything I'd program in Logic has the same feel, because the functioning in Logic pushes me in a direction. I wanted the opposite — music programmed on an Akai MPC drum machine, an ARP Sequencer, or something like that. I wanted to do it as I would with a band, where I'd have a drummer with a certain feel, and a bass player [that I] would work in a certain way with him. We've done that with all three records, but we changed ways of doing it. I wanted it to be a messier, bigger-sounding, more open record.

Their Sounds of the Universe DVD shows some studio performances. I noticed what great performers Dave Gahan and Martin Gore actually are.

They are fantastic performers! Dave as a singer, and Martin is an amazing musician. He's got great feel. You could spend ages programming the sound, and it wouldn't be right. Martin would play it, and it would be right straightaway! [laughs] At the time, we were doing Playing the Angel, I think they were at quite a low point. Dave was clean and Martin wasn't. It really felt like they weren't sure whether or not they were going to do any more records after that. Martin was kind of giving it his last go. A lot of the record involved getting through that. On the following tour, Martin gave up drinking, and he was a much happier chap. Now Martin and Dave are great friends again; probably better friends than they've ever been. Being a very successful rock musician creates a very strange setup of pressure. I think they're comfortable now, and they were very graceful in the way they handle it. I think that it takes a while to learn that. Any band who, from a young age, has been told by lots of people that they are great is a recipe for disaster! [laughs] If you're growing up and everyone out there says you're brilliant, it does funny things to your head. There were points on that record where I really didn't know if they were all going to stay in the same room. But they did! They chose to be professional about it when they needed to be, which is exactly the right thing to do. My approach to these things is to make it clear, "Look, we're here to do a job. We want to do a job, and so should you." All the other crap is exactly that — crap. It's got nothing to do with making records. I tend to be very compartmentalized, in that way. "We are working on this record, and we're making this record. Other things are of no consequence."

Maybe they needed someone pointing this out?

Exactly, rather than to get involved in any band politics, which, through experience, I know is a stupid thing to do. They've known each other since they were kids; they went to school together. It's like getting involved in family politics when you're not in the family. You don't know the depth of the feelings and how things run.

On Playing the Angel some vocal tracks were distorted.

For some tracks we wanted a real drive. As he's getting older, Dave's voice is getting a deeper growl to it, which wasn't there on the earlier albums. That responded really well to distortion. Dave's got a great rhythm in his delivery, and we were emphasizing that; making the songs heavier and the sounds darker. It was a question of making his voice step up to that. A bit of drive and distortion really did that, as we did with the drum and bass sounds.

Distortion on vocals is a double-edged sword. It gets more aggressive, but it also thins the sound out so the vocal delivery loses impact and depth.

Yes, you have to be very sensitive as to how you do it. I never use just the purely distorted vocal. I'll always have the dry track blended in as well, which usually gives me the definition, the clarity, and the size of it.

What was the vocal chain on Delta Machine?

On Dave we mainly used a [Shure] SM7 with a LaChapell 992 mic pre, with either a Retro 176 or a [Urei] LA-3 compressor. He usually held the mic so he could perform in front of the speakers. He'd quite often use open back headphones, as well as speakers. That way I could keep the speaker level lower — less spill in the microphone! He's such a master of live performance with a handheld mic that it seemed like the logical way to proceed. With Martin, we changed the setup for each track, for example: an AKG C12 or a Korby KAT47. For the track "The Child Inside" we recorded him in a tiled room. I blended a large diaphragm mic — the Korby, if I recall correctly — with a contact mic that was wrapped around his neck. The contact mic has this muffled, inside-your-head sound, and the room mic is really live and splashy. The idea was to make a disconcerting vocal sound!

Delta Machine was the third album you did with Depeche Mode. It seems they really like your way of working.

Yeah, I hope so! Well, I know what they don't like — which is sitting in a room, looking at the back of somebody's head who's looking at a computer screen. That is really boring. I don't like the creation process being a clinical thing, where we mess around with computers. My experience is that if you have good musicians, every minute you spend editing or quantizing is a waste of time, because you could get them to do it better. We did a lot of that on the last record, where we'd get to a certain stage of a song and I'd say, "You know what? We should start it again. It's going well and it's sounding interesting, but it hasn't got the same spark in it that's really exciting me. What we'll do is we'll do exactly the same song again from scratch, now that we know what it is." It's the same way with a guitar band; when we've got it finished but it's not quite right, we'll play it again. The result is better because you've learned so much about the song, and it's a much more exciting experience. As soon as we felt like it was laboring, we'd stop and start again from scratch. We'd do it in the same key, at the same speed, so everything is interchangeable, and we're not losing anything.

So, with the first try, you basically lay down the arrangement, and then you replay it with all the experiences you've had?

Either that, or we just say, "This is the thing that we really like about this song. Now we're going to completely rework it and just keep that one thing." That was the case with "My Little Universe," from the last album. The demo was really infuriating, because it sounded like an unfinished song that had loads of potential, but we couldn't get it to sound finished. We ended up in Santa Barbara on the last day of the session; the clock was ticking and we had 6 hours. I said, "We'll do '...Universe.' We'll keep the vocal and the click track." [laughs] Dave had done this brilliant vocal. "You have the next 45 minutes to pick a synth." Martin had one, I turned up a drum machine, Christoffer [Berg], our programmer, and Ferg [Peterkin], our engineer, were doing other sequencer parts. They basically had a jam for about 45 minutes on this groove. I just sat back and let them try everything. Dave and I were listening to it, and I was taking notes. I took everything that they'd done, 1800 bars in Pro Tools. There were a couple of noises that they played just right, and there was a 2-bar section that I really loved. [laughs] I collected the bits I really liked, and edited the 2-bar-section around to get rid of anything I didn't like. I built it all from that, with these noises they put in.

But that was some laboring then, instead of the "redo" idea...

I heard what was great and what was bad about it, and it sparked off things in my head. It was one of the things we talked about earlier, about following your inspirations and doing it quick. I was like, "Now that I've listened to it so closely, I know exactly what I want. These two bars are everything I need." I was realizing what I was hearing in my head from what they'd done. Having done that, the result inspired Martin to do some extra parts and flesh out the structure of it.

Does it help to lay down a rule, so the constraints spark something?

You have to do that. Especially in a studio, where you have every option at your fingertips, it's all about limiting the options. Otherwise you'll get hopelessly lost.

Looking back, what was your most difficult project to date as a producer?

I did a record with a band called Clinic called Walking with Thee. It's actually one of the records I'm the proudest of, in a lot of ways. They asked me to do the project, and it was very early in my career. When I walked into the studio, they gave me a booklet they had printed out, which had all the songs listed, as well as the exact arrangements of the songs, to the last bar, with the exact tempo and length. They had a list of all the instruments for each song.

Sounds like they already did the production themselves.

Well, they had a description of how all the instruments should sound. I was like, "Well, what do you want me to do?" They said, "You're just gonna stop us from arguing!" [laughs] It was funny, because — as we were talking earlier about limitations — there were so many limitations on that project. Back then, I was thinking that this wasn't going to be a creative experience for anybody, that it was just going to be recording things and saying, "Yes" or, "No." Actually, it became a really creative experience, because I had such a limit to what I could do within the project. I could find ways to manifest myself. There were certain areas they weren't that interested in, like drum sounds. The more outlandish the drums turned out, the more they liked it. The drum sounds on the record are fantastic! [laughs] I could do what I wanted there. Guitar sounds were very heavily policed. They had a really clear view of what they wanted of the guitar sounds. I was meant for the groove, and the drums, and the bass sounds. I was kind of allowed free reign, which meant I could really impart my vision for the songs. It was very much in the groove area, which was great! I really enjoyed doing that.

For the record Love Your Dum and Mad, by singer/songwriter Nadine Shah, piano and vocals were done in a big warehouse?

Yeah, we recorded all the piano parts in a big curtain superstore in Newcastle, which Nadine's father owned. They'd just moved into a new warehouse, so it was empty when we got there, which was great. I put together a six-piece-band, and we recorded that in my studio in London. We had a PA set up in the room, and we bounced the sound within the room, and then we recorded the room. All the reverb on the album is natural — vocals and everything. I had microphones that were 100 meters away from the piano! When I started recording, my first experience was with classical music. They work on location all the time, so I'd turn up with a van full of equipment and set up a studio. I love doing that! I've got a portable 8-channel Neve desk. That's got direct outs to [feed the computer]. It only works if you have musicians who can deal with it, specifically singers. I don't know many other vocalists that could have cut that. Nadine's vocal performance is of such a quality. When you're dealing with that level of performance, it's very easy — you can use the acoustics.

How did you come up with the idea of creating that landscape?

It was a desire to record it in a way that was using big acoustics. We really wanted it to not be a church; we wanted a colder, harder edge, like a warehouse. All the extra noises — the rattling, traffic noises — give it richness and texture. I amplified those in mixing, where I wanted them. In the song "Winter Reigns" there's a massive rumbling. That is actually me taking off the low-end filter of the room mics and turning the bass up. That's just the ambience! If you record in a clean way, you don't have those things to play with. I find those sorts of things much more creative.