Patrick, how did you end up in this position?

Patrick Kraus: Well, when I was in high school I worked in record stores, like Licorice Pizza. I had enough exposure to label people from that that I knew I wanted to be in this business somehow. Then I had some friends who were in a band and worked in a recording studio. They brought me along and I thought, “I want to do this.”

Paula Salvatore: You were raised in Santa Barbara?

PK: What I would say about Santa Barbara is you can’t wait to get out of there when you’re a kid and then you spend the rest of your life trying to get back. When I was done with school I moved to L.A. and started knocking on doors. I got a gig at a studio making coffee and answering phones.

PS: Was that The Bakery [Recording Studio]?

PK: Yes, The Bakery. Within a month of getting the gig, the guy who was the second engineer was always late. He was late one day a month after I started, and the owner was so pissed. He was talking to the guy on the phone, “Don’t even bother coming in.” He turned to me and said, “Are you ready to jump into the session?” “Yes, I’m in!” I had no idea what I was doing, as usual with these stories, but somehow it all worked out. I spent a few years working at various studios as a second engineer, and then a first engineer, the hours were so crazy. Sometimes you’d go to work on a Thursday afternoon thinking you’d come home that night, but then you’d work all the way through Saturday. After a few years of that I wanted to find something a little bit saner. Pro Tools was starting to come into the world. I never thought in my life I’d have to touch a computer for anything, but I started seeing these guys in sessions running Pro Tools. Remember the days when people didn’t quite trust Pro Tools? So we’d run it at the same time as we’re running the tape, and maybe we’ll use a couple bits and pieces.

PS: Al Schmitt did that a lot at the beginning.

PK: For a while we’d have these sessions and there’d be a guy either in or next to the vocal booth with this computer rig. I wanted to see what that was about. I had lunch with a friend of mine who also worked in the studio world and told him, “I want to do something that’s 9-to-5, in audio, using computers.” She said her husband worked at Warner Bros Records in the mastering department and let me know they were looking for somebody. I went and talked to this guy, and he introduced me to his boss. It was Lee Herschberg. I spent 17 years as a mastering engineer. Things changed and the companies all contracted, so they were like, “Oh, the janitor? You’re the A&R guy now too.” They finally got around to me. “Okay, you’re the audio engineer. Can you put a sentence together? You should manage the studios.” Then I started managing the studios, got the archives, and they gave me production. I ended up as an executive at Warner.

PS: With Lee?

PK: Lee had retired.

PK: I ended up running the digital supply chain at Warner Music. Sony was putting together a business to supply digital supply chain services for the music industry, so they asked me to go over there and help build that business, which I did.

Ursula Kneller: Sony DADC [Sony Digital Audio Disc Corporation]?

PK: DADC. Then my boss there ended up moving over to Universal as the President of Global Operations. He asked me to come over and run studios, productions, and archives.

What year did you start working at Capitol?

PK: I started at Universal a year ago. Of course it’s such a small business that from the moment I walked into the door I kept running into people I’ve known forever. It’s a lot of fun.

Had you been to the Capitol tower before?

PK: I was here in ‘91 for a Beastie Boys party up on the roof for Check Your Head. I don’t think there was anything happening in the studios that night. Then I came again in ‘93, ‘94, ‘95 when all those listening tests were going on with SDMI [Secure Digital Music Initiative]. I remember by then, Capitol Studios already had a fantastic name.

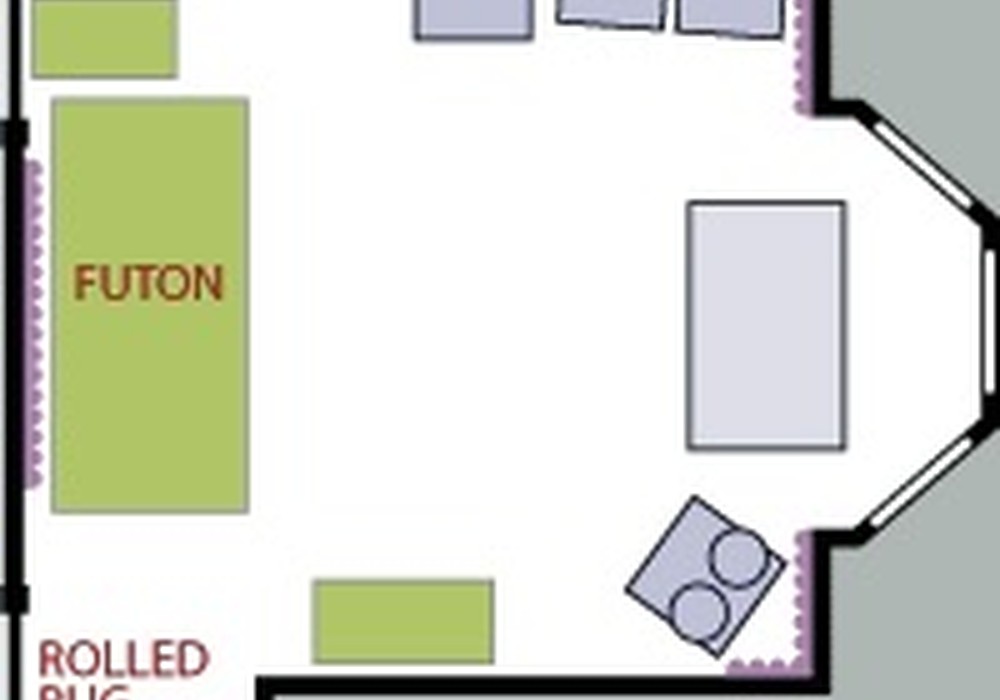

What’s going on in the studio today?

PS: We do a really great philanthropic event every year for the last 26 years. It started with Joe Smith, who’s a sponsor of CalArts College in Valencia. It’s a school program where they come in with ten or twelve bands and do an original song. The teacher, David Roitstein, picks who’s going to be in the bands. They come in every year for two days and track and mix it, and we release a CD.

Is it to get the students familiar with going in and doing a session?

PS: Yes. A couple of the guys who participated are now full-fledged musicians that come in.

UK: One thing we did last year was Maximize Your Mix.

PS: It was to get some kids in the studio to experience what it’s like working with professional engineers, and give them a chance to get hands-on experience.

UK: We worked with UCLA, USC, and Cal State Pomona. 28/Tape Op#114/Ms. Salvatore/(Fin.) We had students from those three schools come in for a two- day seminar. There’s so much knowledge in this building. It wasn’t just the engineers. We got some interest from the A&R folks from the labels too. It was really cool.

You guys seem to put out a lot of fires.

PS: I hate when there’s a fire that I don’t know about.

PK: I’m not overseeing the day-to-day so much. I interact mostly with Paula regarding the strategy of the studio and with Ursula and how we present ourselves to the marketplace, events we can do to raise the profile of the place, highlight the legacy, and those kinds of things. We have to operate in the corporate environment of Universal Music Group, which is a huge company. I interact with people at headquarters. We have sister studios around the company, so we try to find ways to work together and get some efficiencies that way.

Most studios are very independent. This is very different.

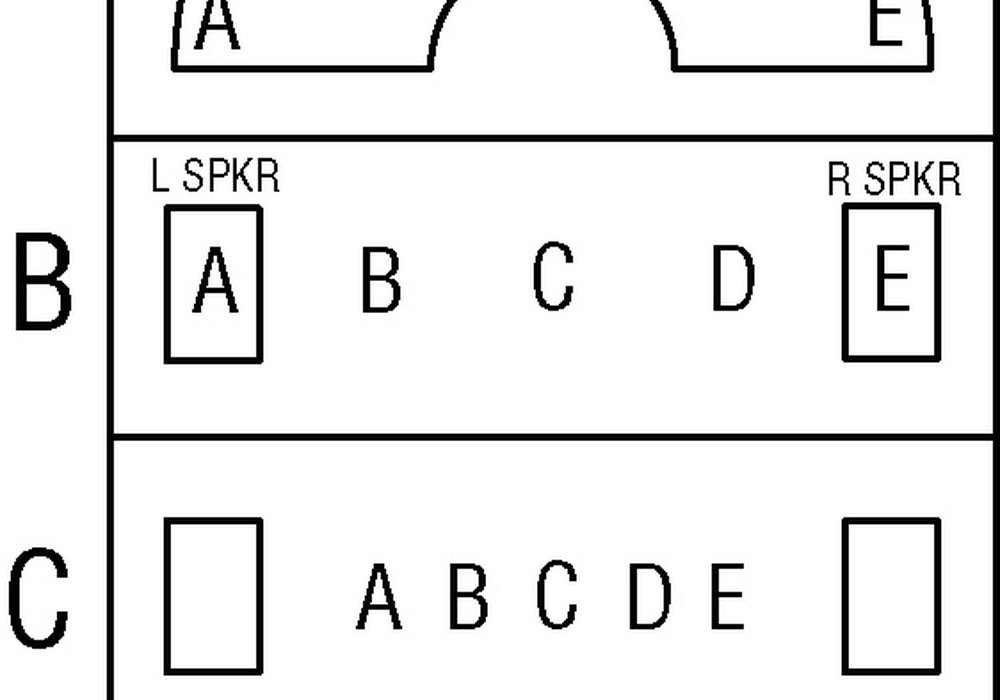

UK: Capitol and Abbey Road are the only two large, label- owned studios left.

PK: There used to be a time when all the recording studios were owned by labels, in New York, Nashville, and L.A. Abbey Road doesn’t really belong to a label. It’s owned by Universal Music Group, but it’s its own business unit, so it’s not really affiliated with a label so to speak. EMI as a label isn’t owned by Capitol or UMG anymore.

PS: EMI always had Abbey Road.

PK: But there’s no RCA Studios. There’s no Sony Studios anymore. They own Battery, but they don’t really run it as a recording and mixing facility. It’s a totally different business now.

PK: But there’s no RCA Studios. There’s no Sony Studios anymore. They own Battery, but they don’t really run it as a recording and mixing facility. It’s a totally different business now.

What kind of tech staff do you have on- site to deal with this?

PS: We have a big tech staff. It has to be almost 24-hours. We have three day guys rotating. One of our techs was so good at mastering vinyl that now he’s doing that 90 percent of the time. We had a lathe in storage so he started putting it together and testing it.

PK: He’s amazing.

PS: Don Was was working on Blue Note releases for the 75th anniversary, and he gave him half of them. He won a mastering shootout.

UK: We have so much vinyl mastering happening now that we had to double our vinyl mastering resources.

PS: That’s one reason we were so excited about the vinyl fair in May.

UK: Exactly. There’s such a focus on vinyl these days. We’re churning them out and the quality is at such a high level.

There’s a wonderful back catalog. Do you take care of archive stuff too?

PK: Yes. We store most of our stuff in the US with Iron Mountain.

I’ve heard about that yeah.

PK: We have probably close to two million assets. In London we have a facility in a part of town called Woolwich. Then we have the old EMI facility in Hayes, where we have historical artifacts going back 1897. Just incredible stuff. Old EMI tape machines, gramophones, there’s a Nobel Peace Prize from one of the scientists who worked or did research in the scientific research department. EMI built the electronics for the royal microphones over the years, so we have a bunch of royal microphones from the ‘30s and ‘40s. All this amazing stuff.

PS: We do baking and restoration too.

Everything needs to be done.

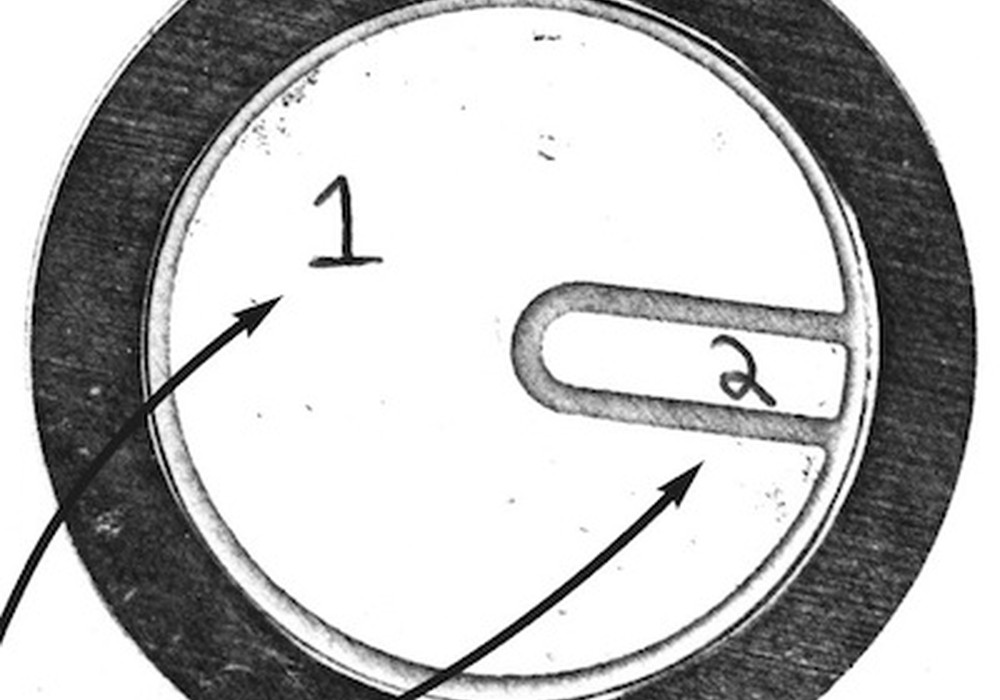

PK: Yeah. I think between the three vaults I was talking about, we probably have four million assets. We’ve been trying to make sure we have everything preserved for future generations. It’s not just digitizing analog tapes. We also look at collections of CD-Rs that we might have as a part of an archive. There might be 150 CD-Rs that have some Sharpie scribbled on it. People who are working in the business now, or who have been in the last 20 years, have a pretty good chance of trying to figure out what’s on those things and what the relevance is. But fast-forward 50 years and people won’t have any idea what to do with these things. We’re trying to get as much information about these assets and preserve them in a way that they’re future-proofed. What’s the difference between rough mixes and final mixes, or the difference between an EQ’d Dolby 1/4- inch tape versus a flat mix on a 1/2-inch tape. That’s the kind of knowledge that over time is going to start to dissipate a little bit.

And as things get digitized sometimes you’re not sure what the source was too.

PK: Right, so we need to be as transparent as possible, and document pictures of the tape boxes. We have situations where years ago somebody might have received a box full of tapes or assets and we didn’t really know what to do with it. They put it in the archive and figured they’d worry about it later. but then So now we’re opening up boxes and finding tremendous assets.