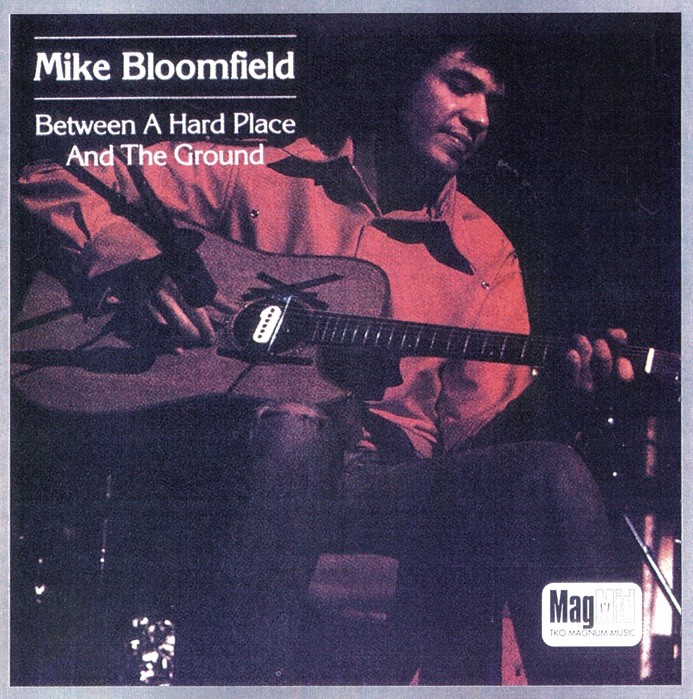

Twenty years after his death, the late Michael Bloomfield still exerts a gravitational pull over anyone who heard his ground-breaking blend of blues- rock guitar power and modal improvisations. That mixture captured my imagination — I can remember trying to kill time on a lengthy high school bus trip, and swapped Cream's Disraeli Gears for Nick Gravenites' My Labors, which had Bloomfield's fingerprints all over it. As I was enjoying "Gypsy Good Time", somebody piped up behind me, "Don't you have any music that isn't bizarre?" Suitably appalled, I turned around, "C'mon, man, this is your heritage! Don't you care where your Top 40 comes from?" I drew a blank stare, but I'd made my point.

Bloomfield's friend, and producer, Norman Dayron, relishes the anecdote. "Michael's idea was [that], you always go back to the source — as far as you can, to the plantation sound, the work song, the prison song. He was not interested in music that was created by imitating what someone else did last week."

Bloomfield practiced what he preached, shunning the major label rat-race after Super Session (1968), the jam-oriented album that became his only gold record. Instead, he focused on playing his San Francisco Bay home-turf, and recorded for small indie labels — making his work hard to find before he died of a drug overdose under murky circumstances in February 1981.

Now, Bloomfield's work is undergoing a reappraisal, after a series of reissue CDs — including Live At The Old Waldorf (1998), which Dayron compiled — and a new, unflinching oral biography, If You Love These Blues (by Jan Mark Wolkin and Bill Keenom: Backbeat/Miller Freeman Books). Dayron is among numerous friends offering insight into Bloomfield's musicological bent, as well as his bouts with insomnia, addictions to heroin, and alcohol — and contrarian quirks that eventually spun out of control (such as blowing out gigs).

Home Recordings For Fun (Not Profit)

Dayron originally planned on becoming a teacher, having left his New York City home at 16 "just to get the hell out of there," he says. Musically, he preferred classical or jazz. "I didn't listen to blues at all," he recalls. "I had a pretty good ear — I'd taken piano and violin as a kid. I was never any good, but I could get by. I knew something about music." At the University of Chicago he met others who shared his new love of the blues: Paul Butterfield, guitarist Elvin Bishop, vocalist Nick Gravenites, harpist Charlie Musselwhite, keyboardist Mark Naftalin... and Michael Bloomfield. "On the South side, on a summer night, there'd be guys sitting on the stoop, playing guitars," Dayron says. "So I saw there was this unique music, and I just started to really like it."

Born in 1943, Bloomfield was sitting in with blues greats like Muddy Waters while still a teenager. Even then, however, his style transcended the idiom — as the brisk acoustic picking of his "Bullet Rag" or the traditional "J.P. Morgan" demonstrates. Both tracks represented "probably the first semi-serious recordings that Michael ever made anywhere," says Dayron, who captured them at his apartment on January 28, 1964. He compiled those tracks for a CD that accompanies

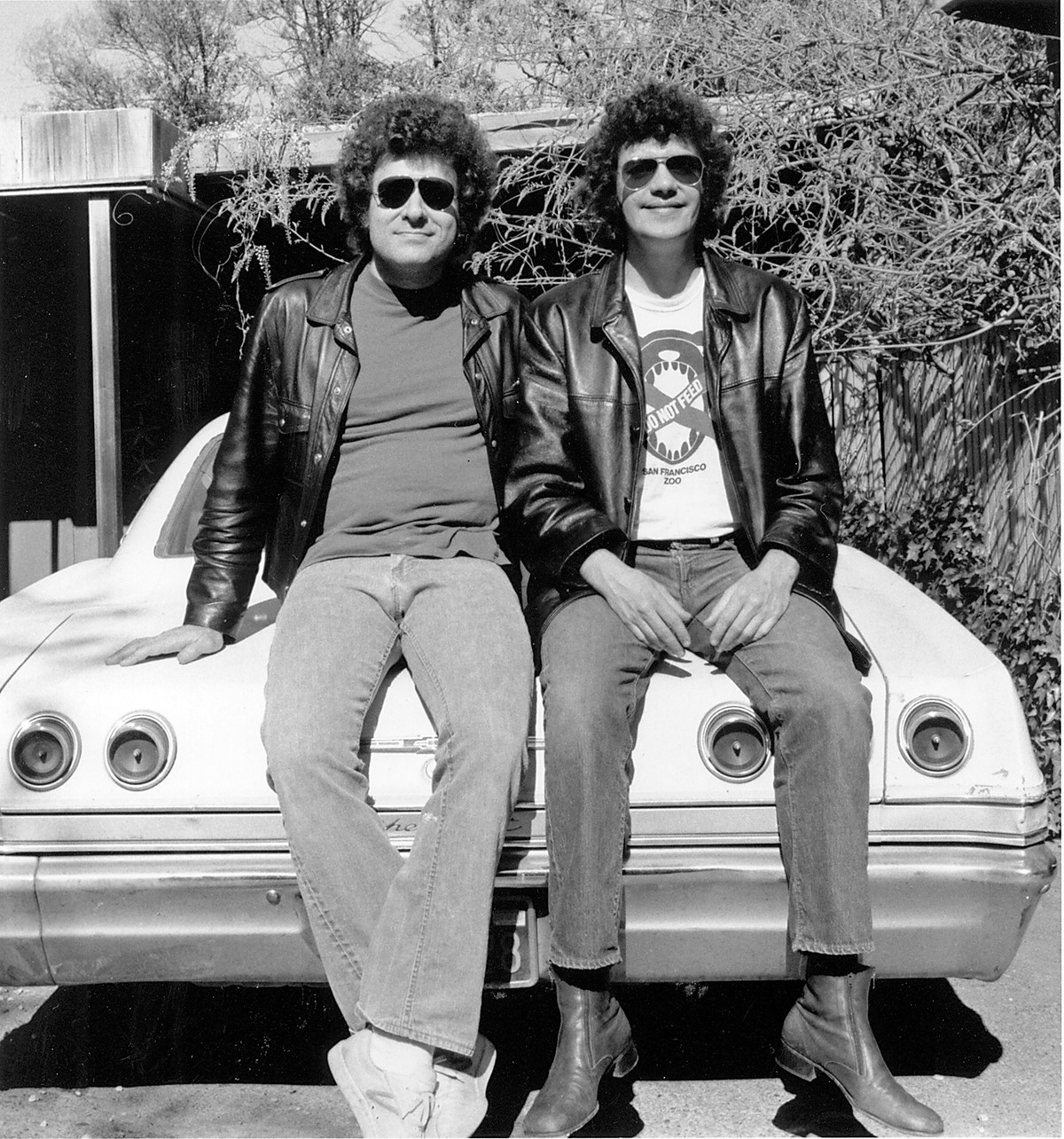

Wolkin's book, and used an Electro-Voice 654 omni- directional mic, and a cardioid 666, "a high-tech lookin' mic, at the time," Dayron recalls. They accomplished Bloomfield's first overdubbing on another track, "Kingpin," by cutting the Tandberg tape recorder's erase head wire. "If you were sensitive to the volume changes, you could overdub in mono — maybe 20 tracks," says Dayron. "It would just record, and record, and eventually stuff would just disappear into the ozone." The CD also showcases some jaw-dropping snapshots of Bloomfield's 21-year-old guitar fury ("Blues For Roy", "Country Boy", and "Gotta Call Susie"), recorded at Big John's on October 15, 1964. Norman used an Ampex 601 recorder with seven-inch reels, and hung a Neumann U-67 mic from a rafter in the room's "sweet spot", which varied, depending on how many people stood in the room. "In some places there'd be a 'suck- out', where the bass would just disappear," says Dayron — then "you'd walk four or five feet over, and all of a sudden, the bass would be there." He then ran a cable to his tape recorder, and taped an Altec mic ("the size of a big salt shaker") to the PA mic, which he separated with a piece of sponge rubber. "Then, I would just mix the vocal with the band," says Dayron. "I'd pick up the whole band sound with the Neumann, and get the vocal with the Altec."

Studio Seasoning (For A Reduced Salary)

Because his University of Chicago scholarship only covered tuition, Dayron took a job cleaning up after sessions at Chicago's legendary blues label, Chess Records. "During the sessions, people would throw up on the recording board," he laughs. By 1965, "for a reduction in salary," Dayron became an apprentice engineer. For "another reduction in salary," he moved to apprentice producer, learning from people like Willie Dixon ("he was like a conductor").

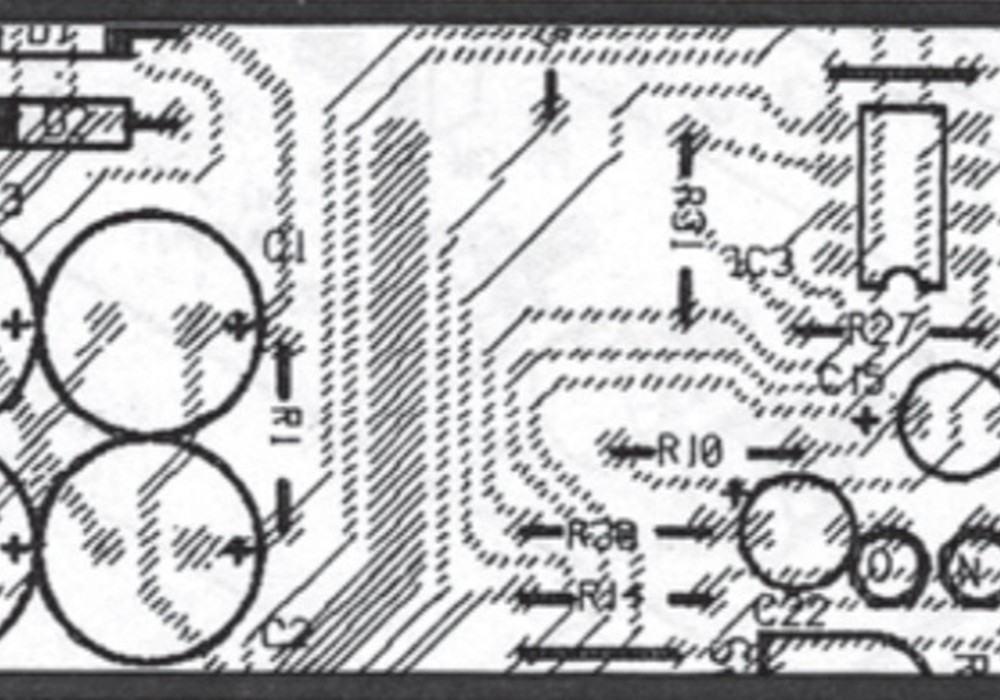

Bloomfield's crisp slide guitar had also made its mark on Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (1965), the modal peaks of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band's East-West and the blues-funk-gospel-rock fusion of the Electric Flag's A Long Time Comin' (1967). Dayron's production debut came on Fathers And Sons (1969), which teamed Bloomfield and Butterfield with the men they considered their mentors: Muddy Waters and his pianist Otis Spann. "We used Chess Studio A. Believe it or not, it had a 12-track Scully recorder, a Neumann console, and Fairchild compressors," recalls Dayron. "They had a lot of the old Pultec tube equalizers."

The album's popularity encouraged another Chess all-star outing, The London Howlin' Wolf Sessions (1970) — with heavyweights like guitarist Eric Clapton, keyboardist Steve Winwood, and the Rolling Stones' rhythm section, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, being used to augment Wolf's raw vocal style. Again, Dayron produced and Glyn Johns [Tape Op #109] engineered. Recording...