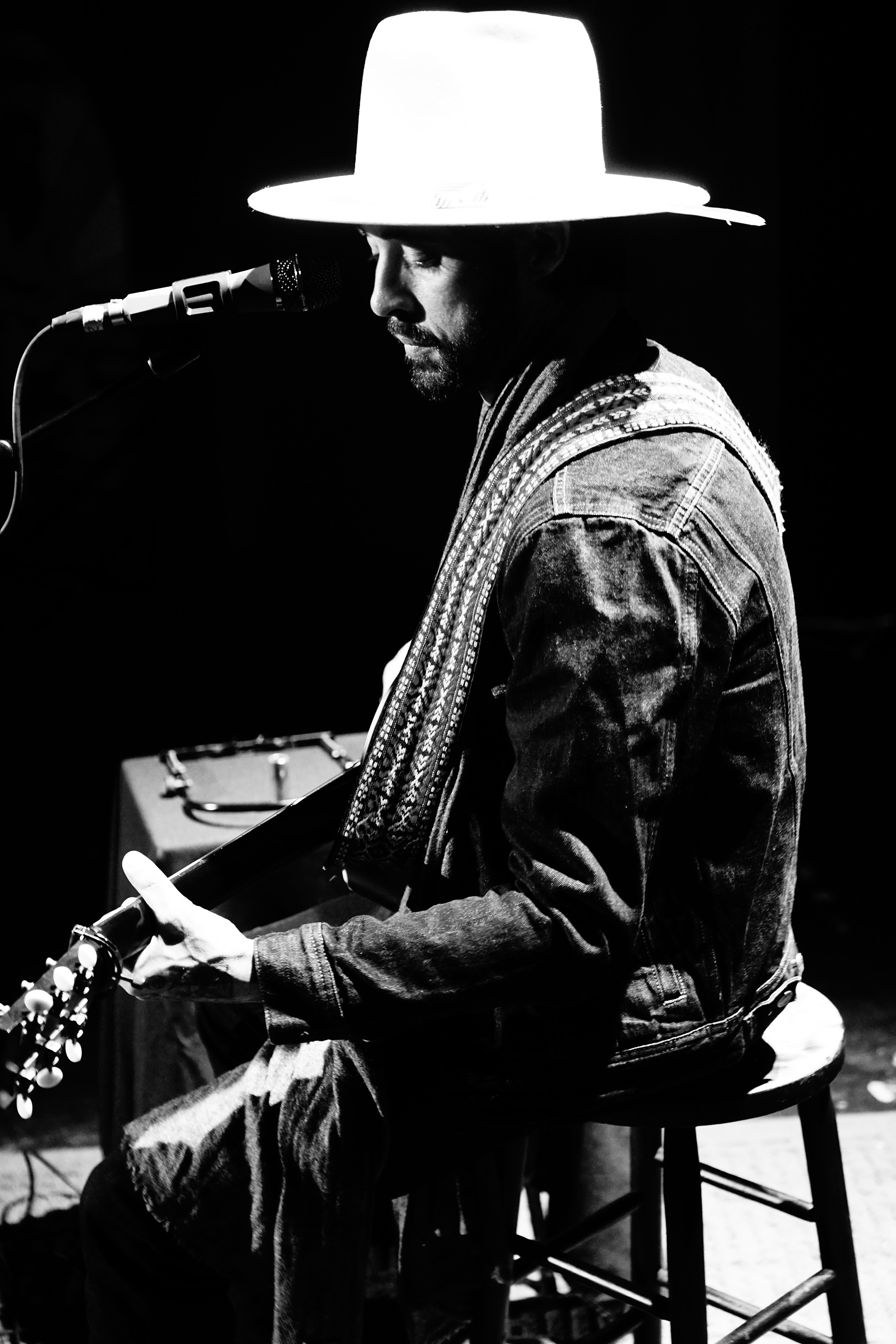

From humble beginnings in Hobbs, New Mexico, and a childhood spent moving from oilfield to oilfield for his father's jobs, Ryan Bingham rode bulls and eventually learned to play a guitar given to him by his mother for his 16th birthday. From a first gig at a biker party, to every roadhouse in the nowhere South, he honed his songwriting and playing, which eventually landed him a deal with [Universal Music Group Nashville's] Lost Highway Records. His big break came appearing in the film Crazy Heart, alongside Jeff Bridges, and his song from the film, "The Weary Kind" earned Bingham an Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, and Critics' Choice Award for Best Song in 2010, as well as a Grammy in 2011. The Americana Music Association also named Bingham 2010's Artist of the Year. Almost a decade on, Ryan is still writing, acting (most recently in the Netflix series Yellowstone), and making great records.

What was the process of making American Love Song, your new album?

It was a bit of a process. I was seeking to work with a producer on this album. I wanted to collaborate with someone on this thing, and it took me a while to zero in on someone to work with. The songs were so personal to me, but, at the same time, I wanted to step out of my comfort zone and not be afraid to go in a different direction if that's what the songs called for. I ultimately ended up calling Charlie Sexton in Austin, Texas, and saying "I want to make a country-blues album, in the vein of Beggars Banquet with Terry Allen-esque themes." The songs are part autobiographical and part fictional. It's a love story that takes place in all the different spots throughout the southwest where I grew up – in Texas and all – and moving my way out to California along those highways and roads. Each song takes place in a different setting. It not only represents where I was living or staying at the time, but the people I was hanging out with, the kind of music I was listening to, the food, and the cultures. There's a lot of different kinds of shit going on in the south, and Texas in general. It's such a big place. All the swing music, country in the south along Louisiana and the coast, the Houston hip-hop scene, Cajun music, and jazz, as well as the Tejano and Conjunto music on the border and in New Mexico and California. It was about documenting that journey.

You've been acting for a while, and your wife, Anna Axster, is a filmmaker. How much of that process has been brought into making records like this one?

I think more than I realize. I've always looked at songs as if I'm looking at an image and describing it. Writing down and describing the images in my head of places I witnessed growing up, or traveling around the world. Weaving the stories into it. It's not only with the songwriting and recording an album as a whole, but also incorporating that into a live performance. I think the acting has come into that. I come on stage and tell my stories in between the songs; what they're about and what they could be about. I went and saw Springsteen on Broadway several months back, and it was such a mind-blowing performance. I've always been a fan of Bruce Springsteen, but after seeing that performance – and how he used his life story and wove that in with the songs – it was really inspiring and something I wanted to explore. Writing new songs and performing them for people, you're really out there telling your story and trying to find ways of getting that across. I appreciate that songs are meant for people to interpret in their own ways, and with their own stories as well. But sometimes songs are interpreted in the wrong way. They're taken out of context, and it might be something completely opposite of what I intended. I think it's nice to be able to explain where the root of where some of that comes from.

Ultimately, as an artist, you cede control. When I first put American Love Song on, I noticed immediately how Stones-y it is.

I've always been into a lot of the Texas guys, like Lightnin' Hopkins and Townes Van Zandt. But really, I fall more on the blues side. I always loved playing acoustic slide guitar, and the way that the Stones played country music. Those records – Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed – where there are fiddles and steel slide guitar, there's that mix of those sounds that I grew up familiar with in different areas of Texas where I was living. I think I always wanted to make this kind of record, but never knew quite how to communicate that. One great thing about working with Charlie was that I didn't really have to explain to him what I was hearing in my head. He was like, "What are you hearing? What do you want to do?" I said, "Man, Lightnin' Hopkins, Terry Allen, Beggars Banquet." He's like, "Oh, yeah; come in."

An important part of collaboration is having those references. You already have a common language. Where did you make the record?

We moved around a bit. Charlie was on tour with Bob Dylan, and back and forth in the studio. We wanted to do everything at Arlyn Studios in Austin, Texas, but it was only available for a certain time. Charlie called up and said, "We can do it right now if we get in there." We did some of it at Public Hi-Fi [Tape Op #27] in Austin as well. We finished it up with my friend Justin Stanley in Los Angeles, but the majority we did there at Arlyn.

How much pre-production time did you get with Charlie Sexton?

I'd been writing songs for the past couple of years. I'd done pretty extensive demos at my house. I actually took some recording gear to a buddy's ranch out in New Mexico. He has this little cabin in the middle of the desert. I had the songs quite far along, as far as certain elements I wanted on them. Whenever I sent those to Charlie, there wasn't really any preproduction. I wanted help with some choruses and arrangements on some of the songs. Even songs that I might have already had a chorus for, or had some bridge or instrumentation on it, I'd take it to him and leave it really bare-bones. I wanted to have his input and for him to express his musical direction when it came to the band and everything. I think we got together for maybe a week and played with guitars and piano. I sent him the demos, so he had time to listen to those songs. We went into the studio, and the band had never heard them before. We sat down; Charlie talked to those guys, and was like, "Let's get it!"

Did you put the band together or did he?

He did. J.J. Johnson [drums] and Scott Nelson [bass] were the rhythm section in Austin. I wanted to leave that up to Charlie. I wanted to put all that into Charlie's hands. For me, it was to be able to focus on the songs and perform them. We tracked a lot of that live, so I didn't want to really have to think about that. My wife and I have our own record label, and I finance my own records. The only part of that which makes me nervous is that I don't always have a ton of money to spend in the studio. I try to get as much work done as I can before I go in so that I can really make the best out of my time. It was definitely a process of having to hold myself back and being like, "Let it go. Let it be what it's going to be." Not to try to plan everything out. I let Charlie take it into whatever direction it was going to go. It really took the songs to places I couldn't take them. The references I had given him – the Rolling Stones, Terry Allen, Lightnin' Hopkins, or the acoustic Texas Blues – I don't necessarily know if I could go in with a band. I don't have the musical knowledge or lingo to be able to communicate that to a band. I'm the guy who started playing guitars at the rodeo on the back of a pickup truck. I don't have any formal training. Charlie could really get in there. He could really communicate all that and make it happen.

What did Charlie bring to the songs that surprised you?

Definitely different grooves. He and J.J. have worked a lot together. He brought this [Roland CR78] that you can program click tracks out of; old-school ‘80s analog. He would come up with these crazy beats to use as a click, and then I would play along to it. What they would bring into it would be completely different, just from the way they were hearing it and what Charlie wanted to get. I really found it interesting, and a lot of fun, to be around that.

How do you capture demos, and what's your home studio like these days?

I have one of those Tascam 8-track reel-to-reels and a board, but for all of the demoing I was doing I was using Pro Tools and a little laptop. I brought two or three guitars, a mandolin, and a keyboard, and did all the demos on that. I kept it very bare bones and minimal.

How many tunes did you present to Charlie?

I think maybe 16 or 17. I think I had 30 or more, altogether. I've got enough [leftover] that I want to do another album, but acoustic solo. It's a lot of ballads. I had a pretty clear idea of what I wanted on this album, and then on the next one.

You've worked with a bunch of producers over the years. I wanted to read you a few names. What about T Bone Burnett [Tape Op #67], who you worked on Junky Star with. Did that collaboration come out of the film, Crazy Heart? [T Bone produced the soundtrack]

That whole experience was such a trip for me. It all came through that film. It's one of those things you can never really be prepared for; I wish I had been a little bit older and experienced when I got into that situation. I was working on the soundtrack with all the musicians that played on that, sitting in a room with my heroes; people I heard play on records for decades. Now I was sitting in a recording studio and they're playing my songs. It was pretty magical and surreal. To continue on and get to do another album with T Bone, I don't know. I still feel like I was not really able to soak it in so much. It was all happening so fast. We recorded that album, Junky Star, in five days. First, we went to T Bone's house; me and my band. We sat down in the living room and he said, "Play them all for me. I want to hear what they all sound like when you're playing them live." We played them for him, and he said, "We're going to record them like that." We went over to The Village, set up, and did one song right after the other. Probably two or three takes of each song, and that was it.

Wow.

At the time I had my long-time buddies, The Dead Horses, that had been in my band forever. We had a couple of records out, and then the movie hit. After that, I got all the pressure from my manager, and even from T Bone. They wanted me to do the next record with their guys. I wanted to too; the opportunity to do a record like that with all those players. It would have really broken the hearts of all those guys in my band if I had shrugged them off and said, "I'm going to do this right now." I remember talking to T Bone. We went out for dinner. T Bone said, "I think we should use these guys for the record, and it's going to be amazing." I said, "I hear you, all the way; but I can't do this to my guys right now, at this moment. It's going to have to be a longer process." He's like, "All right, let's get in there and get it how we can get it." None of us were session players. We were young kids who played in bars and honky-tonks. Not to say we didn't have a vibe. There was something special going on between us when we played; but there's a difference between some of the players that T Bone has on records, versus guys like me and my band at that time.

Whether you downplay it or not, you guys had a thing going.

We definitely did. I'm not trying to downplay it at all. But I was a young guy at those crossroads.

How about Marc Ford? You did Mescalito and Roadhouse Sun with him.

It was just me and my drummer. We were a two-piece band. I was a huge Black Crowes fan and so was my drummer. I think that was right when Marc had got back with them and started to tour. We were pretty stoked to work with him. He really taught me how to play music with a band. I'd never played with a band; I'd only played with a drummer before. I had a handful of songs, but I didn't know a whole lot about arrangements, or playing with the band and all this space and timing. He was teaching me how to count the song off. That basic of shit. He even went on the road with us for a bit and played guitar. I'd never played electric guitar. I didn't even know how to set it up on stage. He bought me this old Kraftsman guitar for $100 off eBay, gave me a slide, and put acoustic strings on it for me. He got me some little boutique amp with a 10-inch speaker that had two knobs. He said, "You can't get into too much trouble with this! Turn it all the way up and play." He really cultivated things for me, probably more than anybody else. I really had no idea what I was doing out there. I was a kid with a guitar and a handful of ballads. He was teaching us how to play rock ‘n' roll.

How about Jim Scott [Tape Op #75]?

Jim's great. I'd been a fan of his work. I knew he lived in Los Angeles, but I didn't know how accessible of a guy he might be to get in touch with. I don't know where I got his number, but I got his phone number from someone, a called him up, and asked if he'd be interested in working. He said, "Hell yeah. Come out to my place." He's got a studio in Castaic Lake, [California]. It's a big fucking warehouse that he's been collecting gear in for 30 years.

Gear and tie-dyes!

All kinds of cool shit. He's a great guy. I had an amazing time working with him. He's another guy where you can reference a sound, record, instrument, or anything, and he'll know how to get the sound immediately. It doesn't take him half an hour to get a mic set up. He turns it on, and there it is.

I think that's a huge part of production; keeping the wheels going.

Yeah. We did Fear and Saturday Night fairly quickly. We tracked two or three songs a day, pretty much live. We did that whole record in a week or two. We could roll on to the next. If something wasn't working, he'd say, "Hold on, guys! I want to change the sound of this over here." You wouldn't even notice him doing it, but a month later – when you're listening to the record – it's like, "Oh, damn!" I could tell where he was making those moves.